In the early 16th century, two cousins grew up near one another in Noyon, France. The name of the oldest was Pierre, and the name of the younger was Jean. Pierre was strong, agile, and muscular. Jean was pale and thin, but there was a spark of intelligence in both their eyes. There was nothing in their outward appearance that would have foreshadowed the fact that these two boys would have an influence felt around the world, and that their writings, examples, and legacies would shape government, religion, and family life for centuries. The boys were playmates in youth, and they were destined to be fellow-laborers in later life.

Still in their youth, both boys were sent to further their education in Paris. Paris was the center of learning, culture, the arts, and the sciences. While Jean took up the honorable study of law, Pierre was trained in a newly developed field of specialty, the field of ancient languages. In the Providence of God, Greek and Hebrew had recently been reintroduced to western Europe by a series of remarkable events. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks had brought Greek scholars fleeing westward with their manuscripts. The expulsion of the Jews by Ferdinand and Isabella had driven Jewish scholars across the Pyrenees mountains with their Hebrew scrolls. These exiles had found refuge in cities like Paris where they were welcomed as teachers. The stage was set for the Protestant Reformation. The Bible was to be the seed, and the fruit of this

seed would change the world.

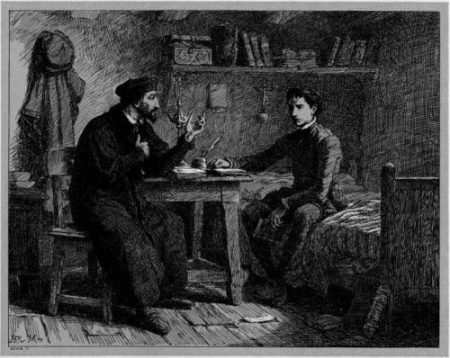

Pierre became very proficient in Hebrew and Greek. The study of the original languages had led him to compare Scripture with the church practices of his day. Very soon, Pierre became a decided Protestant. It was dangerous to be an open Protestant at this period in Paris. Already some bold preachers had been executed for daring to question Roman dogma. But Pierre was not a man to be afraid of threats. He was eager for the conversion of his younger cousin, and went to visit him often in his chamber at Montaigu College.

The great church historian, J. H. Merle D’Aubigne, says of these cousins, “the two youthful Picardins had many long and animated conversations together in which each strove to convert the other.” Jean was alarmed that his older cousin had been bewitched into leaving the old and Catholic faith – the one true religion. Pierre was concerned that Jean was adhering to traditions which had no warrant in Scripture. Jean feared that Pierre was an innovator. Pierre feared that Jean was blinded by man-made rituals.

Jean would later write, “My heart, hardened by superstition, remained insensible to all these appeals.” During the sacrifice of the Mass, Jean would often pray for the conversion of Pierre. And simultaneously, Pierre shut himself up in his chamber and prayed to Christ for the conversion of Jean. Little by little and Scripture by Scripture, the Word of God had its effect upon the heart of Jean. He was converted to the Reformed faith. The name of Jean, or John Calvin has now become known around the world, and his “Institutes of the Christian Religion” became the most articulate and thorough expression of Reformation Doctrine.

While the legacy of John Calvin has enjoyed a well-deserved fame, his cousin, Pierre Robert Olivétan, has been largely overlooked. But he was a worthy man in his own sphere of influence. His accomplishments are many. Long before John Calvin would establish Geneva as the stronghold of Protestantism, Olivétan came to Geneva and prepared the soil for his cousin. He arrived in the city in the spring of 1532 and became the tutor to the sons of Chautemps, one of the members of the Geneva council. Olivétan’s patient teaching of children laid the foundation for the work that his younger cousin would later do in the city. When William Farel later came to Geneva in the fall of that same year, Olivétan stood at his side and defended the Reformed Faith before the leaders of the city. Olivétan’s integrity and allegiance to Scripture won many friends who would have been offended by the raw boldness of William Farel.

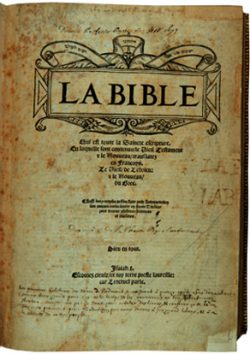

During that winter of 1532, William Farel pressed upon Olivétan the need for a Bible translated directly from the Greek and Hebrew into the French. Olivétan was uniquely qualified for this work, yet he shrank from such a monumental task. “How can I express Hebrew and Greek eloquence in French, which is but a barbarous langauge compared with them?” Olivétan asked. “You know it is as difficult to teach the hoarse raven to sing the song of the nightingale.” But the need was so great that Olivétan set about the work. Thus he was to the French Bible what William Tyndale was to the English Bible. He became a warm friend of the Waldensian pastors and traveled into the Piedmont districts to consult with them and to view their treasured manuscript Bibles as he worked night and day on his new translation.

It was on June 4, 1535 that the work was finally finished. D’Aubigne says that in his humble cottage, Pierre Robert Olivétan was preparing “the great artillery whose formidable volleys were to break down the walls of error.” The poor Waldensian churches were the ones who paid for the first printing and the Bibles rolled off the presses of a converted printer named Wingle. When the work of translation was done, Olivétan wrote these humble words in his introduction. “I have done the best I could. I have labored and searched as deeply as I possibly could into the living mine of pure truth, but I do not pretend to have entirely exhausted it.”

The great work of his life finished, Olivétan packed his bags and moved onward to new frontiers. D’Aubigne says this of Olivétan,

Olivétan was a mysterious personage, a singular reformer. At Paris he called Calvin to the Gospel, and gave him to Christianity as the apostle of the new times. At Geneva, he was the forerunner of his illustrious relative; like a pioneer in the forest, he cut down the secular trees, and prepared the soil into which his pious successor so copiously scattered the seed. He gave to the French Church its first Bible, a translation which so greatly advanced the kingdom of God. He appears only as a precursor of the Reformer, and Calvin had hardly set his foot in this city when Olivétan crossed the Alps, went to Italy, even to the city of the pontiffs, as if he desired now to accomplish a new work, to come to close quarters with the papacy, and prepare Rome for the Reformation as he had prepared Geneva. But there he suddenly disappeared – poisoned as some say. There is a veil over his death as over his life.

Some of God’s servants serve the Lord in the full view of public recognition. Other servants of God, just as faithful, serve in the shadows. Such a man was Pierre Robert Olivétan. But Olivétan’s eternal reward will be great. In fact, much of the credit for Calvin’s work can be attributed to his older cousin, then a mere boy, who prayed earnestly for his relative’s conversion. We sometimes undervalue the work of influencing our own relations, thinking that to serve God we must cross oceans and do mighty and famous deeds. But the life of Olivétan reminds us that the Word of God never returns void, whether it is preached to thousands or spoken to one. A word of truth spoken to a relative in the solitude of a bedchamber has influenced the world eternally for good.

Bibliography

The History of the Reformation by J. H. Merle D’Aubigne