A farmer and his young wife bowed low over the grave of their infant daughter. Their tears fell softly as they sought to be a comfort to each other in their mutual sorrow. Infant mortality was very high in Colonial America, and almost every family knew the severe heartbreak of laying an infant into an early grave. These bereaved parents were David and Martha Davies. Their family roots were in Wales and they lived on a small farm in the colony of Delaware. Neither David nor Martha had much education, and they still spoke the language of their native Wales. They signed their names with an X on the confession of faith of their Welsh Baptist Church, but made up for their lack of formal education by a firm faith in God and a commitment to hard work by the sweat of the brow. David Davies built a substantial two-story brick home that still stands today after three centuries.

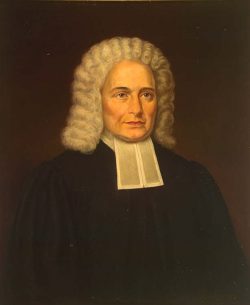

But David and Martha would give to the world a more enduring legacy than a colonial farm and sturdy brick house. They began to pray to God that he would grant them another child to glorify Him in this world. They waited for five long years. Finally, on November 3, 1723, Martha gave birth to a son. Inspired by the story of Hannah from the Old Testament that prayed long for a child, Martha named her son Samuel, meaning “asked of God.” Although the education of the parents was limited, their son would one day be the President of Princeton University, a scholar admired on both sides of the Atlantic, and one of the most faithful pastors and eloquent preachers to grace an American pulpit.

Samuel lived the life of a typical farm boy. He helped his father in the fields and he learned to hunt deer and squirrels in the woods and to go crabbing and fishing at the nearby Atlantic Coast. His mother ensured that her son learned to read in his youth, and he was sometimes found reading his books or teaching other boys to read in the fields and forests. When Samuel was eight years old, his parents left the Welsh Baptist church and started attending a local Presbyterian church. With no good English schools in the area, David and Martha sent their young son Samuel to be educated at a boarding school in New Jersey. It was much like the sacrifice of Hannah who sent her son Samuel to live and serve with Eli the priest. Like Samuel under the care of Eli, Samuel Davies did not have good influences at his grammar school. The pastor of Hopewell Presbyterian church he attended was charged with immorality and drunkenness. But Samuel was sustained by the prayers of his pious and faithful parents.

The winds of revival were beginning to sweep over colonial America. In 1734, when Samuel was 10 years old, Jonathan Edwards had seen the Holy Spirit of God moving in a mighty way among his congregation in Northampton, Massachusetts. Two years later, when Samuel was about 13, he began to seek the way of salvation. He feared dying, and began to seek forgiveness. It is thought that Samuel was converted at the age of 12 under the preaching of Gilbert Tennant in 1736. Like the Samuel of old, God had called his name. He left the grammar school in New Jersey and returned to his parents’ farm. He went through a trying period of soul-troubling doubts and fears, but at the age of 15, he professed his faith in Jesus Christ, and united with his parents’ Welsh Tract Presbyterian Church.

The Great Awakening was now in full bloom in 1740. Although there were some excesses here and there in this movement, it was a mighty work of the Holy Spirit. Young Samuel Davies had been dedicated to the Lord by his parents, and he was destined in God’s providence to serve as a minister of the Gospel to bring the Awakening from New England into Virginia. A great revival had broken out in the home of a Virginia bricklayer who, for want of an ordained minister, began reading books and sermons to his neighbors in Hanover County Virginia. These families began sending letters to New England, asking for qualified men of God to come to Virginia and preach the Word of God to them.

Samuel Davies studied for the ministry at Blair’s Academy, and began filling vacant pulpits in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware. People everywhere were hungry for the Gospel. Samuel Davies married Sarah Kirkpatrick, the daughter of a ruling elder, in October of 1746. Upon his ordination to the Gospel ministry, the young husband was sent to Williamsburg, Virginia with a petition to preach the Gospel to Dissenters in Hanover County. This was at a time when Dissenting Ministers were not welcomed in Virginia. But the young preacher so impressed the Colonial Governor of Virginia that he was granted permission to preach to Dissenting Congregations.

The joy of a blossoming ministry was cut short by a grievous affliction. Samuel’s wife Sarah died while giving birth to a stillborn son. The loss of his wife and baby at a single blow was a terrible blow to Samuel, but he bore the affliction with the Christian’s grace. In 1748, leaving his parents and the grave of his wife and baby, Samuel boldly set his face toward Virginia. It was there that his labors would have a sweet reward. His preaching there was mightily blessed by God. At Polegreen Church, in Hanover County, he would preach to a young Patrick Henry, who later would trace his oratorical skills to the eloquent preaching of Samuel Davies.

But the ministry of Davies was effective, not merely because of his eloquence, but rather because of the Divine Grace of God poured upon a willing servant. As a true shepherd of souls, Samuel Davies visited the sick, prayed with the dying, warned the sinner, and encouraged the saints. Early in his ministry in Hanover County, he remarried. His new bride was Miss Jane Holt, who proved to be a faithful wife and devoted mother to the five children God would give them.

In 1753, Samuel Davies made a trip to England and Scotland to raise funds for the College of New Jersey, hoping to see more and more young men raised up as American ministers of the Gospel. Their work was largely successful and Davies was able to encourage his English and Scottish brethren to look in favor upon the work of the Gospel in the colonies. Davies returned to Virginia to shepherd his flock through the difficulties of the French and Indian War. His eloquent preaching encouraged men to defend their families against the attacks of the French and their Indian allies in the frontier settlements. Davies ministry in Virginia included his evangelical works among the Overhill Cherokees. He also preached faithfully to the many African slaves, and saw many of these precious souls united to his church.

In 1759, after a fruitful ministry that spanned eleven years, Samuel Davies left Virginia and returned to New England to accept an appointment to serve as President of the College of New Jersey in Princeton. He took with him his wife and children, and it was a joy to him that his Godly parents, David and Martha, were able to move to Princeton to live near him. Only 16 days after the move, his father, David Davies, went to be with the Lord, but he died in the bright hope that his son Samuel had lived an honorable and useful life of service.

Samuel Davies served faithfully as president of the College, preaching to the students, expanding the library, and encouraging young men of a new generation to live for Christ. Many of his students were important men who rose to prominence and leadership in early America. Benjamin Rush would become a medical doctor and signer of the Declaration of Independence. David Rice would be a faithful minister of the Gospel who received a call to Davies’ Polegreen Church in Hanover for a time, and then later moved on to preach the Gospel in the frontier settlements of early Kentucky.

In his New Year’s Day Sermon of 1761, Samuel Davies preached from Jeremiah 28:16, “Thus saith the Lord, This year thou shalt die.” Only a month later, on February 4, this text was remarkably fulfilled and Samuel Davies died in the prime of life at the age of 38, leaving behind a widow and young children. When his aged mother joined his family over his grave, she said, “There is the son of my prayers and my hopes . . . but there is the will of God and I am satisfied.” Samuel’s short life had been well-lived, and he left a legacy of faithfulness that continues to this day.

Drawn from Samuel Davies: Apostle to Virginia by Dewey Roberts and published by Sola Fide Publications