There have been many times while deep in research, that I have found myself scanning a historian’s account, searching for a quote from the primary source, even if it is just a phrase, that I could paste into Google to find the full source so that I could ignore that historian and his carefully crafted account – cutting out the middle man between me and the “true story” of what occurred. I wonder how many times this is because in the books I was reading the historians had unnecessarily inserted themselves between their readers and the historical facts.

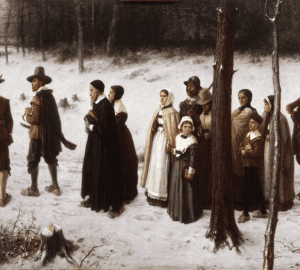

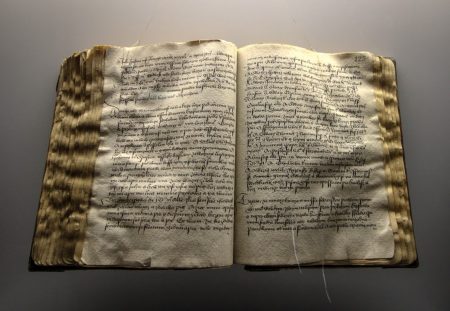

In my current research on the Pilgrims, there are many parts of that story that have been told and retold hundreds of times by hundreds of historians for which there are only one or two primary sources. Across all historical writing, there are countless examples of this. An experienced reader will often get the sense, aided by a rough understanding of the sources available from a particular time period, that their historian of choice is just rewriting the one source available for a particular anecdote. I often find that as I read the different historians’ accounts, I just begin to have more and more appreciation for the original source. As you become more familiar with the primary sources, you notice which of the things those historians say are just their own speculation. You notice when they simply make things up. You notice the things that they leave out that maybe you think are actually pretty helpful. You begin to notice that in many cases, the historian has arguably done no better job of describing exactly what we know about what actually happened than the primary source did.

There are times when we do need a historian’s retelling of an event. Sometimes the subject they are studying is so embedded within columns of numbers and tables of data that it takes remarkable erudition to turn it into a readable narrative. Other times the subject is one like, say, a battle in World War II, where there are a large number of first person accounts, and some that are quite eloquent, but it takes a historian’s labors to synthesize them all into a broad story. Sometimes there is only one source, but bias of the original teller is so pronounced that it requires the historian’s hand to untwist the truth out of his imprecations. There are other times when the source is written in such dull language that it would put the reader to sleep instead of bringing them to the edge of their seats.

Yet while there is a time and a place for a good story well re-told, I would argue that historians are too quick to restate a primary source when they should let them sing for themselves. Give some context before and some commentary and beefing up afterwards, but let the historical evidence stand on its own legs. It may make your book or article less unique, but I’d argue that your readers and history in general would be better served if you spent your time and eloquence elsewhere, where they are really needed.