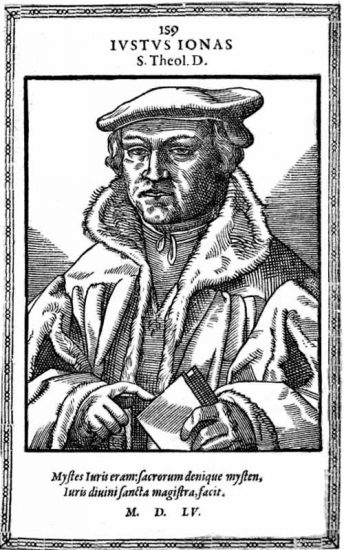

Martin Luther was dying. It was late February 1546. Beside the bed of Luther sat one of his most faithful and loyal friends. Justus Jonas was his name. Luther had spent the last three weeks of his life in the fellowship of Justus Jonas and his family. Jonas and Luther shared similar backgrounds, and Jonas had been a friend and admirer of Luther since 1519. Both had studied law. Both had become disgusted with the immorality and pride of the Roman church. Both had profited from the writing and scholarship of Erasmus. Both had married wives named Katharine. While Luther labored in the city of Wittenberg, Jonas had labored to reform the nearby city of Halle.

The two men had labored side by side in the vineyard of the Lord for almost 30 years. Jonas had a great skill with words, and Luther said that the “elegant and brilliant style” of Jonas did much to help his own “barbaric and unrefined language.” The finished works that Luther published show a blend of Luther’s boldness and Jonas’ elegance. When Luther stood before the Emperor at the Diet of Worms, Justus Jonas was one of the very few men who stood beside him on that tumultuous occasion when Luther defied the Pope, the Councils, and the Emperor and took his stand upon the Word of God.

Now, Luther’s life was at an end. It was Jonas who was at his side when Dr. Luther breathed his last, quoting the words of the Psalm, “Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit. Thou hast redeemed me, God of Truth.” It was Dr. Jonas who preached Luther’s funeral sermon in the city of Eisleben, where Luther died. Jonas chose as his text I Thessalonians 4:13, “But I would not have you to be ignorant, brethren, concerning them which are asleep, that ye sorrow not, even as others which have no hope.” Justus Jonas was very careful after Luther’s death to care for his widow, Katharine von Bora, and their children. He used his skill with words to write letters to powerful nobles on the behalf of Luther’s family.

Justus Jonas realized that the work of Reformation was far from over. True, half of Europe had embraced the truth. Germany, Denmark, France, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, England, and Scotland had been transformed forever. But now the Council of Trent had declared open war on the Reformation, and powerful alliances were forming to crush the work of Reform. Temptation was strong, even among Reformers, to compromise with the Roman church. Even Dr. Melanchthon, as faithful as he was, tended to be willing to make compromises with Rome. This led to division among the Protestant nobles. As Philip Landgrave of Hesse once said, “Melanchthon is walking backwards like a crab.”

This was not the only trouble the Reformation faced in 1546. The Peasants’ Revolt had spilled blood all over Germany, and Luther and the Reformers were being blamed for it. Wild and radical splinter groups like those at Munster were spreading chaos and discord in Germany. Luther’s unhappy split with Zwingli had divided the Protestant cause into two camps on the question of the Lord’s Supper. The Reformation in England was vacillating with the whims of the Tudor monarchs. The Reformation in France was still underground, and persecution threatened to wipe out all the good that had been gained. The Reformation in Spain and Italy had already been drowned in the blood of the brutal Inquisition, and the Netherlands were threatened by the same. Denmark and northern Germany were dangerously close. To add to the dangers, the Muslim Turkish army was threatening Europe in the east. No, by the time of Luther’s death, the triumph of the Gospel was far from secure. Dr. Justus Jonas fully understood this. He knew that a people must be constantly reforming, never resting upon past victories but always seeking to obey the Word of God and daily submitting to His commands.

The very summer after Luther died, the summer of 1546, the first Schmalcald War broke out in the German states. This became a fascinating and bewildering period of German history. Recent peace with France had allowed Emperor Charles V to turn the fury of his armies against the Protestant nobles of the German states. The Schmalcald League had been formed as a mutual defense covenant among the Protestant German princes. Charles V placed two of the most powerful princes, John Frederick of Saxony and Philip Landgrave of Hesse, under imperial ban.

The war began well for the Protestants, but then Duke Maurice, a man who had been a part of the League of Schmalcald, betrayed his brethren and took the side of the Emperor. Halle, the city where Jonas was pastor, fell to the Emperor’s army in the autumn of 1546. Earlier in the war, in public prayer in his pulpit, Jonas had compared the Emperor to Diocletian and to Pontius Pilate. This had infuriated Charles V, and he now took vengeance by banishing Pastor Jonas from the city. Jonas was given ten days to leave Halle with his family and all his belongings. During these ten days, mercenaries were lodged in his house and a gallows was erected outside his door as a warning that he would be hanged if he remained. This was no empty threat, for the pastor who had been at Halle before Jonas had been murdered. Jonas left and went to Mansfeld. During his exile, Jonas received letters of support and encouragement from Protestant nobles. Even King Christian III of Denmark wrote Jonas a letter, comforting him in his exile and assuring him of the support of the people of Denmark.

On New Year’s day of 1547, the Protestant army of John Frederick entered Halle in triumph. It was a joyful day for the Protestants. Six thousand people flocked to welcome their exiled pastor back. Archbishop John Albert fled from his castle at the edge of the city to take refuge in territory held by the Roman Catholic armies. During the rule of the Saxon Elector over Halle, Jonas was able to remove the last vestiges of the Roman papacy. All the monks and nuns were driven out of the city. Evangelical ministers were placed in all the parish churches in the surrounding countryside. All images were removed.

But the fight was not over. In April of 1547, the army of the Emperor returned with reinforcements. This time, Jonas could expect no mercy. Although Mrs. Jonas was expecting a child at the time, Jonas loaded his wife and six children into a wagon and left the city under cover of darkness. He and his large family made their home in an isolated summer house located deep in the forest. From there, Jonas continued his work of encouraging and building up the churches. John Frederick, the brave Duke of Saxony, had been captured by the emperor and deprived of all his lands. Jonas wrote him several letters of consolation, encouraging the Elector to be faithful to the truth of God, even if he must suffer for it.

Jonas was soon called to the city of Hildesheim, where he became the pastor of two churches during these months of exile from Halle. Finally, when Maurice switched sides again, the Protestants were victorious. This allowed Jonas to return in triumph to Halle in the spring of 1548.

With the Passau Treaty of 1552, the Schmalcald Wars came to an end. Elector John Frederick was released from captivity. But again Jonas knew that the long-range struggle was not over. Just as he could not rest on the finished work of Luther, he could not rest on temporary successes. The Word of God demands constant reformation, continuing progress in the advance of the truth.

God permitted Justus Jonas to live to see the Peace of Augsburg ratified in September of 1555. A severe case of asthma had oppressed him all summer. But from his bed of affliction, he continued the work of reformation, writing letters of encouragement and advice to Protestants everywhere. With his wife and children gathered around his bed, Dr. Jonas asked that John 14 be read aloud. “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you . . . Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid.” With these words of consolation on his heart, Dr. Justus Jonas fell asleep in Jesus.

There is an important lesson we can draw from Dr. Jonas. The work of reformation is never over. We must never be content with past victories, but always endeavor to bring our own lives, our families, our churches, and our governments into conformity with the Word of God.

Bibliography

Justus Jonas: Loyal Reformer by Martin Lehmann

The History of the Reformation by J. H. Merle D’Aubigne