A rescue ship drifted slowly toward a rocky coastline at “the end of the earth.” Long feared by sailors for its violent storms, its hidden rocks, and its savage natives, this desolate region of rocky islands is known as Tierra de Fuego. It is located off the coast of Patagonia, the southernmost tip of the mainland of South America. The mission of this rescue ship was a desperate one, to locate and assist seven missionaries who had come to bring the Gospel of Jesus Christ to these desolate islands.

Seven dedicated men had landed here on December 17, 1850 with the purpose of evangelizing the inhabitants of these islands. It was known that they had brought six months of supplies, but nothing had been seen and heard from the mission party for over a year. Every effort to send them fresh supplies had failed and their fate was unknown.

Finally, a British naval vessel has been sent to find the lost men. As the rescue ship coasted toward the rocky coastline, they did not find any of the missionaries at the point where they were known to have landed. Instead, they found a crude inscription painted on a large rock, directing them elsewhere. Following the directions, they met with a grim sight. Three bodies were seen near the water. One was lying in a shallow boat. Another body was spotted at the waterline, beaten to gruesome pieces by the pounding surf. The third body was seen lying half-buried further up the beach, probably buried by the kind but weak hands of one of his companions.

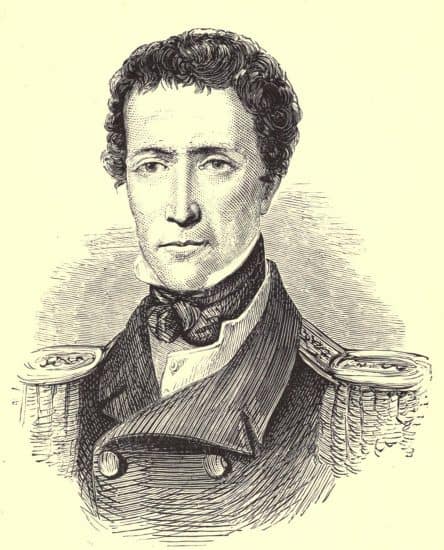

Because a bad snowstorm was approaching, the rough seas and a strong wind forced them to temporarily suspend the search. When the weather permitted a more thorough search, more bodies were found. But the body of their leader, a former British naval captain named Allen Gardiner, was still missing. For a while, it was hoped that he might still be alive. But his body was at last discovered. He had not been dead long, and it was evident that he had fought manfully for life.

Captain Allen Gardiner had dressed in three suits of clothing to protect himself from the cold winds. He had drawn stockings over his arms to give extra warmth. The seagulls had begun to work on his body, but his manly face was still recognizable. He had his Bible with him, and many precious promises of consolation had been underlined by the dying Captain. He had also written a final letter to his wife and children, tucking it safely where it could be found and delivered. With him also was his journal, and the final entries told, with touching detail, the story of the final days of a life well-lived. The last entries of the starving man were not the words of defeat and despair, but words of hope and victory. The last words, weakly written, were a reference to the glories of New Jerusalem where there will be “neither hunger nor thirst.”

From a human standpoint, it would seem that the mission effort was a complete failure. Not a single native of Tierra de Fuego had been converted, and at the death of Allen Gardiner, the islands were still in the firm clutches of darkness, superstition, and cruelty.

Indeed, the natives of Tierra de Fuego were regarded as among the most primitive and barbaric people on planet earth. Any European vessel that wrecked in these islands could expect no mercy from the ferocious inhabitants. The Fuegians were notoriously cruel and cannibalistic, not only to stranded sailors from the outside world, but even to their own. During storms, the Fuegians were known to throw their own children overboard to lighten their native boats. There were very few elderly Fuegians, because adult children would strangle their own parents and then eat them.

