Today, the visitor to the city of Rome can visit the ancient Coliseum. The mere sight of the gigantic structure is enough to cast a chill upon the stoutest heart. Its massive structure fills the sky, but the skeleton that exists today is only a shadow of what the ancient Coliseum was in its days of glory, or perhaps we should call it the days of shame. Every visitor to the spot should pause and ponder that open area of ground in the center of the arena, for the blood of many martyrs hallows that small bit of ground. The soil of that sacred spot must be very rich indeed, for much blood has drained into that sand over several centuries.

The Coliseum was known all over the world as the center and climax of Roman entertainment. The Roman masses had an insatiable appetite for observing bloodshed. Gladiatorial games were held there in the arena. Gladiators would be trained for years to the height of physical strength. Then, on the climactic day, they would march out into the arena, stripped naked to the waist. They would be armed with their favorite weapons and would march to the box where the Caesar sat. Lifting their swords or battle axes or spears to the skies, they would chant, “Ave, Caesar, morituri te salutant!” “Hail, Caesar, those about to die salute thee!”

Then the ferocious combats would begin. When one of the gladiators had wounded his adversary severely and the wounded man was lying helplessly on the ground, the triumphant gladiator would look up at the faces in the crowd, and he would shout, “Hoc habet!” “He has it.”

The crowd would then express their will. If they gave the sign of thumbs up, the wounded gladiator would be dragged bleeding from the arena, to recover if possible. If the sign of thumbs down was given, however, the victorious gladiator would lift his weapon to give the final stroke. The crowd would shout in delight, “Recipe ferrum!” “Receive the steel!” The lifeless form would soon lie on the sand, another victim to Roman butchery. Thus the games continued, century after century. Victorious gladiators became folk heroes, the Roman version of superstars or sports heroes.

But these gladiatorial games were not the worst aspect of the Coliseum, for here, pious Christians were slain by the droves. Wild beasts such as lions, tigers, leopards, and bears were kept in pits till they were crazed with hunger. Then they were released upon Christians—boys and girls, old men and matrons, it mattered not. All were made to feel the pain. Sometimes Christians were soaked in oil then lit on fire as if they were living torches. Men and women were torn with iron hooks, grilled on irons, sawed asunder, and placed in boiling pots of oil. Other things too horrible to even speak of were practiced upon pious young ladies. Yet even small children met these tortures with fixed resolution, and many times, the song of hymns would waft up from the blood-soaked floor of the Coliseum, the joyful song of human voices rising above even the roar of lions as the souls of the slain, one by one, rose from the arena to ascend to their Saviour and King Who, as He had done to receive Stephen, advanced to the portals of heaven to meet His martyrs. Roman ingenuity knew no bounds, and every imaginable form of torture, mayhem, and brutal lust was practiced upon the pious Christians of the first through the fourth centuries.

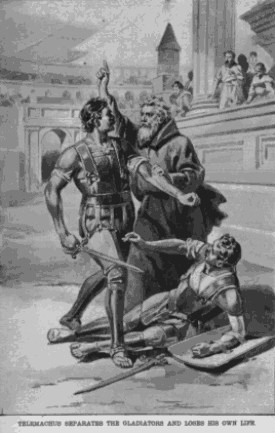

One day, however, at the height of the gladiatorial games, during a celebration of the Roman victory over the Goths about A. D. 370, a lone figure interrupted the proceedings. Without warning, a rough and weather-beaten man jumped over the wall and into the arena. Shouts of excitement over the combat gave way to a profound silence, as all eyes turned from the gladiators to look at the lone figure.

He was covered with a mantle. He had come all the way from Asia to Rome. He was a Christian. He had heard about these barbaric entertainments, and, by the grace of God, he intended to stop them. He had shoved his way to the edge of the arena and jumped into the midst where every eye could see him. He advanced to the two gladiators who were engaged in mortal combat. Interposing himself between the combatants, he faced the crowd. Fearlessly, this hero raised his voice. “In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, King of Kings and Lord of Lords, I command these wicked games to cease. Do not requite God’s mercy by shedding innocent blood.”

