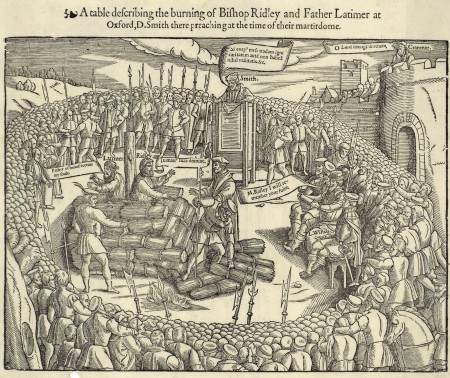

Two men stood back to back at the stake. As a large crowd watched, a heavy chain was passed around their waists to hold them fast. A fagot was kindled. At the sight of the flame, the older of the two men gave utterance to the noblest and shortest sermon he ever gave in his long life of preaching. “Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as I trust shall never be put out.”

These lines have become among the most famous lines in English church history. The chain that bound Latimer and Ridley together on that morning of October 16, 1555, has continued to bind them together in the common mind. Today, it is almost impossible to think of Latimer without also thinking of Ridley. But in these next two issues of the Mighty Men Herald, we will try to consider these men as individuals and appreciate more fully the steps by which they arrived to be chained together at the martyr’s stake.

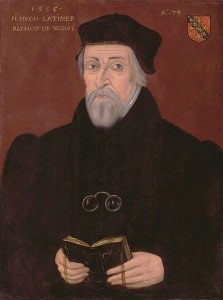

The elder of the two men was Hugh Latimer. He was seventy years old when he was burned alive as a martyr of the Gospel. Latimer’s life was already well spent, and “Old Father Latimer,” as he was known, had already lit a candle in England that would never go out.

Hugh Latimer was born in 1485 in Leicestershire. He was the son of a yeoman farmer and was trained to work the land as a boy. Therefore, he always loved gardens and orchards, and even as Bishop of Worchester, he had a love for plants. He was also trained at an early age to use the longbow, and he became an expert archer. When Latimer was 14 years old, his father sent him to Cambridge University. He excelled in the classics and in the scholastic doctors of the Medieval Church. As true of many schoolmen, Latimer continued his scholastic life after graduation, teaching at Clare Hall at Cambridge. In 1514, at the age of thirty, Hugh Latimer received his degree of Master of Arts. He gained many high academic honors and was also ordained a priest in the church of Rome.

In 1522, the new teachings of Luther began to make their way across the English Channel. Thomas Bilney, a student at Cambridge, smuggled a Greek New Testament into his study room and began to read the Word of God at its source. In opposition to Bilney and the other Reformers, Latimer became the spokesman for the Medieval Church in the debates that arose over the “New Learning.” Latimer openly attacked Luther and Melanchthon and argued against learning the original languages and translating the Word of God into the common tongue.

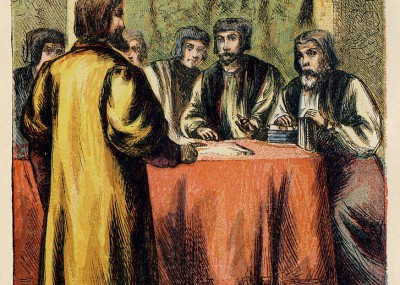

One day, Thomas Bilney went to Latimer’s study and asked the esteemed teacher if he would be willing to hear his confession. Latimer assumed that the young student would confess his heresies and return as a penitent to the bosom of Rome. But Bilney’s “confession” turned out to be his confession of faith in Christ alone and how he had received pardon through the blood of Jesus. The heart of Latimer was pierced by the arrow of divine Truth. D’Aubigne compares the conversion of Latimer to the conversion of Saul of Tarsus. The zealous persecutor now became the zealous preacher of the Gospel. All the learning, the zeal, and the eloquence that Latimer had used for the Pope he now used for Jesus Christ.

Latimer became a bold and zealous defender of truth. He astonished all of Cambridge when he spoke out openly against the Roman doctrine of purgatory. This sermon was followed up by an attack on the immaculacy of the Virgin Mary. Soon, he began to attack the veneration of relics and the images of the saints. During the Christmas season of 1529 he openly attacked the ceremonial trappings of Christmas, and called on all Christians to reject the man-made traditions and festivals of Rome. Latimer probably would have become a martyr much earlier had not the political turmoil over the marriage and divorce of King Henry VIII distracted the realm from doctrinal matters and brought about the downfall of Papal dominion in England. By 1531, Latimer was recognized as one of the boldest and most eloquent preachers in the Reformed party. He became a close friend of Thomas Cranmer, who often warned Latimer to temper his zeal with caution.

