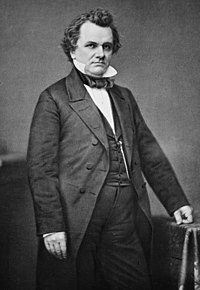

Stephen Douglas was one of the most important politicians during the two decades leading up to the Civil War. Today he is mostly known as the rival of Abraham Lincoln, but he was an important leader in the Senate. He was instrumental in passing bills which changed the course of the United State’s history. He was known as the Little Giant, because, although he was short in stature, he was a giant in politics.

Early Life

Stephen Arnold Douglas was born on April 23rd, 1813 in Vermont. As a young man, he became a cabinet-maker, and spent time avidly studying politics. He abandoned cabinetry, and after attending school, immigrated west at the age of 20. He settled in Illinois and taught school while he studied to become an attorney. After getting his license, he opened a law office. His friends used their influence to gain him the appointment to county attorney. He was soon elected to the Illinois legislature. He was an active member of the Democratic Party, and was appointed Illinois Secretary of State for his work in his party. As Secretary of State, he had the time, and resources, to continue deeper in his law studies, which he wished to pursue further. His next appointment was to the Illinois Supreme Court. By eastern standards, he would not have been seen as qualified, but Illinois was still the frontier, and the court was conducted differently.

House of Representatives

With the census of 1840, Illinois was given several more representatives in the House, and Douglas was elected to one of the seats. At the age of 30, he became a member of Congress. Douglas was likeable and intelligent. He gained notoriety through his defense of Andrew Jackson, his boyhood hero. While a general, Jackson had proclaimed martial law in New Orleans, and was fined $1000 for contempt of court. Douglas later met Jackson who said to him:

I never could understand how it was that the performance of a solemn duty to my country – a duty which, if I had neglected, would have made me a traitor in the sight of God and man, could properly be pronounced a violation of the Constitution. … I thank you, sir, for that speech. … Throughout my whole life I never performed an official act which I viewed as a violation of the Constitution of my country; and I can now go down to the grave in peace, with the perfect consciousness that I have not broken, at any period of my life, the Constitution or laws of my country.1

When it was proposed to annex Texas, there were debates over whether the Constitution allows Congress to annex territory. Douglas argued it did, because it was necessary to add new states. He pushed for territorial expansion of the United States, saying on the floor of Congress:

Our federal system is admirable adapted to the whole continent; and while I would not violate the laws of nations, nor treaty stipulations … I would exert all legal and honorable means to drive Great Britain and the last vestiges of royal authority from the continent of North America, and extend the limits of the republic from ocean to ocean.2

Douglas began to gain influence in Congress, and was made the chairman of the Committee on Territories. When the Mexican War came, Douglas supported it as well.

Senate

In 1846 the Illinois legislature prompted him to the Senate. He continued to rise to prominence in that body as well. Being from the rough, western part of the country, he was at times offensive to other Senators and Representatives. However, this was in some part the character of Congress at the time. In just a few years, Charles Sumner would be caned on the floor of the Senate. One man recorded that the only people in Congress “who do not have a revolver and a knife are those who have two revolvers.”3

In 1847 Douglas married Martha Martin from North Carolina, who was the cousin of a Congressman. When his father-in-law died, his wife inherited a plantation with 100 slaves, and later these were used to accuse him of hypocrisy. Douglas was worried that the Union might be dissolved. There were many disagreements between the North and South over slavery, and Douglas worked to keep the nation unified through compromise bills. He was instrumental as one of the main authors of the Compromise of 1850. Douglas believed in what was called Popular Sovereignty. He believed that each territory should have the right to decide to be free or slave. He argued in the Senate:

I am not … prepared to say that under the constitution, we have not the power to pass laws excluding negro slaves from the territories…. But I do say that, if left to myself to carry out my own opinions, I would leave the whole subject to the people of the territories themselves…. I believe it is one of those rights to be conceded to the territories the moment they have governments and legislatures established for them.4

Douglas, as with many others as the time, believed that slavery was on its way out. He did not think that the slaveholders would settle new territories. Indeed, he thought that eventually the entire South would emancipate its slaves.

