The fur trade saved the Pilgrims’ Plymouth colony from financial ruin. Setting up a new colony wasn’t cheap, and the realization hit quickly after their arrival in 1620 that there was no quick and simple way to pay back their debts to their London backers. The decision to vigorously pursue their trade for furs with the Natives is what finally made the colony profitable. The town of Plymouth was not well positioned to carry on the trade since it had no river nearby to provide easy access to the interior. At first they just sailed up and down the coast in their small shallop, conducting the trade out of it. At length they realized that it would be better to do this out of established trading posts.

In the decades that followed they established five trading posts spread across New England. Understanding these is critical to grasping the story of the Plymouth Colony. They represented not only financial profit, but the spread of Plymouth’s territory and influence, and their points of interaction or even armed conflict with other governments – English, Native and other Europeans.

Despite their importance, I have not yet found any simple summary or map of the trading houses. Here I intend to remedy that. My focus will be on their location and status today. To give a complete overview of their history isn’t simple, as the record is unclear on many important details.

Aptuxet

We will start with the one closest to Plymouth. The Aptuxet Post was just 20 miles south on Cape Cod. It was built in 1627 on the Manamet River which today has become the Cape Cod Canal. In 1852, excavation was begun at the site where the post was believed to have been, and it was fully excavated by 1929. There is, however, good reason to believe that they got the wrong site, and the foundations excavated were actually for a later building. Nonetheless, a replica of the trading post was built on those original foundations, and it still stands today, over 90 years later, as the Aptuxet Trading Post Museum.

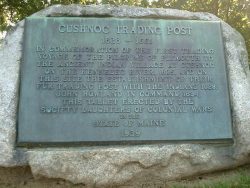

Cushnoc or Kennebec

They built the next trading post a few years later but much further away – on the Kennebec River likely where the city of Augusta, Maine now stands. This post was called the “house at Kennebeck” or Cushnoc, meaning “head of the tide,” as the tide on the Kennebec River reaches all the way inland to that site. Again, there is some uncertainty as to the location of this post. The main issue is whether Cushnoc and Kennebec were two names for the same places. The site of Cushnoc was discovered and excavated in the 1980s. Although the textual and archeological record are not 100% definite, I think they strongly indicate that the site discovered was both Cushnoc and Kennebec. There isn’t much to see at the site today, however, it is directly outside Old Fort Western, a surviving 18th century fort and trading post.

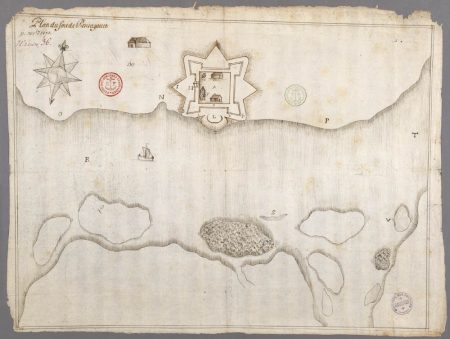

Penobscot or Pentagoet

In 1630 the Pilgrims joined with their former comrade and future enemy Isaac Allerton in the Penobscot Trading Post, on Maine’s Penobscot Bay, where the Penobscot River joins the ocean. This post was in Acadia, an area of French control. The Pilgrims didn’t hold onto it for long, and it is better known as Fort Pentagoet, which was, for a time, the capital of French Acadia. The site can be visited, though none of it can be seen today. It was thoroughly excavated, though most of what was found corresponded to the later French settlement rather than the Englishmen’s short time there.

Sowams

The Sowams Trading Post is one about which less is known. It was established 1631 in what is now Barrington, Rhode Island at the main village of the Wampanoag. Its ultimate fate is a mystery and the exact site is unknown and undiscovered.

Matianuck

Last is the Matianuck Post on the Connecticut River in what is now Windor, Connecticut. This was built in 1632 and was a scene of fierce competition for the Indian trade. In the end, Plymouth was forced to sell most of the surrounding land. The site where it is presumed to have been located is now beneath a sports field and has not been excavated.

Sources

My research on Bradford and the fur trade is ongoing, but for those interested in digging deeper into the Pilgrim’s fur trade I suggest the following books:

Cushnoc: The History and Archaeology of Plymouth Colony Traders on the Kennebec by Leon Cranmer (the work from which most of the facts in this article are drawn)

Making Haste from Babylon: The Mayflower Pilgrims and Their World, a New History by Nick Bunker

Debts Hopeful and Desperate: Financing the Plymouth Colony by Ruth A. McIntyre

Good evening I just read your post on the five trading locations of the Plymouth colony

Looking for information on the Penobscot post at Pentagoet,.

I was just recently made aware of the genealogy in our family and is it turns out Thomas willett would have been my ninth great grandfather and supposedly he was the one that established the Penobscot post and wondering if you could provide me with any more information on that Thank you

billmackowski@gmail.com

There’s no book that focuses specifically on the Peneobscot trading post. But here are some resources that will help you as you research the subject.

The French at Pentagoet 1635-1674: An Archaeological Portrait of the Acadian Frontier by Alaric and Gretchen Faulkner focuses on the French time at the site, but they did the excavation of the site and discovered some Pilgrim artifacts.

Cushnoc: The History and Archaeology of Plymouth Colony Traders on the Kennebec by Leon Cranmer is on the excavation of another trading post, but it may give the best idea of what life was like at Penobscot.

Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation touches on it, with more information in the footnotes in the edition mentioned here: https://discerninghistory.com/2021/09/the-best-edition-of-of-plymouth-plantation/