A row of sweating men toiled in the hot sun, reaping their wheat. With one hand they grasped a handful of grain, and with the other hand they cut the grain with a sickle. This was one of the most common scenes in the history of humanity. The scene would be the same whether the men reaping were Egyptian slaves on the banks of the Nile River in 2000 B. C., Israelite tribesmen in the hills around Bethlehem in 1100 B. C., Babylonian farmers on the banks of the Euphrates River in 700 B. C., Frankish peasants in the valley of the Marne in A. D. 800, Ukrainian serfs in the valleys of the Ural Mountains in A. D. 1400, or American farmers in Shenandoah Valley of Virginia in 1816. Over the thousands of years that man has been cultivating grain, the costumes have changed significantly, the languages have come and gone, Empires have risen and fallen and been forgotten, but the methods of reaping grain had remained largely the same.

It was a warm day in June in the mountains of Virginia. In 1816, grain was still reaped by hand, and sickles were still the main instrument of the harvest. Men and boys labored from sunup to sundown cutting the standing grain with their sickles and scythes. Others came behind them to rake the grain into piles, bind it into sheaves, and load wagons to carry it to the place where the grain would be threshed before milling. But this year, by God’s grace, it would be different.

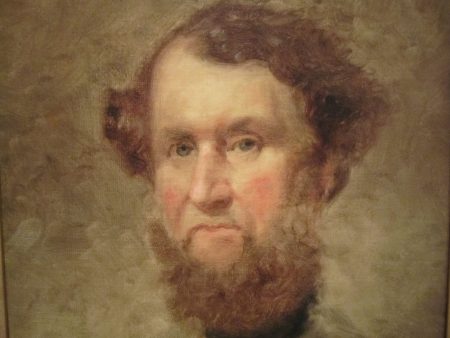

A strong and muscular farmer of Scots Irish ancestry had determined that he would try something new. Robert McCormick was not necessarily intending to change the course of history or to feed the world. He was only trying to save the valuable labor of his men for other worthwhile endeavors. He had invented a “reaping machine” that would cut the grain automatically. A row of short sickles stood waiting for the grain. Revolving rods in front of these sharp sickles were set to grab the wheat and pull it against the blades. The entire machine was pushed through the field by two horses from behind.

A small crowd of interested neighbors had gathered to watch the experiment. The farmer’s wife and children had also gathered to see the performance. A young boy named Cyrus watched his father with admiring eyes. He loved and admired his father with all his heart. Even at the age of seven, he loved to be in his father’s workshop. In addition to farming his land, Robert McCormick operated two gristmills, two sawmills, a smelting-furnace, and a blacksmith shop. In this busy shop, Robert had been working on his machine on and off for years. He was now ready to make his great experiment. Several farmers from the surrounding area had come to observe their neighbor’s attempt. Robert brought his horses to his contraption and brought them to their pushing positions. This novel arrangement was new to the horses, but they pushed with goodwill and sent the machine forward.

Cyrus watched in awe as the machine went forward. The gathering arms pulled the grain toward the sickles and some of the grain was cut. But alas, the contraption did not work as hoped. The tough stalks bunched up against the sickles, and the machine eventually jammed. The farmers standing by the fence shook their heads. The reaper that could not reap was dragged off the field, the lathered horses were sent back to their stalls, and the event became one of the tales of the neighborhood. The farmers by the fence went back to their age-old method of reaping grain by hand, and whenever the name McCormick was mentioned, they smiled at the idea that a machine could replace them. But Cyrus did not doubt. His admiration for his father fueled his desire to see his father succeed. In their workshop, the McCormick family continued to tinker with new ideas. The father had inspired the son with a desire to see a great thing done and done well. Flexibility is the willingness to change plans or ideas to best accommodate those who we serve. Young Cyrus McCormick realized that his father had a good idea, and that a modification of the mechanism of this machine might achieve his father’s goals.

