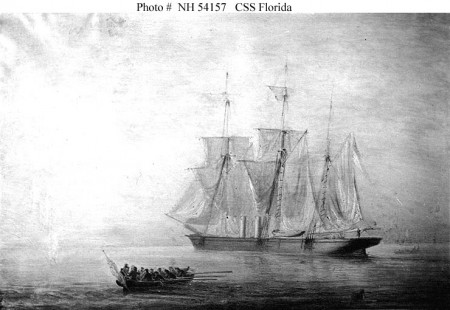

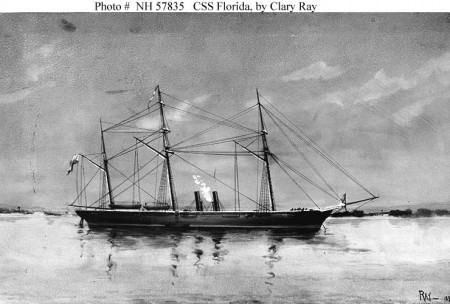

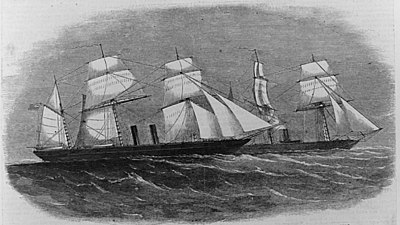

The most famous of the Confederate commerce raiders was the CSS Alabama, but it was far from the only one. There were many ships that sailed the world under the Confederate navy jack, and another very successful one was the CSS Florida. She was built in Liverpool, England for the Confederate government, and was launched in 1862. But the English, as neutrals, could not legally build ships for the Confederacy. This problem was avoided by launching the ship without her weapons, and then turning her into a warship at sea.1 The ship that would become the Florida was first called the Oreto, and it was built alongside the 290, which would become the CSS Alabama. The Oreto left England on March 22 and sailed to the Bahamas. There she was to meet a tender and be turned into Confederate raider. On the journey across the Atlantic she was shown to be a good sailor. The Confederate agent on board wrote, “I do not think there is a stronger vessel of her class afloat….”2 But as she waited in Nassau harbor, word was received that the American government was trying to convince the British customs officers to seize the Oreto. She was actually searched, but they could find no reason to impound her as a warship. Eventually the Bahama arrived, carrying men and supplies for the soon to be Florida. Twelve United States men of war also came into port, and they were certain to try to capture a Confederate ship.

The Confederates waited, hoping their plan would not be discovered, until Lieutenant John Newland Maffitt, the man destined to command the ship, arrived in the harbor. Maffitt had been an officer in the US Navy, but when he came to Bermuda he was in charge of a blockade runner. He was given command of the Oreto, or the Manassas as she was also called, as the only Confederate navy officer available. But since officially she was still a private vessel he could not take possession of the ship, and could only secretly instruct her civilian captain. He wrote to the secretary of war, “I have presonally assumed command of the Manassas, which vessel I hope to have ready for service soon, and my whole soul will be devoted to giving éclat to our cause and annoyance to the enemy. My difficulties are great, my ambition greater.”3 Before she could get away, Captain McKillop of the British Vice-Admiralty took possession of the ship as a lawful prize. But within a day the Queen’s Attorney on the island ordered that the ship be released. It was nearly certain she would be armed, but as she as not yet, it was illegal to seize her. But then she was seize yet again by the British. On June 5, 1862 she went into the Court of Admiralty to decide what should be done with her. The case opened a month later, and for six days the arguments continued over whether she could be charged. While waiting, John Maffitt wrote to his daughter, “I shall be painfuly distressed if this grand chance is lost to us, but the entire affair was badly managed on the other side of the water.” Finally on August 7th the vessel was declared free. Maffitt took command, and that night ran her out of the harbor with a skeleton crew before any anyone again tried to seize her. A schooner was sent back to Nassau to pick up her guns and cargo. Hard work had to be done in the hot sun to load these on board, and the wardroom steward died from it. The job was finally completed and the ship was commissioned the Confederate ship Florida on August 17, 1862.

Any hopes of striking the Union commerce were dispelled even before her outfit was finished. Yellow fever struck the ship, and ran rampant among the crew. There was no doctor on board, so the captain had to fill that role himself. In just five days only five men were well. The ship was useless in such a condition, and Maffitt ran her to Cuba, where he came down with the sickness himself. Yellow fever is a truly terrible disease. Only a few hours after James Maffitt first showed symptoms he was completely incapacitated, and for seven days he could remember nothing in what he called “an epoch of horror and suffering that can not be realized save by those who have been the recipients of this fell desease.”4 When he came to, he found the doctors did not think he would recover. When one expressed some hope, the Lieutenant “told him his prognostics were correct, as I had not time to die.”5 No new sailors could be found there, and there were not enough officers on board. With the cruise turning out to be a disaster, Maffitt chose to run to Mobile, Alabama. Somehow he was able to make it there even with the condition of the crew.

