In the last issue, we considered the life of Latimer. We turn now to the life of Ridley, Latimer’s faithful companion at the stake, and the man to whom Latimer addressed his final sermon, “Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as I trust shall never be put out.” In this issue, we shall see how Master Ridley did indeed stand firm in the fire and “play the man.” But first we will consider Ridley’s background and the steps that brought him to the fire.

Nicholas Ridley was born in 1500 in the extreme north of England, very near the Scottish border. The Ridleys were an ancient house of knights whose bravery was known and admired throughout the border country. They could meet an enemy with calm courage, keep their heads in the heat of battle, and endure pain without flinching. These qualities would be seen in Nicholas Ridley, but he was a knight of a different kind, a knight who wielded the Sword of Truth with unflinching courage. He was resolved to win the victory, though he must die an agonizing death.

Like Latimer, the man who became his close friend and example, Nicholas Ridley went to Cambridge University where he came into contact with other young students like John Rogers, Thomas Bilney, John Bradford, and William Tyndale. These became known as the “Scripture men,” and they met in the White Horse Inn to study and discuss the Bible.

Since the Ridley family was a family of influence and wealth, they sent Nicholas to the continent to study. Thus, unlike the other English Reformers, Nicholas Ridley had experience in the University of Paris. Among the Doctors of the Sorbonne, Ridley was sickened and saddened by the lack of knowledge of Scripture. He wearied of reading the Medieval Scholastics and longed for the pure fountain of God’s truth. The steps of Ridley’s conversion are not known. He was not converted in a moment, like Hugh Latimer or Saul of Tarsus. His conversion was slow, gradual, but just as sure. We know from his writings that he began, in the halls and gardens of Cambridge, to commit large sections of Scripture to memory. What the sword was to the ancient house of Ridley, the Bible was to be to Nicholas.

The English Reformation did not gush forth from the earth like a geyser. Rather it grew slowly and steadily, just as the melting snow on a mountainside descends into the valleys where it forms creeks, then streams, then a mighty river that rolls silently and slowly along with resistless power. So grew the English Reformation.

A brief discussion needs to be made of the relative usefulness of Cranmer, Latimer, and Ridley, the three great martyrs of Mary’s reign. Cranmer was a wise leader who used his gentle ways to win friends to the cause of Reform. Latimer was an eloquent speaker who used his tongue to proclaim verbally the truth of God. Ridley was a careful writer who used his pen to write clearly the defense of the Reformed Cause. Though Ridley was the junior of the three men, the other two leaned upon his writing.

The great question at stake in the English Reformation was the question of Transubstantiation. For a long time, even Cranmer held to the belief that, somehow, the Real Presence of Christ must be in the elements. It was not an easy thing for a Bishop of the church to challenge and overturn centuries of tradition. It was Ridley whose masterful examination of the subject convinced Cranmer and Latimer that the Mass must be entirely rejected, not only as unbiblical, but also as blasphemous, idolatrous, and dangerous. Ridley read the continental Reformers like Zwingli, and he drew on Zwingli’s writing to form his own position.

Nicholas Ridley was recognized by his friends as the intellectual leader of the English Reformation. He had a mind that retained all it was given, and his memory was remarkable. He studied for several hours each day and was an active reader whose conversation delighted and edified all that came to stay with him in his parsonage. He was a warm and generous host, and nobody ever came away from his home without being edified by the friendship.

Along with Latimer and Cranmer, Ridley knew that he would not long survive Mary’s reign. After the death of Edward VI, Ridley gave strong support to the coronation of Lady Jane Grey. When she and her young husband went to the block, Ridley was a marked man from the very start of Mary’s reign. Notwithstanding his knowledge of her hatred of him, Ridley went to greet Mary and even offered to serve her and hold services for the royal court. This request was turned down.

