The book of Hebrews speaks of men of faith “who through faith subdued kingdoms, wrought righteousness, obtained promises, stopped the mouths of lions, Quenched the violence of fire, escaped the edge of the sword, out of weakness were made strong” (Hebrews 11:33-34).

These words apply very well to the life and death of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury. Unlike the typical bold and fiery Reformer, Thomas Cranmer was a man of peace, a gentle soul, a warm friend, and a man who earnestly shunned controversy. He had many days of glory, wealth, power, and prominence. Thomas Cranmer was the Primate of all England, the respected protector of kings, the trusted friend of queens, a loving husband, a devoted father, a trusted churchman, and the author of the beloved Book of Common Prayer. But the year 1556 saw Cranmer at the great crisis of his life. We will peek into the cell of his prison and see how “out of weakness, Thomas Cranmer was made strong.”

A gloomy light filtered into the dark cell of the prison where Thomas Cranmer sat. The feeble shaft of daylight illuminated a piece of paper. Cut off from the succor of his friends, separated from his wife and children, racked by grief, and bombarded by the rhetoric of his enemies, his weary heart pondered his options. Cranmer had only two. First he could assert the truth he had so long preached: that Christ alone was the head of His Church, that the mass was a Roman innovation, that purgatory was not found in the Word of God, and that man must be born again. Second, he could give in to the pressure of the age and hope to retain his position as Archbishop of Canterbury.

Only weeks before, two of his very dear friends, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, had decided for the first option. They had boldly stood for the truth, and had been burned to death at the stake. Cranmer could stand at the window of his cell and look down the street at the place where they had suffered such a cruel death. Now, if he persisted in his beliefs, their fate would be his.

His mind began to play with him. What good came of their death? Latimer and Ridley were gone. Their voices were forever silent. He could avoid their fate simply by signing that piece of paper in front of him, recanting his “errors.” But he sincerely believed the truth, and he also knew that Jesus had said, “But whosoever shall deny me before men, him will I also deny before my Father which is in heaven” (Matthew 10:33).

For many decades now, Thomas Cranmer had survived when others had died. When popular current had run against the Gospel, Cranmer, like a reed blown by the wind, had bowed over until the storm had passed. He had survived by keeping a low profile and speaking out only when it seemed that the truth would be received. He had always been a peacemaker, a gentleman, a kind-hearted soul who hated no one and sought no controversy. He was now an old man. Could he stand a burning? Would it not be easier to die in a comfortable bed like a respectable man, rather than in open shame like a criminal?

Cranmer was a gentle, timid old soul. He reckoned with himself that, if he lived, he could continue to labor for the cause of Christ. There, in the quietness of his cell, he made his decision. With trembling hand, he signed the paper in front of him. Like Peter before him, Thomas Cranmer had denied his Lord in the hour of trial.

For a while, Cranmer was relieved. He would retain his honor. A date was set in which he was to enter the church and publically renounce his errors before the assembled throng. But as the awful day of public recantation approached, Cranmer’s heart began to smite him with reproach and guilt. The words of Jesus again came throbbing into his heart. “But whosoever shall deny me before men, him will I also deny before my Father which is in heaven” (Matthew 10:33). He had done it. He had denied the Lord Jesus. He had betrayed the Christians who looked to him for leadership. He had given cause for the enemy to blaspheme.

But the deed was done. Oh, if he could only recall the ink! If only that quill pen could suck up the words. But it was too late. The recantation was submitted. The date was set for him to publicly deny the Gospel. We dare not enter the sacred ground where our old penitent sought pardon of his God. What were the agonies of his soul? How many were the tears that etched their way down those aged cheeks? What were the heart-rending cries of the man who had denied his God? But then he remembered Peter. Had not Peter also denied his Lord? Had not Peter also sought and obtained pardoned?

