The sound of psalms wafted through the open windows of a country cottage near Bedford, England in 1675. A small group of men, women, and children had assembled together to sing, to fellowship, and to hear the Bible preached. It was no cathedral they were in, and everyone in the room knew that this Nonconformist meeting was illegal. The sound of larks and sparrows took the place of the peals of the organ. Here, there was no high altar, no surplice, no prayer book, no candles, and no stained glass. A simple table served as a pulpit, upon which rested the well-worn Bible of John Bunyan.

Most of these people were farmers, and their faces were tanned just like that of their preacher. This was just the kind of congregation Bunyan loved. It was said of our Lord Jesus, “The common people heard him gladly.” The same could be said of John Bunyan. He was a tinker by trade, a mender of pots and pans, and he spent the week travelling through the countryside with his portable brazier. It was in the countryside, talking to farmers and their wives, that John Bunyan had come to know the common man. He spoke in a direct way that they understood and loved.

But of all the faces in the cottage, a few were dearest. Nearest the pulpit was seated his wife, Elizabeth, and their children. Because of John Bunyan’s many years in prison, Elizabeth had been forced by circumstances to raise the children almost alone. By 1675 Bunyan had already spent 12 years of his life in the Bedford jail. At Elizabeth’s side were arranged the children God had given them. Mary, the oldest daughter, had been blind from birth. Bunyan’s few references to her are always tender, and he called her “my poor blind child.” Sometimes, during her father’s extended imprisonments, Mary had been forced to beg for the sustenance of the family. Her father’s heart ached for this, but as he told his family, “I must venture all with God, though it goeth to the quick to leave you.” On this day, the eyes of “poor blind Mary” were raised to meet her father’s. Her eyes could see nothing physically, but her spiritual vision was very clear.

Little did John Bunyan know that this day would bring him yet another painful separation. As the singing ended, the snort of a horse was heard outside. A party of armed men stomped up the stairs and into the room. The assembled saints kept their seats, and all eyes were fixed, not upon the sheriff and his men, but upon their beloved pastor. John Bunyan looked the sheriff calmly in the eye and announced his text from Luke 23:40, “Dost not thou fear God?” Instead of breaking up the service, the sheriff quietly took a chair. His men did likewise. Bunyan could sense the abiding power of God in the room, and he knew that he must obey God rather than men if he would truly “venture all for God,” Slowly, Bunyan read again his text from the words of the penitent thief on the cross, “Dost not thou fear God?” He read on, “seeing thou art in the same condemnation? And we indeed justly; for we receive the due reward of our deeds: but this man hath done nothing amiss.” When Bunyan looked up from his Bible, he saw the sheriff visibly shaken by the text. The sheriff was holding the warrant for Bunyan’s arrest, but the hand that held the warrant began to tremble. Bunyan knew the power of the Word of God, and he proceeded, “Behold how this man trembles at the Word of God.”

John Bunyan proceeded to preach. He described the wretchedness of man’s sin, the perfect righteousness of the Lord Jesus Christ. Bunyan knew what it was to be a lost and dying sinner. He had once been a man as wicked as the sheriff, a blasphemous, lustful, and proud young man. The text brought to mind Bunyan’s own conversion. He remembered the crushing weight of his own sin. He called to mind the iniquity of his own heart. He remembered the passages of Scripture that seemed to forever condemn him under the righteous judgment of an offended God. He had been terrified by the Scriptures in Hebrews that warned of falling “into the hands of the living God.” He feared that he, like Esau, could find no place of repentance. But he eventually found rest in the same book of Hebrews that pointed the sinner to the perfect righteousness of Christ. He remembered the day that he read the text in Hebrews 12:22, “But ye are come to mount Zion . . . to the spirits of just men made perfect, and to Jesus Christ, the mediator of the New Covenant.” Having realized that sinful men are “made perfect” by the “mediator of the New Covenant,” Bunyan had come to rest in the perfections of Christ and the burden of sin rolled from his shoulders at the foot of the cross.

