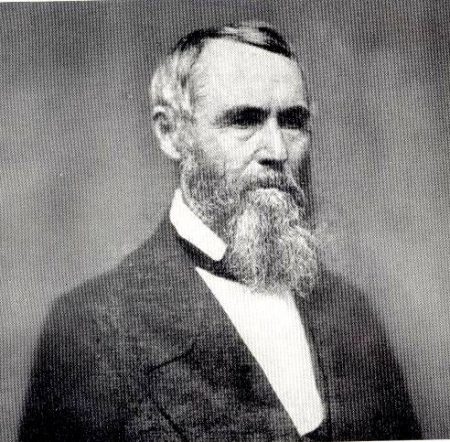

On December 9, 1833, a young Presbyterian pastor named Daniel Lindley offered his services to the American Board of Foreign Missions. He wrote, “I am willing from love to the Savior to make every sacrifice that my going will cost me.” Daniel Lindley was born at Ten Mile Creek in Pennsylvania on August 24, 1801. He came from a long line of pioneers who had been among the first to settle the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. Daniel was educated at Ohio University and then attended Union Theological Seminary in Prince Edward County, Virginia. This theological school, located on the campus of Hampden-Sydney College, was the same institution that produced Robert Lewis Dabney.

After graduation, Daniel Lindley pastored a church in North Carolina for several years before becoming convinced that it was his duty to advance the Gospel of Jesus Christ in the “Dark Continent” of Africa. At the time that Lindley offered his services to the American Board of Foreign Missions, David Livingstone had not yet set foot on the African Continent, and the vast interior of Africa was still a blank spot on the map.

Daniel did not propose to go to Africa alone. In November of 1834, he married Miss Lucy Allen, and the new bride announced her willingness to accompany her husband to Africa. Many claimed that it was a shame to send such a “handsome couple” to waste their lives overseas in the Dark Continent. But God has always seen fit to select his choicest vessels for missionary service. It was the very best of the Christians in Antioch, Paul and Barnabas, whom God chose to send on the first missionary journey.

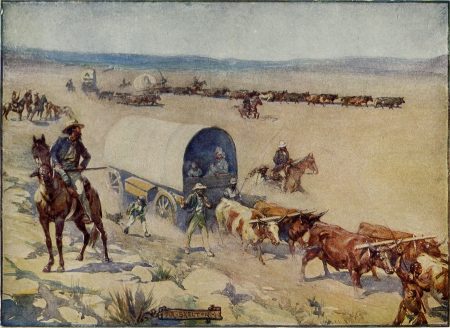

So it was that Daniel and Lucy, only a month after their marriage, embarked on the Burlington in the company of five other missionary couples. Upon their arrival in Africa, Daniel and Lucy were chosen to be part of the Interior Party. This meant that after their long voyage by sea, they were expected to travel 1,000 miles inland by ox-wagon.

Leaving the Cape Colony, they embarked upon their arduous adventure. Along the way they met swollen rivers, malarial swamps, dry wastelands, lions, angry elephants, and the threats of warring tribes. Along the way, in the uncomfortable surroundings of an ox wagon, Lucy Lindley gave birth to a daughter, the first of eleven children that she would bring into the world. She did not flinch at the challenge of giving birth far from the comforts of civilization. Indeed, Mrs. Lucy Lindley has been called “one of the pluckiest women to ever tread the soil of Africa.”

The Lindleys intended to set up their missionary work among the Matabele of King Mzilikazi. At this time, war between various African chieftains made work among the tribes very dangerous. A potentate named Shaka had united numerous tribes under his leadership several years before the Lindleys arrived in Africa. They became the Zulu Confederation. With his highly trained warriors who wielded their assegais, Shaka had swept through south Africa bringing blood and terror wherever he went. After the death of Shaka, various petty rulers like Dingane and Mzilikazi tried to maintain the same position that Shaka had occupied, and bloody tribal wars erupted.

To add to this state of affairs, the Voortrekkers, Dutch colonists also known as the Boers or Afrikaners from the Cape, were leaving the confining regulations of British colonial rule to seek land and cattle in the interior. These courageous pioneers carried with them their Bibles and their vast herds of cattle. They took their large families with them and travelled by ox-wagon into the vast interior to find ample pasturage for their flocks and herds. Although the Voortrekkers carried their Bibles with them, and professed the ancient faith of their Dutch and Huguenot ancestors, they were without pastors or any formal church organization. Their children were unbaptized, their ways were rough, and they saw their mission more similar to that of Joshua and his conquest of Canaan than of Paul and his missionary journeys.

