A while back I was reading The Problem of Slavery in Christian America by Joel McDurmon, and I came across a reference to Puritan New England that was new to me, and actually quite surprising. McDurmon writes:

In 1645, Edward Downing wrote his brother-in-law, Governor Winthrop, expressing the desire for a ‘juste warre’ with the Pequot so he could trade captive Indians for black slaves on the transatlantic market. His comments show the outlook of the elite at least, if not others as well: ‘The colony will never thrive … until we get … a stock of slaves sufficient to doe all our business.’1

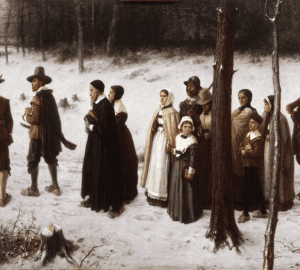

This certainly piqued my curiosity, since that is a time period in which I have a particular interest at the moment. His accusation is pretty shocking – that the New England Puritans, who we may think of as godly and pious Christians, were actually seeking to build their society on slavery, to the point that they would go to war with a neighbor in the hope to get captives. This is not original to him, but that’s where I found it, and that’s the most likely place where people in my circles would come across it. So let’s try to figure out whether it is actually true.

The Source

The first thing to do when dealing with a short quote like this is to find the original source. In this case I haven’t been able to find the complete letter online, but I did find a much longer section quoted. This is where the trouble began. We’ve been told this was a letter from Edward Downing, in fact it was Rev. Emanuel Downing. He was a Puritan, and was indeed married to Lucy, the sister of John Winthrop. Although Winthrop spent a lot of time as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and was certainly an eminent figure in the colony, in August 1645, when this was written, he was only deputy governor.2 In his letter, Downing wrote this:

A war with the Narragansett is verie considerable to this plantation, ffor I doubt wheither [it] be not [sin] in us, having power in our hands, to suffer them to maynteyne the worship of the devil, which their paw wawes often doe; [secondly], if upon a Just warre the Lord should deliver them into our hands, we might easily have men, women, and children enough to exchange for Moores, which will be more gainful pilladge for us than wee conceive, for I doe not see how wee can thrive untill wee get into a stock of slaves sufficient to doe all our business, for our children’s children will hardly see this great continent filled with people, soe that our servants will still desire freedom to plant for themselves, and will not stay but for verie great wages. And I suppose you know verie well how wee shall maynteyne twenty Moores cheaper than one English servant.3

This is, of course, some rather troubling advice. Downing was indeed hoping that they would have occasion for a just war against their Indian neighbors, so that the slaves captured could be traded for more profitable slaves from across the ocean. He doesn’t urge a war to be fought to get slaves, but hoping to profit on the captives of war is a grave thing to commit to paper. As is the suggestion that they can keep twenty Africans for the price of one Englishman, which would be hard to imagine if they were providing equal food and shelter for both.

The Errors

There’s frankly a surprising number of errors in McDurmon’s two sentences. I already mentioned Edward vs Emanuel and Governor vs Deputy Governor. Another is that he misquotes the letter. “The colony” doesn’t appear in the original. Another is that McDurmon refers to “black slaves” while Downing referred to “Moores.” While I don’t want to make an argument out of 17th vs 21st century racial identity, the Moors would be distinct from the “Negroes” – the black sub Saharan African slaves that we would normally associate with the Atlantic slave trade. The Moors were the usually fairer skinned Muslims from Arabia and North Africa.

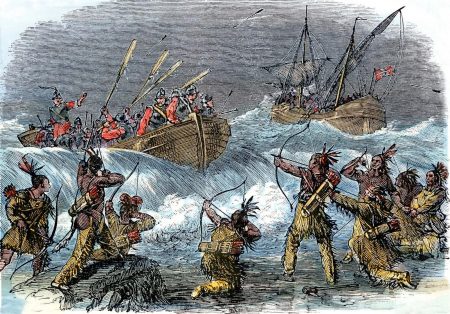

I want to focus on another factual error, which may seem just as minor, but points to a deeper issue. McDurmon told us Downing wanted war with the Pequots, when it was actually the Narragansetts. This may sound insignificant, but for those who know the history of the region, it is a major error. There actually was a Pequot War, the largest war in New England between English and Natives until King Philip’s War in the 1670s. But when this letter was written, the Pequot War was several years in the past, and the Pequots had been effectively wiped out as a nation. On the other hand, at the time this letter was written, the Narragansetts were still a force to be reckoned with. They were clashing with the Connecticut Indians, and the English suspected that they might be forming a conspiracy of multiple tribes to attack the English.4