Fifteen harvests came and went with no real improvement. The McCormick machine could cut grain if all conditions were perfect, but it could not do so effectively if the wheat was wet, laying down, or mixed with weeds. Also, the machine left the cut grain lying in heaps. By this time, Cyrus was a young man of twenty-two years. He still worked alongside his father, but he had taken his father’s place as chief inventor. The father allowed the son to experiment with his own ideas. At last, he had one he thought would work. The son gave full credit to the father, but the father also gave full credit to the son for his brilliant improvements.

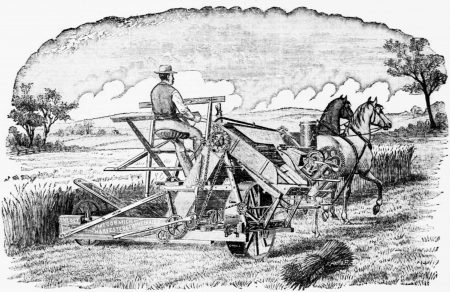

Cyrus had replaced his father’s fixed sickles with an idea of his own devising, straight blades that were arranged by gears to move in a reciprocating motion, cutting the grain as it came into the reach of the reciprocating blades. Cyrus had replaced the revolving fingers with fixed fingers of wood that held the grain upright as it was fed into the blades. To fix the problem of grain that was lying low, he had devised a reel to pick up the grain that was low and pull it upward to feed it into the fingers and the knives. Cyrus had also added a platform to catch the cut grain as it came from the knives. He also had rigged up a system for hitching the horses to the side of the machine, so that it could be pulled rather than pushed.

One July day in 1831, Cyrus pulled his machine out of the workshop and into the bright light of the summer sun. Most of the fields around had already been harvested by the old-fashioned method of sickle. But Cyrus had requested that his father leave a patch of wheat standing. He had a new invention to try out on this wheat. He had worked hard to have his “reaper” finished in time for the harvest of 1831, but the time of harvest had come and most of the fields were already cut by the old method.

Under the hot sun, the young man’s mother and father had come out of the farmhouse to witness their son’s attempt to make a reaping machine. A few excited brothers and sisters made up the entire audience. No newspapermen were there, and nobody in distant places like Chicago or New York would have cared anything for the scene. The neighbors would have scoffed to see the son trying the same thing his father had tried before him. No man knew that the destiny of worldwide agriculture and the hope for hungry humanity was being hooked to a team of horses on the McCormick farm.

The young inventor hitched his team to a curious mechanism consisting of wooden forks, metal blades, and various gears and wheels. Most farm horses would have shied away, but the McCormick horses were used to things like this. They leaned forward into the harness. The eyes of the young inventor shone with the thrill of success as his machine moved forward. The blades glided back and forth in a reciprocating motion that cut the grain and left it in yellow piles on the platform. The young man looked at his parents and they smiled quietly as only parents can.

By the time that Cyrus McCormick died in 1884, five hundred thousand McCormick reapers were being used on every continent of the globe. At every hour of every day of every month, somewhere in the world it was the time of the wheat harvest, and a McCormick reaper was busy in the field. Old Robert McCormick would have been astonished to see the vast factory in Chicago, Illinois that stretched over more acres than he had farmed in old Virginia. The McCormick reaper had fed the world, fueled an economy, and launched the United States of America to world prominence as an agricultural and industrial giant. In the year he died, the wheat fields of the world produced 2,240,000 bushels. The prayer taught by our Lord above the wheat fields of the Plain of Gennesaret had been answered in a billion homes across the world, “Give us this day our daily bread.”

The thing that made Cyrus McCormick successful was his ability and willingness to adjust his plans to meet new problems. He overwhelmed all his competitors, survived dozens of challenges to his patent, modified his machine at the request of the farmers of the world, and built his plant to match the new demands of a glowing horizon. Cyrus McCormick was a firm Christian who raised a fine family to carry on the family heritage. He was a rugged and dedicated businessman who sought to serve his fellow man. His plan of work was expressed in his own words, “Do one thing at a time, and the hardest thing first.”

Thank you for sharing this wonderful piece of history…

Also from a man that loved the Lord…

It’s amazing how God rewards those who diligently seek Him…