Douglas’ rapid ascension in the leadership of the Democrat party led to his being suggested as a presidential candidate in 1850. He ended up not winning the nomination, but was reelected to the Senate in 1852. In 1854 Douglas designed the Kansas-Nebraska act, which was an application of popular sovereignty to organize the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. In a speech in favor of his bill, Douglas pointed back to the founding of the country as an example of popular sovereignty:

This was the principle upon which the colonies separated from the crown of Great Britain, the principle upon which the battles of the Revolution were fought, and the principle upon which our republican system was founded.5

He concluded by saying this:

I have not brought this question forward as a Northern man or as a Southern man. I am unwilling to recognize such divisions and distinctions. I have brought it forward as an American Senator, representing a State which is true to this principle, and which has approved of my action in respect to the Nebraska bill. I have brought it forward not as an act of justice to the South more than to the North. I have presented it especially as an act of justice to the people of those Territories, and of the States to be formed therefrom, now and in all time to come.6

Douglas contrived to get his bill passed, but not everyone agreed with him. He was called a Traitor and Judas by those in the North who said he was turning the territory over to slavery, and opposed by Southerners who wanted guarantees of slave holding territories.

Stephen Douglas was a popular leader. His followers were not bought, they were loyal to him personally. He made friendships with many, and by using his excellent memory, he was able to make many who helped in him in small ways feel important. In Congress, he was a skilled debater. He often gave very powerful speeches without notes. Harriet Beecher Stowe described him:

This Douglas is the very ideal of vitality. Short, broad, and thick-set, every inch of him has its own alertness and motion. … His forte in debating is his power of mystifying the point. With the most off-hand assured airs in the world, and a certain appearance of honest superiority, like one who has a regard for you and wishes to set you right on one or two little matters, he proceeds to set up some point which is not that question, but only a family connection of it, and this point he attacks with the very best logic and language….7

Douglas was again proposed to be the Democratic nominee for president in 1856, but again he was not chosen, and James Buchanan was elected to the presidency. In Kansas, Douglas’s law was not having its intended effect. Instead of a simple vote on slavery, both sections were racing to see which side would gain the majority. A Kansas Constitution was proposed which had Buchanan’s support, but Douglas did not believe it was fair or the true will of the people of Kansas. So he revolted from the President’s leadership and stood up to him in the Senate.

Douglas returned home from Washington to campaign for re-election to the Senate. He was being challenged by Abraham Lincoln. They agreed to a series of debates throughout the state of Illinois to clarify their positions, even though the appointment was made by the legislature and not by the votes of the citizens. These debates were printed and distributed through the nation and read by many. Douglas prevailed by being re-elected to his Senate seat.

Election of 1860

Two years later, the Democratic convention was held to determine the presidential nominee for 1860. The debates were heated. The Southerners wanted their property in slaves protected by the federal government even if they moved into the territories. Douglas wanted the people of the territories to be able to decide for themselves. Douglas’ platform was adopted by a majority, but the Southern representatives left the convention. The “Rump Convention,” consisting of those who remained was not able to get enough agreement on a single candidate. The convention adjourned after it became clear that Douglas would not be able to get fifty more votes. When they met again in Baltimore, the Southern delegates were not counted, so Douglas was appointed the nominee, but the split in the convention destroyed the Democrat’s chance for either of their nominees to be elected. As nominee, Douglas broke tradition by campaigning for himself. The practice at the time was to send out representatives to argue your merits on the campaign trail.

Douglas lost the election to Lincoln, and states began to secede because of it. Douglas, who believed the disagreements could be worked out, saying, “I hold that there is no grievance growing out of a non-fulfillment of constitutional obligations, which cannot be remedied under the Constitution and within the Union.”8 Douglas did not believe in secession. He thought the Union could not be dissolved, but he believed that all peaceful means must be used before resorting to war to restore the Union. He said:

We can never acknowledge the right of a State to secede and cut us off from the ocean and world, without our consent. But in the question of force and war until all efforts at peaceful adjustment have been made and have failed. The fact can not longer be disguised that many of the Republican leaders desire war and disunion under pretext of saving the Union. They wish to get rid of the Southern senators in order to have a majority in the Senate to confirm Lincoln’s appointments; and many of them think they can hold a permanent Republican ascendancy in the Northern States, but not in the whole Union.9

Douglas’s efforts to preserve the Union through Constitutional agreements failed, partly, as he said, because of the influence of the Republican leaders.

Eventually, Douglas believed that war was justified to preserve the Union. He worked with Lincoln, even though a few months before they had been running against each other. Douglas returned to Illinois and encouraged the people of his state to gather to support Lincoln. He fell sick there, and after a few weeks of illness he died on June 3rd, 1861. When asked what he wished to tell his sons, he said this, “Tell them to obey the laws and support the Constitution of the United States.”10

1. Stephen A. Douglas: A Study in American Politics, by Allen Johnson (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1908) p. 82.

2. Ibid, p. 88.

3. James Hammond to M. C. M. Hammond, April 22, 1860.

4. Stephen A. Douglas: A Study in American Politics, p. 185.

5. Ibid, p. 253.

6. Ibid, p. 253-254.

7. Ibid, p. 295.

8. Ibid, p. 445.

9. Ibid, p. 447-448.

10. Ibid, p. 489.