So did Winthrop take Downing’s implicit advice? Did they attack the Narragansetts to wipe out their idol worship, and gain slaves to trade for Moors? No. There are no extant replies to this letter, but history shows that Winthrop chose a different path. Instead of encouraging an Indian war, he worked to avoid it. The English Puritans were able to maintain the peace for the next three decades until the blood bath of King Philip’s War. They also made decisions that pushed against a reliance on African slaves, particularly those kidnapped as part of the Atlantic Slave Trade. The law of the colony only allowed slaves that were taken captive in a just war, and when a ship called the Rainbow docked at Boston with slaves on board, it was at length determined by the General Court that they were victims of manstealing, not legitimate captives, and thus were freed.5

McDurmon says that Downing’s “comments show the outlook of he elite at least….” It is dangerous to use one man’s statement as evidence of the beliefs of a group, but historians must at some point do that, as the views of most people on most subjects are not preserved. But does the evidence show that Downing’s comments were representative? It does not seem clear they were. As we have seen, there was no Narragansett War in that generation. African slaves were never widely used in New England, and it does not seem that the colony’s leadership made any great efforts to obtain a regular supply.6

The Source of Error

This all is a bit ironic, as McDurmon has set himself up as a bit of an authority on shoddy research and plagiarism, writing and speaking at length on issues in Voddie Bachuman’s book Fault Lines. The way he got mired in all these misstatements in his own book seems pretty simple. He footnotes his quote to a book called In the Matter of Color, which just quotes a few phrases of the letter, and spends about as much space talking about it as McDurmon. That’s also the source of the incorrect name for Emanuel Downing, though not for the incorrect name of the tribe.7

I would argue that it’s quite a dangerous practice to “quote” an original source when you have only read a fragment for yourself. He took a cursory summary from a secondary source at face value and passed along that anecdote he had read, adding in an extra error of his own. He attributes the view of one man to the varied leadership of an entire movement, seemly without knowledge of the historical context and solid analysis of whether that is accurate.

This was one of just a few points in the book where I had knowledge enough to question his statements. I decided to dig into this one, and we’ve uncovered some serious errors and sloppy research. How many more problems would be found if this same treatment was given to the entire book?8

I need to close with a bit of humility here – I’m sure that not everything I have written would stand up to close scrutiny against the original sources, though I am always striving to raise my standards. But perhaps when someone sets themselves up as a writer of history exposing myths, legends and lies, they should take a little more care that they aren’t just peddling a new set from the opposite perspective.

1. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America: An Ethical-Judicial History of American Slavery and Racism by Joel McDurmon (Dallas, GA: Devoted Books, 2019) p. 22.

2. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_colonial_governors_of_Massachusetts.

3. Public Documents of Massachusetts: Being the Annual Reports of Various Public Officers and Institutions for the Year 1903 (Boston: Wright & Porter Printing Co., 1904) vol. xi, p. 220.

4. “New World Rivals: The Role of the Narragansetts in the Breakdown of Anglo-Native Relations During King Philip’s War” by Laruen Sagar (Providence College, 2011) p. 19-21.

5. The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865 by Mark Peterson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), He discusses the Downing letter at length around p. 71 (I only have the audio version). The Rainbow case is also addressed elsewhere. The freeing of the two African slaves is discussed in The Journal of John Winthrop: 1630-1649, Abridged Edition edt Richard S. Dunn and Laetitia Yeandle (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 287.

6. John Winthrop: America’s Forgotten Founding Father by Francis J. Bremer (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 314.

7. In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process, The Colonial Period by A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978) p. 71

8. I haven’t written a comprehensive review of McDurmon’s book, but I published a few notes here.

So interesting. I arrived in New England from old England after WWII. There was one black family in the school district (Wemouth, MA) and I never met any of them. Talk about keeping a low profile. Thanks to all the researchers who fill in the blanks in my historical memory file. Yr posts fascinate me.