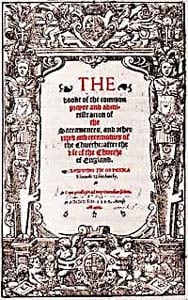

Perhaps in those sacred moments Thomas Cranmer bent his knee in his cell and turned with sorrowful eyes to the very words that he had composed in brighter days, words that had been printed in the glorious reign of Edward VI, words which now were a balm to his troubled heart,

Almighty and most merciful Father, we have erred and strayed from thy ways like lost sheep. We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts. We have offended against thy holy laws. We have left undone those things which we ought to have done, and we have done those things which we ought not to have done and there is no health in us. But thou, O Lord, have mercy upon us miserable offenders. Spare thou them, O God, who confess their faults. Restore thou them that be penitent, according to thy promises declared unto mankind, in Christ Jesus our Lord. And grant, O most merciful Father, for his sake, that we may hereafter live a godly, righteous, and sober life, to the glory of thy holy name.

The day finally came for the public recantation. With fixed resolve, the aged penitent entered the massive pulpit in the cathedral. Many people had assembled to hear the public recantation of the heretic. Some were there who had once been earnest followers of his preaching, those he had led in days past. Now, they had come to hear him deny his Lord. Their earnest faces gave the penitent new courage.

Looking upon the assembled throng, old Cranmer’s heart quailed but a moment, then his old eloquence and courage empowered his tongue. He addressed the people in carefully crafted words, proclaiming the duty of the people to live as Christians, to shun error, to be loyal to true religion. Then he got to the end of his speech. Up to this point, all the people still assumed that he would now recant his former preaching. Cranmer then said, “I come to the great thing that troubleth my conscience more than any other thing that ever I said or did in my life, and that is the setting abroad of writings contrary to the truth: which here now I renounce and refuse.”

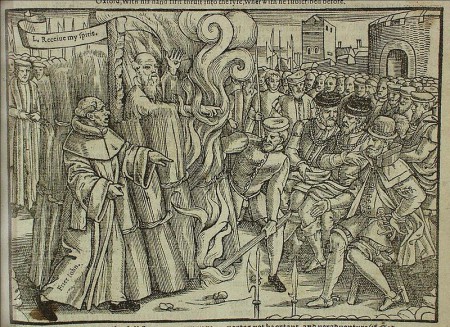

At this point, there was a moment of tense silence in the room, as concerned believers and triumphant bishops alike looked to the pulpit with fixed eyes, waiting for him to renounce his errors. Cranmer then said, “I have written many things untrue. And forasmuch as my hand offended in writing contrary to my heart, therefore my hand shall be first punished; for if I come to the fire, it shall be first burned.” The aged man still hated controversy, but his hour had come. He had bent over in the wind far too long. He squared his shoulders and continued, “And as for the Pope, I refuse him as Christ’s enemy and anti-Christ, with all his false doctrine. And as for the Sacrament . . .” Here a violent outcry of sound interrupted Cranmer, and his speech was cut short by the enraged bishops. As with the first martyr in the book of Acts, his enemies gnashed upon him with their teeth, and hauled him away to his death.

Very soon, Thomas Cranmer, once the Primate of all England, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the leader of the English Reformation, was chained to a rough stake. His wife and children were far away in the safety of Germany and would not learn of his death until the crisis was past and the battle was won.

Cranmer stood in the same place where his two friends had recently gone before him. A mixed crowd was there, a vast concourse of people, for this was none other than the highest churchman in the land of England. Some were his sincere followers from old days, the people who had earnestly followed his preaching and who rejoiced that, even in death, their teacher maintained the truth of the Gospel. Some were his mortal enemies. As the fire was kindled and the flames leaped up, true to his promise, Cranmer held his right hand directly into the fire. Cranmer did not die until the right hand was burned all the way to the stump. The old man then lifted his eyes triumphantly to heaven, his face ringed with flames but full of heavenly peace, and cried out, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.”

In his lifetime, Thomas Cranmer had indeed “subdued kingdoms, obtained promises, and wrought righteousness.” Now, in his death, he “quenched the violence of fire” and “out of weakness was made strong.”

Bibliography

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs by John Foxe

Masters of the English Reformation by Marcus Loane

The History of the Reformation by J. H. Merle D’Aubigne

The Book of Common Prayer