The election of 1800 was one of the very tumultuous ones in American history. Due to a mistake in the Constitution that was later corrected, one of the electors had to vote not vote for their party’s candidate for vice president, or there would be a tie inside the party. A problem was bound it come, and it happened in 1800, when Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr received the same number of electoral votes, so the election was sent to be resolved in the House of Representatives. For weeks the struggling continued, as Burr tried to leverage this mistake in the process to gain the presidency.

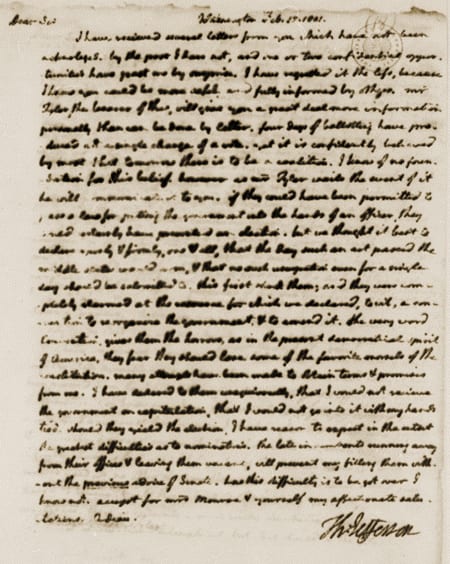

At one point, as negotiations continued, civil war was even discussed by Jefferson in this letter:

Washington, Feb 15, 1801.

Dear Sir,–I have received several letters from you which have not been acknoledged. By the post I dare not, and one or two confidential opportunities have passed me by surprise. … Mr. Tyler, the bearer of this, will give you a great deal more information personally than can be done by letter. Four days of balloting have produced not a single change of a vote. Yet it is confidently believed by most that to-morrow there is to be a coalition. I know of no foundation for this belief. However, as Mr. Tyler waits the event of it, he will communicate it to you. If they could have been permitted to pass a law for putting the government into the hands of an officer, they would certainly have prevented an election. But we thought it best to declare openly and firmly, one & all, that the day such an act passed, the middle States would arm, & that no such usurpation, even for a single day, should be submitted to. This first shook them; and they were completely alarmed at the resource for which we declared, to wit, a convention to re-organize the government, & to amend it. The very word convention gives them the horrors, as in the present democratical spirit of America, they fear they should lose some of the favorite morsels of the constitution. Many attempts have been made to obtain terms & promises from me. I have declared to them unequivocally, that I would not receive the government on capitulation, that I would not go into it with my hands tied. Should they yield the election, I have reason to expect in the outset the greatest difficulties as to nominations. The late incumbents running away from their offices & leaving them vacant, will prevent my filling them without the previous advice of Senate. How this difficulty is to be got over I know not. Accept for Mrs. Monroe and yourself my affectionate salutations. Adieu.

View this letter at the Library of Congress.