It was early dawn in the Wilderness. An eerie quiet pervaded the dim light of the morning. On the forest floor, wounded and dying men lay in dark puddles of blood. Above them, migrating warblers were starting to sing in the treetops, oblivious to the fact that 100,000 fighting men in gray and blue were spread out in the tangled woods below them, preparing for a mighty struggle to determine the outcome of Grant’s drive to break Lee’s lines and batter his way into Richmond.

On this morning, the dawn of May 6, 1864, the Confederate Army was in a desperately dangerous situation. A bloody day of battle had already taken place on the previous day, and the woods were already chocked with wounded and dying men. General Hancock’s Union II Corps was poised to break the lightly defended Confederate right flank. The two armies were near the very spot that General Thomas Jackson had routed the Union right flank a year earlier. Now the threat was the reverse – and Stonewall Jackson was not here.

General Lee was fully aware of the danger his army was in. He had sent courier after courier galloping toward the rear urging Longstreet to hasten forward along the Orange Plank Road to defend the Confederate right flank. They were supposed to be in place by midnight of the 5th, but now the morning of the 6th was dawning.

The birds had hardly begun to sing in the trees when the rattle of musketry opened up along the line. The weary men of A. P. Hill’s corps had been fought to a frazzle on the previous day, and they had little strength or ammunition left. Hill’s men stubbornly contested the ground, but overwhelming Union numbers forced them to give ground slowly. As the scattered rattle of musketry increased to a deafening and constant roar, it became evident that Lee’s flank was about to be broken and turned unless help arrived soon. Lee sent yet another message to Longstreet saying, “Longstreet must be here. Go bring him up!”

General Lee kept his seat upon Traveler as the Confederate infantry evaporated around him. Weary men with empty guns streamed toward the rear. One obstacle yet stood in the way of total disaster, a battalion of artillery under the command of a young officer named William Poague. Poague had started the war as a private in the Rockbridge Artillery. He had followed William N. Pendleton to the borders of Virginia to repel the first invasion. He had followed Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley campaign, and had been recognized and promoted. He had been with Jackson at Chancellorsville and with Lee at Gettysburg. Now he was a Colonel of artillery in command of his own battalion, facing an entire corps of the advancing enemy with 12 guns to oppose them.

Lee looked over at Colonel Poague and ordered him to prepare to fire upon the advancing artillery. Poague needed no orders. His gunners were already standing at their pieces loaded with double grapeshot. As the last of Hill’s stragglers came retreating past his guns, Poague realized that the entire Union Army was now upon him. Their blue coats were visible now through the trees.

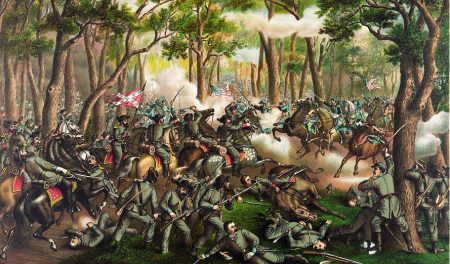

At Poague’s command, fire blazed from the muzzles of his twelve guns. The valiant old batteries of Stonewall Jackson were being heard again in the Wilderness! The belching guns filled the woods with a storm of fire that swept everything before it. Amid the wild confusion, shrieking horses, shouting officers, waving sabers, and screaming men cut down by the Confederate artillery, Colonel Poague remembered the rock in the midst of the storm. “Lee was perfectly composed, but his face expressed a kind of grim determination I had not observed either at Sharpsburg or Gettysburg. Traveler was quiet but evidently interested in the situation, as indicated by his raised head with ears pointing toward the front.” Colonel Poague and General Lee stood their ground as the guns of the battalion continued pouring grape into the ranks of the oncoming infantry.

After a few desperate minutes, twenty or so ragged soldiers ran into the clearing. They were running with faces set toward the enemy. General Lee asked them who they were. “Texas!” was the answer. General Gregg’s Texans, the advance guard of Longstreet’s corps, had arrived on the scene. General Lee personally formed the Texans into line of battle and prepared them for the charge before one Texan boy took Traveller by the reins and led Lee toward the rear, promising to go forward if only General Lee would go back. The Texans had arrived. The breach was filled. Longstreet was up. Lee was satisfied.

Jennings Copper Wise, a historian of Lee’s artillery, wrote of Poague that day at the Wilderness:

Poague’s single battalion of artillery . . . stood alone like a wall of flame across the enemy’s path. The great commander knew then full well that between him and disaster Poague’s battalion stood alone. What glory for a soldier! This single incident brought more of honor to the little colonel of artillery than most soldiers attain in a lifetime.

William Poague served loyally till the very end, when his command was surrendered with Lee at Appomattox. In his own modest memoirs which he wrote privately for the benefit of his children, Poague says very little of his own heroic action at the Wilderness, focusing the attention instead upon his faithful men and his adored commander.

William Poague returned home after the war and became an educator and a legislator. He served as Treasurer of the Virginia Military Institute and also as a trustee of Washington and Lee University. He was a faithful elder at Jackon’s church, Lexington Presbyterian Church for many years. Poague was a steady bachelor and was often teased by his friends about his status. He surprised everyone by his marriage at the age of 43 to Miss Sarah Moore. The couple was blessed with four children. William Poague lived to the advanced age of 78, and was buried in the same cemetery where the mortal remains of Stonewall Jackson await the resurrection.

In our day of widespread fear and discouragement in the face of an advancing enemy of secular humanism and modern philosophies, we need young men with the courage and faith of William Poague to stand calmly and boldly at the side of our Great Commander. The book of Isaiah gives us this word of encouragement, “When the enemy shall come in like a flood, the Spirit of the LORD shall lift up a standard against him” (Isaiah 59:19).

Bibliography

Gunner with Stonewall by William Poague

R.E. Lee by Douglas S. Freeman