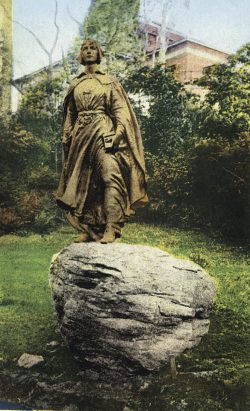

If a visitor today to Plymouth, Massachusetts has the patience to seek out a quiet corner of Brewster Gardens, near the banks of the old Town Brook, he will be rewarded to see among the trees and flowers a monument dedicated to the “Maidens” of the Mayflower. The monument consists of a copper statue of a girl looking bravely forward into the future, a Bible in her hand and hope in her eyes.

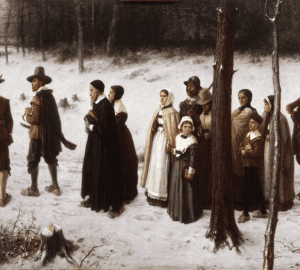

We know very little about the handful of young girls that left their secure homes in England and the Netherlands to cross an unknown ocean establish a new home in the wilderness. Because only four adult women survived the first winter, much of the labor and toil of Plymouth Colony fell upon the inexperienced shoulders of the younger girls.

One “Maiden of the Mayflower” was a seventeen-year-old girl named Priscilla Mullins. Her father was William Mullins, an English shoemaker and businessman from Dorking in Surrey. The Mullins family were not members of the Leyden Congregation, and they were thus among the “Strangers” aboard the Mayflower. They did not board the ship in the Low Countries but were part of the contingent from London who joined the expedition on the coast of England.

Seventeen would be a very difficult age for a girl to leave her home and venture with her parents into a howling wilderness. Priscilla was at the age when most girls of her generation were considering marriage, and it would have been very obvious that the pickings would be few in the New World. It would have been much easier to remain in England where the number of prospective husbands was much greater, and where she was already comfortable.

Priscilla had already lost her mother as a little girl. William Mullins had remarried a lady named Alice, who joined him in the venture to the New World. While William left his two eldest children behind in England, he took Priscilla and her fifteen-year-old brother, Joseph, along with him. Thus, the Mullins family consisted of Priscilla’s father, William, her step-mother, Alice, Priscilla herself, and her younger brother, Joseph. Also traveling with the family was an apprentice named Robert Carter. Shoes are an important commodity in any wilderness colony, and William Mullins carried a good stock of sturdy shoes and boots with him which later proved to be very useful in the New World.

The entire Mullins family survived the stormy voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, and the name of Mr. William Mullins appears as a signer of the Mayflower Compact. During the first difficult winter at Plymouth Colony, the Mullins family at first escaped unscathed. Many of the other families lost at least one, but the Mullins did well until the father, William Mullins, became very sick during the last few days of February, 1621. His condition worsened, and he wrote a hasty will that was committed to the care of Governor John Carver. After a short sickness, Mr. William Mullins died on February 21, leaving a widow and two orphaned children.

It is never easy for a girl to lose her father, but for a Priscilla to lose her father at such a time, when she was just blossoming into womanhood, would have been very difficult indeed. But tragedy followed tragedy, and the worst was not yet over for Priscilla. The family apprentice, Robert Carter, followed his master to the grave. Even as the weeks of spring crept on and the casualties began to diminish, Priscilla lost her stepmother, Alice. Sometime during that summer, she stood with tearful eyes over the grave of her brother, Joseph, leaving her the lone survivor of her family.

Many girls in her situation would have given up all hope of life in such a harsh frontier, and would have sought the first opportunity to return to comfortable England and sought refuge with her older brother and sister. Courageously, Priscilla Mullins decided to stay in Plymouth, where her father lay buried on Cole’s Hill. As the lone survivor of her family, she resolved that she would not give up.

One incident in the life of Priscilla Mullins has been made famous by the poem of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “The Courtship of Myles Standish.” In the poem, Captain Myles Standish, having lost his first wife in that same General Sickness, is said to have fallen in love with young Priscilla. Too bashful to make his romantic interest known, he sent his friend and roommate, a young cooper named John Alden to make the request for him. When John Alden finally spoke to Priscilla Mullins, she is supposed to have given the reply, “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?” suggesting that John Alden was also in love with one of the very few girls of marriageable age in the colony.

Although this romantic story is often dismissed as a mere fable of a poet, there are some things that give credence to the story. Longfellow was himself a descendant of Priscilla, and a collaborating written record has surfaced that suggests that Longfellow may have been passing along an oft repeated family story that was indeed based in fact.

Whether Myles Standish sought the hand of Priscilla or not, she did opt to marry the young but poor cooper named John Alden. John Alden was also a “Stranger,” a young man brought along for his skill as a cooper rather than for his adherence to the Separatist church.

John Alden and Priscilla Mullins were married in what is presumed to be the fourth marriage in Plymouth Colony. They eventually settled in Duxbury, to the north of Plymouth, where their homestead has recently been discovered. Interestingly, John Alden and Myles Standish remained close friends throughout their lives, and raised their families together. They rest together in the same cemetery in Duxbury, awaiting the resurrection. In a beautiful close to the supposed romance, the son of Myles Standish married one of the daughters of John and Priscilla.

The character of young Priscilla Mullins lived on in her descendants. This brave young “Maiden of the Mayflower” who would not give up and go home went on to become the mother of a multitude, many of whom held important posts in church and state. She and John Alden had ten children, dozens of grandchildren, and hundreds of great-grandchildren.

John Adams and John Quincy Adams were both direct descendants of Priscilla Mullins, the girl who would not quit. In spite of losing her mother, her father, her step-mother, and her brother, she cast her lot here on the rugged shores of the New World and place her hope and trust in the promises of a faithful God. Priscilla’s faith, her determination, and her courage give us an inspiring legacy, and we must pray that a new generation of young girls will rise up and follow her noble example.