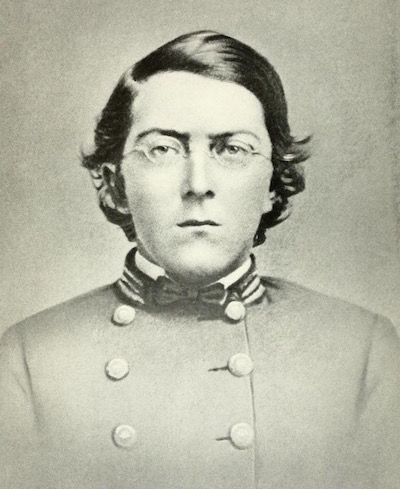

On June 29, 1841, a baby boy was born to the Pegram family in Richmond, Virginia. His parents named him William Ransom Johnson Pegram. The Pegrams were an honorable and respected family in the area. William’s grandfather had been a major general in the War of 1812. His father was a lawyer and one of the most respected bankers in Richmond. Little Willy Pegram was the youngest son of five children. His happy and carefree childhood was shattered by tragedy when the boy was only three years old. Willy’s father was on board a steamboat on the Ohio River when the boiler suddenly exploded. Mr. Pegram survived the initial blast, but while seeking to save women and children was drowned in the Ohio. His body was never found.

Willy had only vague memories of his father. His loving mother, Virginia Pegram, raised her five children to honor their father’s memory. She was a pious and Godly mother who lived as a splendid example of a faithful widow. Willy was devoted to his older brother, John, who became a father figure to him. The Pegrams were members of the Episcopal church, and at an early age, Willy recognized his need of salvation through the shed blood of the Lord Jesus.

In the fall of 1860, Willy entered the University of Virginia with the intention of studying law. Already, the clouds of war were looming on the horizon. Willy helped to organize a militia known as the Southern Guard, and the students regularly drilled on the lawn of the University. When Fort Sumter was fired upon in April of 1861, it became very clear that war was inevitable. Willy left the University of Virginia in Charlottsville and returned to Richmond to join Company F, recently organized for the defense of Virginia. He was twenty.

After a short stint as an infantry private, Willy was became aware of a new six-gun battery of artillery called the Purcell Artillery that needed help in drilling new recruits. He was temporarily appointed a drillmaster, and was so faithful in his duties that he found himself elected lieutenant in the battery. The young officer quickly established a reputation for diligence, efficiency, and humble leadership. His men and his superiors valued his quiet courage and devotion to duty. The spring of 1861 was spent in minor skirmishing against Federal flotillas on the James River. Pegram proved his courage under fire.

At the First Battle of Manassas, the Purcell Artillery unlimbered near the end of the battle and took part in the shelling of the retreating Federal forces as they withdrew from the field.

Willy Pegram was promoted to captain of the Purcell Artillery when he was still only twenty years old. He spent the autumn of 1861 disciplining his men and preparing them for the renewal of combat in the spring.

Pegram’s battery took its first severe test under fire during the bloody battles around Richmond during the Seven Days Campaign. Pegram knew that he was fighting for his mother and sisters in nearby Richmond, who could hear the roar of his cannon. At Mechanicsville on June 26 of 1862, Pegram’s battery took heavy fire while holding a critical position. Captain Pegram sat erect in his saddle, unmindful of the crashing of shells and solid shot around him. Nearby a single solid ball tore through three horses, ripped a man’s leg off and then killed a man. Captain Pegram held his ground.

At Beaver Dam Creek and Malvern Hill, Pegram similarly distinguished himself. Wherever the action was the hottest, there Captain Pegram could be found, dealing out grapeshot and canister to the enemy at close range. At the start of the Seven Days, Pegram had 90 men under his command. Of these, 57 were killed or wounded over the course of the action. But McClellan had been driven from Richmond. Other officers liked to tease Willy that he needed to get so close to the enemy because of his severe nearsightedness. He always wore spectacles, even in battle, and it was said that he advanced so close to the enemy because he needed to see his targets better!

At Cedar Mountain during the lead up to Second Manassas, Pegram served his guns under the eye of Stonewall Jackson. When the surging lines of Federal infantry advanced on his guns, Pegram waved the Confederate battle flag and shouted “Action Front!” and ordered his men to pour double charges of canister into the faces of the advancing enemy. On this field, Captain Pegram took four bullet holes through his coat. It was there that he told his men, “When the enemy takes a gun from my battery, look for my dead body in front of it.”

Pegram’s battery served in the capture of Harper’s Ferry in the fall of 1862, and Pegram was able to bring one gun when A. P. Hill came at a rapid march to the rescue at the end of the bloody day at Sharpsburg.

It was at Fredericksburg that Pegram’s battery saw heavy action again. From an exposed position on Prospect Hill, Pegram commanded his own as well as another battery. His well-directed fire was devastating against the Federal infantry advance. But opposing shells from the Union artillery made his position a very dangerous one. At one point, his artillerists abandoned their guns and fled for cover.

As shells burst all around him, Pegram tore down the Confederate battle flag and threw it around his own shoulders as a shawl. Boldly, he strode forward alone into the midst of the abandoned guns, urging his men to rally and hold their position. He made himself a clear crimson target to the enemy gunners. Inspired by the courage of their commander, the gunners cheered and rushed back to man their position at the guns.

Back in Richmond, Willy’s mother read in the newspapers this glowing description of her son, “He is a small man, wears spectacles, is quiet and modest . . . yet he gets his battery always into the hottest place, and always is conspicuous.” During the winter lull in the fighting, the artillery was reorganized, and Willy Pegram was promoted to major. A spiritual revival swept through Lee’s camps during that winter, and Major Pegram took eager delight in the progress of the revival.

At Chancellorsville, Pegram’s battalion was unlimbered atop Hazel Grove as Pegram instantly recognized the importance of the position. Other artillery officers soon joined him until the hill was crowned with over 40 cannon. In one of the most dramatic artillery bombardments of the war, Pegram’s guns crushed the confused and broken lines of Hooker’s infantry divisions.

At Gettysburg, Pegram took part in the bombardment that prepared the way for Pickett’s famous charge. At the Wilderness, Pegram held the position between A. P. Hill and Longstreet as Grant hammered his forces against the Confederate lines. Throughout the Overland Campaign, Grant’s men found Pegram’s batteries always planted in their way.

As officers were cut down and vacancies formed by death, Pegram was promoted to colonel. Many called him “Lee’s boy artillerist.” Robert E. Lee said of Pegram, “no one in the army had a higher opinion of his gallantry and worth than myself.”

After serving with distinction throughout the long and agonizing siege of Petersburg, Pegram found himself at a rural crossroads called Five Forks. As before, so now, Willy Pegram would not leave a position he had been ordered to maintain. Mounted on a white horse, the boy colonel calmly surveyed through his spectacles the overwhelming numbers of massing and converging against him. He ordered his men, “Fire your canister low!”

Unwilling to retreat, unable to advance, Colonel Willy Pegram held his ground. In the midst of his beloved guns, he fell at his post mortally wounded. Willy’s last words were for his mother and sisters. In the words of a fellow officer who was with him, Willy’s death was “as gentle as an infant.” Lee’s boy artillerist, unwilling to abandon his ground, made a lasting impression on all who knew him.

Bibliography

Lee’s Young Artillerist: William R. J. Pegram by Peter Carmichael

Three Christian Confederate Artillerymen