To add to these shocking cruelties, the Fuegians were regarded as degraded, stunted, ugly, and stupid. Their speech was hoarse and guttural, and was regarded as entirely unintelligible, being compared to a man clearing his throat. When Charles Darwin had sailed around the southern tip of South America, he had written about these savages, referring to them as “wild animals” and taking them for an example of the link between apes and men. Darwin said of the Fuegians, “such were our ancestors.” Consistent with his view of the survival of the fittest, Darwin belittled missionary efforts to help such primitive people, and encouraged the elimination of the Fuegians, saying, “hardly any one is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed.” In contrast to the opinion of Charles Darwin, the prophet Zechariah prophesied of the Lord Jesus Christ, “His dominion shall be from sea even to sea, and from the river even to the ends of the earth.” Believing this promise, Captain Allen Gardiner gave his life to win the ends of the earth.

Allen Gardiner was born into a Christian home in Berkshire, England on June 28, 1794. His father and mother were devout Christians, and they read the Bible daily to their son in family worship. As a boy, Gardiner came to admire the exploits of Lord Nelson and longed to go to sea. At the age of 13, young Gardiner went to the Naval College in Portsmouth and was soon a midshipman. He gained experience quickly as an officer fighting against the United States in the war of 1812. He commanded his own ship at the age of 24 and sailed around the globe in the service of the Royal Navy in the glory days when Britannia truly ruled the waves.

During his youthful days of naval glory and adventure, Captain Gardiner turned his back upon the God of his fathers. The rough life of a sailor made him proud and profane. But God would not let him wander far. Letters from his pious parents continued to reach him in the farthest reaches of the globe, warning him of the deadening effects of sin upon the conscience. A friend of his mother’s also wrote him, pleading with him to bow the knee to Jesus Christ. Eventually, the Word of God penetrated the heart of Captain Gardiner and he was converted by the grace of God.

Captain Gardiner had seen the effect of the Gospel upon the hearts of former savages in places like Tahiti and the coast of Africa. As a new Christian with naval experience around the globe, he dedicated his life to taking the Gospel of Christ to places unknown. He left the service of the Royal Navy to carry the banner of Jesus Christ to the distant reaches of the globe. He married a Godly wife and sailed for Africa where he gave the Gospel to the Zulus. When war ended his work there, he took his wife and children to the Pacific Ocean and pioneered the work of the Gospel on Papua New Guinea in spite of the scorn of Dutch officials who said that he might as well try to instruct the monkeys. Undeterred, he laid the groundwork for future triumphs in New Guinea. His next place of service was the steamy jungles of South America, where he labored among various tribes in the areas that would eventually be Chili, Argentina, and Bolivia.

Returning to England, Gardiner sought to awaken British Christians to the vast needs of South America. Having sailed through the Straits of Magellan many times, and having witnessed the dark paganism of the Fuegians, he set his heart upon winning for Christ the unreached savages of the Tierra de Fuego. Gathering six volunteers, he sailed for the dark islands at the bottom of the world. It was there, unable to obtain fresh supplies, that Captain Gardiner and the other six missionaries starved to death on the rocky coastline. Their death was not in vain. The interest of Britain had become aroused by the story of the lost men, and a generation was inspired by Gardiner’s zeal to reach “the most hopeless.” In addition to the seven men who starved, eight more missionaries were lost in the effort to reach these islands, all slain by the savage Fuegians. But the conquest continued. The slogan of the Patagonian Missionary Society was derived from the words of their fallen leader, “Hope deferred, not lost.” Allen Gardiner’s own son courageously went back to Tierra de Fuego, and was an instrument of reaching the very people for whom his father had given his life.

After a few short years, the dominion of Christ was established in this remote corner of the earth. The remarkable change among the Fuegian tribes came to the attention of Charles Darwin, who wrote in astonishment, “I could not have believed that all the missionaries in the world could have made the Fuegians honest.” Perhaps the greatest tribute to the life and sacrifice of Captain Allen Gardiner is the fact that the evolutionist Charles Darwin in his later years became a regular contributor to the funds of the Patagonian Missionary Society.

Bibliography

The Adventures of Missionary Heroism by John C. Lambert

Taking the World for Jesus by Kevin Swanson

darwinian evolution is not fully true but we have proof of some evolution but you should know ancient astronaut theory which makes god compatible with modern science plus discoveries prove human civlizations like egypt are older than noahs flood plus both the bible and koran are flawed they cant be the only way to salvation that they claim to be while having contradictions. sumeria is also older than noahs flood nimrod is originally sargon.