In his autobiography, “Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners,” John Bunyan relates the agonizing process by which God brought him from sin to salvation, from doubt to faith, from darkness to light, and from defeat to victory. Now, in his sermon, he sought to proclaim the Good News of salvation to farmers and sheriffs alike. If the grace of God could save “the chief of sinners” — Bunyan himself, the same grace could save the sheriff.

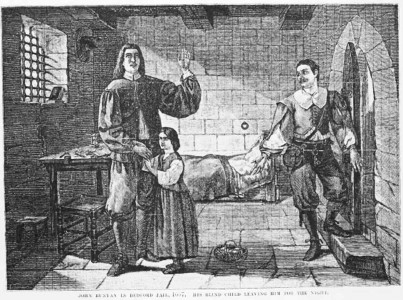

Through the entire sermon the sheriff sat riveted to his seat. At the end the sheriff could not bring himself to bind the man of God. Instead, with great respect, he served the arrest warrant to John Bunyan and told the Nonconformist preacher that he should follow him to the Bedford Jail. Then, the sheriff left the cottage. Bunyan was a free man at that moment. He could have disappeared into the hills. He could have disguised himself. There may have been times when this would have been appropriate. But John Bunyan believed that he should demonstrate before his family and congregation that he was willing to suffer for the sake of the Lord Jesus and that he was not afraid of imprisonment or even of death.

The hardest thing was to be separated again from his wife and children. Elizabeth bravely accepted the bitter separation, yielding her husband once again into the hands of an all-wise God. Blind Mary’s sightless eyes were brimming with tears as she embraced her father, but Bunyan had taught his wife and children that the Christian life demands sacrifice for the cause of truth. He wrote this in his autobiography:

I had also this consideration, that if I should now venture all for God, I engaged God to take care of my concernments; but if I forsook him and his ways, for fear of any trouble that should come to me and mine, then I should not only falsify my profession, but should also count that my concernments were not so sure, if left at God’s feet, while I stood to and for his name, as they would be, if they were under my own care.

Venturing all for God, John Bunyan trusted his family into the care of God and walked freely into the Bedford Jail. In some ways, these months of his final imprisonment were the most important months of his life. It was during these six months of imprisonment that he wrote his most famous and lasting work, The Pilgrim’s Progress. John Bunyan was a tinker by profession and was considered by the clergy of England to be ignorant and illiterate. But from his prison cell, Bunyan wrote a book that has been the world’s best selling book ever written originally in the English language. It’s popularity cannot be explained apart from the fact that men and women see in John Bunyan an honest portrayal of the realities of life.

In many ways John Bunyan’s famous allegory is an extension of his own autobiography. He reminds every pilgrim that the Christian life is never easy. Even after Pilgrim’s sins rolled away at the foot of the cross, there were struggles and hardships in life. Doubting Castle looms big, and Giant Despair is very real. Doubts, fears, struggles, darkness, and sorrow are just as much a part of the Christian’s life as victory. Apollyon must be met and conquered. But through all of life’s journey we are guided and sustained by the hand of a gracious God, and we can look back to say, “All things work together for good to them that love God” (Romans 8:28).

John Bunyan reached the end of his own pilgrimage in 1688. His faith was put to the final test as he came to the brink of the River of Death. “Jesus, the mediator of the New Covenant” had sustained him in life, and was there again to sustain him in death. Bunyan had recorded in The Pilgrim’s Progress how that when Christian and his companion emerged from the river, they were met by two shining ones with this triumphant message, “Ye are come unto Mount Zion, the city of the Living God” (Heb 12:22). The life of John Bunyan encourages us that the glories of the Celestial City await every sincere Pilgrim who will truly venture all for God.

Bibliography

Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners by John Bunyan

The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan

Venture All for God: Piety in the Writings of John Bunyan

Christian History in First Person video lectures by Dr. Edward Panosian