A shout of defiance met the voice of our hero. Pieces of fruit, stones, daggers, and other missiles were hurled down from the stands. One of the gladiators, expecting the applause of the crowd, stepped forward and rammed his battle axe into the skull of the man who had dared interfere with Rome’s favorite entertainment. As the hero sunk lifeless to the ground, the angry cries of the crowd died away into a profound silence in the arena. As the life’s blood of this new martyr joined the blood of the thousands who had bled there before him, the crowd suddenly faced a courage that was greater than the strongest gladiator. The work of this Christian was accomplished. His name was Telemachus. From the hour of his martyrdom, the gladiatorial games ceased. According to John Foxe, in his famous book of martyrs, “From the day Telemachus fell dead in the Coliseum, no other fight of gladiators was ever held there.” Such was the legacy of a man who dared to jump over a wall and declare that an aspect of popular cultural entertainment was ungodly and unlawful.

How many pagan entertainments and even supposed “Christian” substitutes of our day await such a display of boldness? It is interesting that Telemachus did not suggest a “Christian” gladiatorial contest to be staged in the Coliseum. It is remarkable that he did not advertise a “Christian play” to be performed down the street as an alternative to the impure productions in the Roman theatre. He did not try to innovate some new strategy to appease the circus-loving crowds of Rome. He did not try to invent a “Christian version” of the circus. God had ordained to save the unbeliever by the foolishness of preaching, not by the clever drama of the stage or the entertainment of the circus.

Telemachus believed, in his generation, that the Bible was sufficient for all faith and practice, that God had ordained preaching as His sole mandated method, and that the way to take dominion over some things was to destroy them and not to attempt to make a “Christian” substitute. The dominion of Christ must be in terms of His law, and He will not have in that dominion anything foreign to that law. Thus, the dominion mandate is lawfully extended over only those institutions that are themselves lawful. Telemachus called for the end of the games, not for the re-Christianizing of them. There could not be a “Christian” circus or a “Christian” theatre or a “Christian” gymnasium. This was affirmed by such men as William Farel, John Calvin, and Robert Lewis Dabney who, following the example of Telemachus, wrote in their own generations against the fallacious notions of “Christian theater,” “Christian dancing,” and “Christian novels.” Sadly today, many Christians are trying to Christianize their own interests and pleasures in the name of “dominion” when, at the core, the institutions they seek to take dominion over are not authorized in the Word of God as legitimate means by which to advance Christ’s Kingdom.

For this truth, Telemachus was willing to jump over the wall and shed his very life’s blood. He had the boldness to command, in the name of Jesus Christ, that the gladiatorial games cease, and by the grace of God, they did cease. Today, the Coliseum stands in ruins while the Church of Jesus Christ continues to advance. But we must not rest upon the laurels of “mighty men” of the past such as Telemachus or Farel or Dabney. Today, in our generation, there are things in our culture, things that are considered culturally acceptable by many sincere Christians, that await the steadfast courage of a Telemachus.

Bibliography:

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs by John Foxe

Discussions by R. L. Dabney, vol. 2

You defile the memory of St. Telemachus by comparing him with heretics and schismatics who dismembered the Body of Christ. Everyone who forms factions in the Body of Christ or teaches doctrine unknown to our fathers is a liar, a thief and a murderer, just like his father, the Devil. “Unless you eat of the Flesh of the Son of Man and drink of His Blood, you have no life within you.”

Mr. Patton,

I am a former cathoholic who was deceived by FALSE TEACHINGS just like you!

Tell me, if I joined a man-made religion and they removed the ORIGINAL 2nd Commandment given to Moses on Mt Sinaia (Exodus Chapter 20) because they did not like it and they liked the money they made building statues and the like, would you think it was good? See Boof of Revelation 22: 12-21!!!!

You Andrew Joseph Patton ARE GUILTY of believing and practicing a lie!

I believe the previous two responders completely missed the point of your post. Telemachus stood up for what was right, and because he did so, the needless shedding of blood was halted in the Roman Colosseum! The evil practices that happened in the Colosseum were put to an end because of the name of Jesus. Jesus worked through Telemachus, and we should allow Him to work through us in that way also. Our world needs more men with conviction and faith like Telemachus!

Way to go!