The Mexican-American War, lasting from 1846 – 1848, was one of America’s shorter and less costly wars. The United States soldiers disastrously defeated the Mexican army, capturing Mexico City and winning a complete victory in the peace treaty. But why was the Mexican War fought? Was the United States in the right? How do these principles apply to the nation today? This essay will examine these questions.

The Mexican-American war, at the time it began, was simply the next step in the territorial disagreements between the two countries. The United States had annexed the Republic of Texas, which had declared itself independent from Mexico, but Mexico refused to acknowledge it. A border conflict between the armies was inevitable, and that fighting soon brought on full scale war. But the roots of the conflict go back a decade to the Texas Revolution, and the annexation of Texas the year before, for who was right on those issues really determined whether the Mexican American War was just. If Texas was part of the United States, America had every right to defend it. But if it had been stolen from Mexico, the United States was in the wrong.

In the early 19th century the philosophy of Manifest Destiny was common in America.1 It held that it was “our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”2 When Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, it opened up immigration into the mostly unpopulated land of Texas. Many Americans went there, driven by the urge to spread west across the continent, even though it was not part of the United States. Many came from the southern states and brought slaves with them. Before long the Mexican government found that part of their country had begun to look very much like the United States. They tried to backtrack on some policies, outlawing immigration from the United States and banning slavery. The Mexican government was unstable, and President Santa Anna dissolved the Congress and created a military dictatorship. Several Mexican states declared their independence from his rule. The American settlers in Texas did the same, publishing a Texas Declaration of Independence. It was patterned after the United States Declaration of Independence, and gave a list of reasons why they believed they had a right to independence.3 In evaluating whether this was right or not, it is certainly true that most of the American immigrants had little love for the Mexican government, and many wished all along to be part of the United States. Some in the United States supported the revolution as a way to gain more land, as they hoped to eventually annex the new nation. But on the other hand, the Texans did have valid grievances.

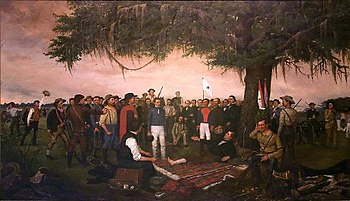

The Texas Revolution began in 1835, and within six months they were victorious. Mexico was defeated, but they did acknowledge the independence of Texas. For nearly a decade, Texas remained an independent republic. Although they had thrown off Mexican rule, the settlers wished to be part of the United States. In 1845 the United States government accepted a proposal for annexation by the Texan government. With Mexico still claiming Texas ground as their own, the conflict soon escalated. They determined to fight for the southern portion of the modern state of Texas, which they said historically had never been part of that province. When US soldiers moved into the disputed area, the Mexican-American War broke out.4

The Americans were too eager to spread across the continent and did not care enough for the claims of other nations. But they were right when it came to the Mexican War. Their attitude may have been wrong, and at many points along the way they could have been much more willing to listen to the arguments of the Mexican government. But Texas had a right to declare their independence, the United States could legally annex Texas, and they had the right to fight a war to protect it.