For his support of Lady Jane Grey, Nicholas Ridley was arrested on the charge of treason, but the charge was changed to a religious one and he was eventually tried and executed for heresy. Long debates failed to move him an inch from his position. Like his ancestors, Ridley would not flinch in the public arena, and many intellectual lances were shattered against his shield. When the formal trial was made, Ridley had the audacity to put his cap on his head whenever the Pope was mentioned. When Ridley was charged with denying the validity of the Mass, he replied calmly and clearly, “Christ made one perfect sacrifice for the sins of the whole world, neither can any man reiterate that sacrifice of His.” So the debates continued. John Foxe, who was a personal friend of Ridley’s and served under him as a deacon, said that, in spite of the most earnest arguments of the Papists, “nevertheless Ridley was ever talking things not pleasant to their ears.”

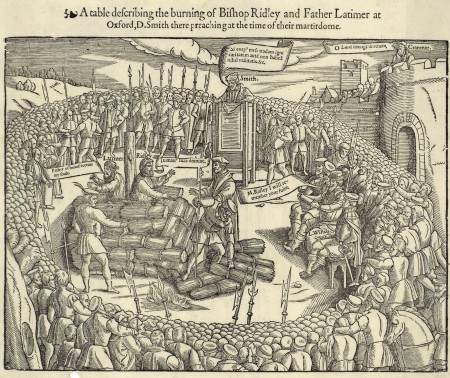

On the day of his execution, Nicholas Ridley dressed in his best attire. While Latimer wore a plain and simple gown, Ridley dressed in a black gown trimmed with fur and velvet. This was not to be proud or showy. Ridley was from an ancient house of knights, and he was going out to his final victory. While Latimer tottered because of age and infirmity, Ridley walked firmly and boldly to the stake. When questioned if he would recant, Ridley said, “So long as the breath is in my body, I will never deny my Lord Christ and His known truth.”

Ridley then gave away all his fine garments and stood in a plain undergarment. As the smith chained him to the stake, Ridley said, “Good fellow, knock it hard, for the flesh will have its way.” Nicholas Ridley did not want the intense pain to make him flee the stake. The hour of his final battle had come. As the faggot was lit and laid at the feet of the two men, there was perfect silence in the air as the tension mounted. As the flames began to leap upward, Latimer broke the tense silence with those immortal words, “Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man.”

As the fire blazed up, the wind blew the fire to the side of “Old Father Latimer.” Latimer looked upward and said peacefully, “Father of heaven, receive my soul.” He soon died with little apparent pain. It would not be so with Ridley. He would indeed have need to “play the man.” The wind blew the fire hard to Latimer’s side, and the fire on Ridley’s side was badly made. The green wood on top would not catch fire, but the wood at the bottom burned fiercely. While Ridley’s face and body were unharmed, his legs were almost burned away. All this time, his shirt was not even singed. He involuntarily leaped up and down in the fire as the burning flesh and muscles reacted to the pain, but he would not utter a scream or cry of reproach. John Foxe says, “Even in this torment, he did not forget to call on God, saying ‘Lord, have mercy on me.’” A relative of Ridley’s tried to relieve his agony and piled more wood on the fire. This only worsened the problem, and Ridley suffered on, but he “played the man.”

Finally, one of the guards realized the problem and reached forward with the hook at the end of his halberd, pulling away the topmost wood. The fire blazed upward through the wood. Ridley cried out in Latin the words he had learned long ago, “In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum.” But then, as though he remembered that he was an Englishman, and that the Bible was now in the hands of the common man, he repeated the prayer in his native tongue, “Lord, receive my spirit.”

The candle that was lit by Latimer and Ridley that day is still burning brightly. If you hold an English Bible in your hands, if you sing hymns from an English hymnal, if you worship God in Spirit and Truth, then you owe these men a debt of gratitude. Truly, they did light a candle that has never gone out. That shining candle is now entrusted to us. Don’t let it be extinguished. Don’t compromise the Word of God. Don’t give up the truth for which these men died. Even if you too must burn for it, remember Master Ridley and “play the man.”

Bibliography

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs by John Foxe

Masters of the English Reformation by Marcus Loane

The History of the Reformation by J. H. Merle D’Aubigne