He found the Union navy, tasked with blockading the port, blocking his way. His crew could not fight, not only did they lack the manpower, the equipment for their guns had not been loaded in the hurry to escape Nassau. So Maffitt ran up the Union jack, and sailed towards the entrance to the harbor. This common practice did not deceive the Federals, and their three warships came out to meet her. Onward the Confederate sailed, soon hit with the accurate fire of the three Federal vessels. One tried to cut her off, but the Florida kept on straight, so the northern ship pulled back to avoid a collision. Although the Florida was hit many times, after twenty minutes she was able to safely come to rest underneath the Confederate guns. Stephen Mallory, the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, complemented the sick Maffitt on his handling of the ship, saying “I do not remember that the union of thorough professional skill, coolness, and daring have ever been better exhibited in a naval dash of a single ship.”6

Safe in a friendly harbor, Maffitt was able to recover from his sickness, recruit a new crew, and prepare the ship for a cruise. After three months of slow preparations, the ship ready for combat. The problem was now how to get out past the blockading fleet. As he prepared to try to make his esacpe, Maffitt wrote in his diary:

‘Tis to the interest of the Confederacy that we get out intact, as my orders are to assail their commerce only, that the mercantile part of the Northern community, who so earnestly sustain the war by liberal contributions, may not fatten on its progress, but feel all its misfortunes. As the Alabama and Florida are the only two cruisers we have just now, it would be a perfect absurdity to tilt against their more than three hundred, for the Federals would gladly sacrifice fifty armed ships to extinguish the two Confederates.

When a man-of-war is sacrificed ’tis a national calamity, not individually felt, but when merchant ships are destroyed on the high seas individuality suffers, and the shoe than pinches in the right direction. All the merchants of New York and Boston who had by their splendid traders become princes of wealth and puffy with patriotic zeal for the subjugation of the South, will soon cry with a loud voice, peace, peace; we are becoming ruined and the country —-ed!7

Knowing they had a dangerous ship cornered, the Federals had increased their forces off Mobile.

The Florida was far to weak to take them head on. The Confederates painted the Florida a dark color, and waited for a gale to cover their exit from the harbor.

Early on the morning of January 16th, 1863, Maffitt saw his opportunity. Running out of Mobile, he was in the center of the Union fleet before he was spotted. The Federal ships gave chase, but over the next day the Florida was able to outrun or elude all of them. She quickly entered on her mission of commerce raiding, capturing and burning her first prize on the 19th. She had to stop in at Havana, Cuba, as the her coal was found to be bad, but she made off the next day before the Union ships could close on her. She continued sailing off the coast of South America and the West Indians, capturing the American merchantmen. In February Maffit stopped in Barbados for coal, after convincing the governor to ignore the requirement of three months between stops in a British port. One of the largest ships she captured was the Jacob Bell, which carried a cargo of tea worth $1-2 million. Along the way he had to avoid the US Navy ships sent after him, running away from one, and avoiding another while disguised as a merchant.

In early May the Florida sought anchorage in Brazil harbors to repair her engine and take on food. But neutral countries would only allow Confederate ships to stay for twenty-four hours to take on vital supplies, especially since the raider was carrying prisoners and cargo from Union ships. Maffitt protested that the refitting would take four days, and said that by giving only twenty-four hours Brazil assumed “the responsibility of ejecting a disabled and distressed vessel of a friendly power upon the ocean, an act that would receive the condemnation of all civilized powers….”8 With this the governor of Pernambuco relented, and allowed him into the harbor.

In May, Maffitt was promoted to Commander for his “gallant and meritorious conduct in command of the steam sloop Florida, in running the blockade in and out of the port of Mobile, against an overwhelming force of the enemy, and under his fire; and since, in actively cruising against and destroying the enemy’s commerce.”9 On July 8th the USS Ericsson, a side-wheel steamer, approached the Florida. The poor quality of the coal the Confederates had on board prevented them from escaping, but a broadside from her guns chased the Union ship away. When the Florida put in at St. George’s, Bermuda a few days later, she exchanged salutes with the British forts. This is something the commander of the forts should not have done, as Great Britain did not recognize the Confederacy as a nation. He was later rebuked by his government in London, and it was the only time a Confederate vessel was saluted by a foreign military.10

At the end of August the Florida put into Brest, France for repairs, as they had visited an English port within the past six months and so could not visit another. After months of rigorous cruising, Maffits health had broken down. He turned his command over to Lieutenant Charles Morris. The seamen of the Florida liked Maffitt as their commander, because of his “kindness and consideration,”11 and asked to be transferred with him to whatever ship he was given next. This probably did not occur. Maffitt returned to the Confederacy, and was given command of the CSS Albemarle.