Anne Boleyn, the young queen of England, was a firm Protestant and loved the simple preaching of the Bible. She had great respect for the bold preaching of Hugh Latimer and asked Henry VIII to make Latimer her chaplain at court. Latimer accepted this position and preached often before the king and queen. On one occasion, when Henry VIII had seized an abbey and used it to stable his horses, Latimer had the audacity to preach a sermon that kings should not multiply horses. He looked right at King Henry VIII and declared, “A prince ought not to prefer his horses above poor men.” D’Aubigne recounts that there was dead silence in the room, and nobody dared even to look at the king. After the sermon, Latimer’s friends warned him that he might be headed for the Tower. A few days later, the king questioned Latimer about his sermon. Latimer bowed respectfully and said, “Would you have me preach nothing concerning a king in the king’s sermon?” Henry VIII liked this boldness, and though he did not agree with Latimer’s doctrine, he admired Latimer’s courage and he never made a move to arrest him.

When Anne Boleyn fell out of favor, Latimer left London, but he was elevated by Henry VIII to become Bishop of Worchester, where he served for years as a pastor to his flock. During these years, the religious moods of England swayed with the changing wives of the King, but “Old Father Latimer” maintained a consistent loyalty to the simple Gospel he loved and preached.

In 1539, a storm of controversy erupted concerning the hated “Six Articles.” These articles made it clear that Henry VIII, while he was separated from the Pope, was not about to embrace Reformed doctrine. The articles affirmed the Real Presence in the Eucharist, enforced the celibacy of priests and monks, granted the privilege of Papist clergy to hold private masses, and retained much of the doctrine of the Roman church. When the “Six Articles Act” passed the House of Lords, Bishop Latimer renounced his bishopric and resigned his charge. Weaker men like Thomas Cranmer, though they opposed the Six Articles, did not openly oppose them and thus retained their positions. Latimer would not compromise, and he was soon arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London. He remained there in the Tower eight long years.

In 1547, Henry VIII died and Edward VI was crowned King of England. This coronation was a great victory for the Reformed Party. Hugh Latimer was sixty-two years old at this time, and Edward VI promptly released “Old Father Latimer” from the Tower. For the next five years, Latimer preached, taught, and wrote. These were years of triumph for the Reformers of England, but “Old Father Latimer” was very prophetic in his warnings that another violent religious storm was on the horizon. The old man would sometimes say, “Smithfield has often groaned for me.” Smithfield was the place of public execution.

When Edward VI died in 1553, “Bloody Mary” Tudor came to the throne of England. Immediately, she sought to undo all that the good Edward had done. Stephen Gardiner, the queen’s favorite bishop, a devout Romanist and Papist, brought charges against Latimer, and the old man was summoned to Oxford to answer for his “heresies.” For many long months, he and other Reformed churchmen like Nicholas Ridley and Thomas Cranmer were summoned to disputation after disputation. Cranmer, always timid, recanted for a time and tried to blend in with the current system. But “Old Father Latimer” would not compromise. Latimer was so sick that he could sometimes hardly stand on his feet during these disputations. His memory was gone, and his sharp skills as an eloquent orator had faded with the years. But Latimer carried his New Testament with him, and did his best to answer all questions in the simple words of Scripture.

On the morning of October 16, 1555, the entire town of Oxford was in the streets. The younger Bishop Ridley appeared first and looked earnestly for Latimer. Finally the old man appeared and Ridley cried out, “Oh, be ye there?” “Yea,” answered Latimer, “as fast as I can follow.” The two men embraced each other fondly and knelt together by the stake. Onlookers tried to hear their words, but their words of sweet fellowship were lost to this world as they prepared for a better. After they were chained to the stake, the burning fagot was lit and applied to the pile. “Old Father Latimer” turned to Ridley to encourage his young friend, “Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as I trust shall never be put out.”

In a few short minutes, “Old Father Latimer” was in the presence of his Lord and Master. We shall see in the next issue how Master Ridley did indeed play the man in the harsher ordeal that awaited him.

Bibliography

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs by John Foxe

Masters of the English Reformation by Marcus Loane

The History of the Reformation by J. H. Merle D’Aubigne