It was inevitable that conflict between the Voortrekkers and the Zulus would come – and it did. Disputes over cattle thefts, water, and grazing land arose between the colonists and the natives. Raids by the Zulu impis and reprisals by Boer commandos escalated. At the “Battle of Blood River” 464 Voortrekkers repelled the attack of 15,000 Zulu warriors and won a great victory, killing 3,000 Zulus without losing a single man.

It became obvious to Daniel Lindley that the Boers needed to be Christianized before the Zulus could be reached with the Gospel. The Boers were sincere believers in the God of the Bible, but they needed the discipline of Christ and the oversight of a pastor they could trust.

Most “ministers” were too weak and too pietistic to be of any use to the bearded Voortrekkers. They had asked for pastors from the Cape, but none had been willing to come and brave the dangers and trials of the African interior. Daniel Lindley was not afraid. In 1839, he opened a school for the Boer children and began teaching them to read and write. Among the young men that came under his Bible teaching was a young farm boy named Paul Kruger, destined to have an important role as the leader of his people in South Africa.

Daniel Lindley worked among the Boers for ten years: preaching, teaching, travelling to isolated farms to baptize children, solemnize marriages, conduct funerals, and encourage the Boers in the ways of Christ. They found Daniel Lindley to be a man after their own heart. He was not a “tenderfoot” like other ministers they knew. He was an American, not an Englishman. He could talk with them about wagons and oxen. He could hitch up a wagon as well as any Boer trekker. He was a crack shot with a rifle, and knew how to hunt the rhinoceros and the elephant. Faced with a line of horses, he could pick out the best and strongest horse, “almost as well as a Boer” – which was the best compliment they could bestow! He was strong, manly, courageous, and a brave pioneer like themselves. He wore a beard like a Boer, rode a horse like Boer, and hunted like a Boer. The Boers came to respect and love their pastor and all that he taught them from the Bible.

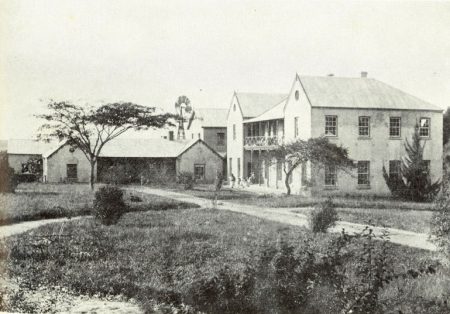

After serving the Boer farmers for ten years as a travelling preacher, Daniel Lindley entrusted them into the care of their own pastors – whom he had helped to train. He turned his attention back to the Zulus. He built a mission station at Inanda, doing his best to help the Zulus learn to manage their land, learn a written language, and come to the light of the Gospel. He met with steady success.

Lucy Lindley founded a school for girls, teaching young Zulu women how to be faithful wives and mothers, how to raise their children in the ways of God, how to cook, sew, and wash clothing. The Lindleys raised their eleven children in the heart of Africa, providing in their own happy and warm family circle an example of what a Christian family ought to be.

In October of 1859, the Lindleys returned to America for their first visit home – just before the brink of the War Between the States. They were grieved to find their land so divided, and they had family on both sides of the growing conflict. One of the Lindley sons served in the Union Cavalry, but one of Lindley’s dear friends was Pastor Robert Morrison, the father-in-law of Stonewall Jackson.

In 1862, they returned to Africa to continue their work among the Zulus. One of the highlights of the life of Daniel Lindley was the day that he ordained the first Zulu Christian to t he work of the Gospel Ministry. Old age eventually forced the Lindleys to return permanently to the United States in 1874, but several of their children stayed in Africa to carry forward the advance of the Gospel. His mission station at Inanda, destroyed by fire but rebuilt again by his own hands, still stands. Zulus as well as Boers still treasure his memory, and there is a town in South Africa today that bears his name.

By the time that Daniel Lindley died at the age of 80, Zulu churches were under the leadership of Zulu pastors preaching the Gospel and singing hymns in the Zulu language. These Christians took up an offering and sent it to America to “bury our father.” This is the legacy of Daniel Lindley. There is much that is bad and ugly in the history of South Africa, but whatever is good and beautiful can be traced in large measure to the sacrificial labors of Daniel and Lucy Lindley.