Morris left Brest in February 1864, and sailed out on another successful cruise. Over the next seven months he captured 13 ships from the Union in the Atlantic ocean. The beginning of the cruise was hampered by the three assistant engineers, who were sickly and incompetent. The ship spent time in Bermuda making repairs and waiting for replacement engineers to be sent out from the South. She later captured a steamer that could have been turned into a commerce raider, but she had to be sunk because there were no engineers to send on her. She put in to Bahia, Brazil on October 4, 1864 to procure provisions and made some minor repairs. While these were being made, Morris allowed half the crew to go on shore in three hours shifts. The USS Wachusett, under the command of Napoleon Collins, came into the harbor the next day. The United States sent a letter to the Florida, by a gentleman of the name of L. de Videky, offering a challenge of battle once the repairs were completed. But the Confederates refused the letter, as it was addressed to sloop Florida rather than the CSS Florida. The American would not send the later, as that would be an implicit admission of the sovereignty of the Confederate States. He sent the letter again, but had the bearer read it before delivering it. That way Morris could refuse it, but still give an answer. The Confederate said that he would not seek or avoid conduct with the Wachusett, and would endeavor to destroy her once they were outside the waters of the neutral Brazil.12

Morris made the mistake of going ashore with half his crew, even though there was an enemy in the harbor. He was awoken early on the morning of October 7th at the hotel where he was staying, and told there was commotion around the Florida. Getting up, he discovered that the Wachusett had captured the Florida, and was hauling her out of the harbor. The Union ship went out to attack at 3:15 am. The Confederate watch sighted her, and when she did not answer a summons sounded the alarm. Before the raider’s crew could assemble the Florida was rammed by the Washusett. The Florida sustained significant damage, with her mizzen-mast and main yard broken. Collins pulled his ship back, expecting the rebel vessel to sink. The Confederates fired a few shots with what pistols and muskets they had on hand, and the Federals poured in a volley from their muskets and a few cannon. The Washusett pulled back and demanded the Confederate’s surrender. When the rebels refused, the Unions fired several more times into the ship. Finally Lieutenant Thomas Porter surrendered the ship. She was in a hopeless position – badly damaged, without her steam up or even shot in her cannon. When the crew heard Porter surrendered, a handful jumped overboard, prefering to trust themselves to the water rather than the mercies of the Yankees. Some of them escaped, but most were shot in the water by the Union sailors. Five Confederates were killed in the fight, nine wounded and seventy captured. Just three Union sailors were wounded.13

This attack was illegal, as it was carried out in a neutral harbor. The Brazilian forts fired a few shots at the Wachusett as it towed the Florida out to sea, and sent out a sloop in pursuit, but they were unable to stop her. Mr. de Videky, who had delivered the American consul’s letter to Morris, wrote the Confederate in apology when he heard what had been done. “How could I think such villainy to be possible?” he wrote, calling it an “infamous, blackguardly trick.”14 Commander Collins had been given permission by his commander to attack the Florida even if it was in a neutral port, as long as the guns of the harbor forts were not too powerful. At first the government supported his actions, but upon the protest of the Brazilian government, they court-martialed Col;lins on charges of “violating the territorial jurisdiction of a neutral government.”15 This trial was held in early 1865. Collins pleaded guilty, but said he had done it for the public good. The court found him guilty, and sentenced him to dismissal from the navy. This sentenced was not approved by the government. What Napoleon Collins had done was in accordance with his orders, and it made him a hero. After the trial was held to appease Brazil, Collins was promoted in 1866 to captain. The United States government was willing to violate the rights of a neutral if they could destroy one of the fearful commerce raiders which had destroyed much northern shipping, and tied up many naval resources in pursuit.

The CSS Florida was taken to Hampton Roads, where it arrived on November 11, 1864. She was badly damaged on November 24, when she collided with a troop transport, and she sunk four days later. It is very possible that this sinking was not an accident. Her sinking solved the possibility that a court case could declare her capture illegal, and require that she be returned to the Confederates. According to notes found by his wife after his death, John Maffitt met with Admiral David Porter in 1872, and Porter told him the true story of the sinking. He said that the government in Washington expressed the wish that the ship was sunk, so under his orders the hull of the Florida was filled with water, and the ship allowed to sink.16 Whether the story is true or not, it was without a doubt very convenient for Washington. It would have been better to intentionally sink her than have her go over to the enemy.

1. The Civil War at Sea by Craig Symonds (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012) p. 84.

2. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, p. 758.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid, p. 765.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid, p. 761.

7. Ibid, p. 769.

8. Ibid, vol. 2, p. 647.

9. Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904) vol, 3, p. 356.

10. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, p. 650.

11. Ibid, p. 661.

12. Ibid, vol. 3, p. 631-632.

13. Ibid, p. 255-256, 632, 637.

14. Ibid, p. 644.

15. Ibid, p. 268.

16. The Life and Services of John Newland Maffitt, by Emma Martin Maffitt (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1906) p. 387-388.

Good article, I like the CSS Florida a lot.

Yours, Caleb Sides.

Thanks!