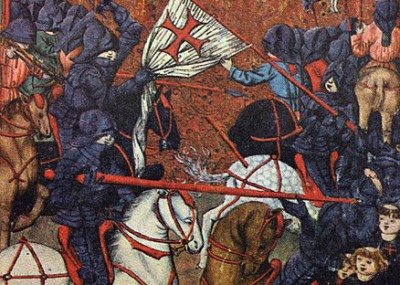

During the Middle Ages, the knights were the premiere warriors in the European continent, if not the entire world. Battles were won and lost by a relatively small number of knights in complete suits of armor. Although there were other troops on the field, often many of them, in many battles they did not play a decisive role. Yet there was one nearly forgotten group of peasants in the 15th century that defeated knights over and over again – the Hussites. These common folk of Bohemia, modern Czech Republic, were followers of the martyered John Hus, and ideological predecessors of the Protestant Reformation.

The most effective, and famous, commander of the Hussites was Jan Zizka. Today he is something of a national hero for the Czechs, and there is a massive statue of him on Vitkov Hill, the site of one of his greatest victories, overlooking the city of Prague. Zizka had a genius for organizing the Hussites, who were mostly farmers, and turning them into an effective fighting force. He developed several tactics that allowed the Hussites to defeat several crusades that were launched against them by the Catholic Holy Roman Empire.

Discipline

Zizka knew what had happened when mobs of peasants had faced knights before – complete defeat. He knew that the Hussite’s only chance for victory was through organization, so that is what he set out to do. He made sure that there were clear rules, and clear punishments for violating them. Disobedience to orders was punishable by death. Zizka also trained his armies to march fast and move quickly, so that they could move easily to strike where they were needed.

Once his army had basic training, Zizka did not immediately go out to face his most powerful enemies. He first took opportunities to try small sorties into the surrounding countryside, practicing the drills that they had learned, gaining their weapons and tactics, and experiencing the rush of battle for the first time. Gradually, through much training and practice, Zizka’s farmers were turned into a disciplined fighting force, a feat nearly unheard of at this time in history. Towards the end of his career, Zizka wrote The Statues and Military Ordinances of Zizka’s New Brotherhood, which codified the practices he had fostered in his forces, and established a code of military conduct.

Improvising

Zizka’s men lacked not only discipline, but weapons and equipment. So they improvised. They were farmers, so they turned farm tools into weapons. One of the most common were the flails, which farmers used to thresh gain. This was a long handle, with a short length of chain and then a shorter stick. These could easily be turned into fearsome weapons by embedding spikes in the shorter part of the flail.

War Wagons

Another thing that farmers would have were wagons, and this is likely where war wagons, the most famous Hussite innovation, originated. The war wagons eventually became critical to the Hussite tactics. They were wagons that were specifically designed to be turned into a fort at a moment’s notice. They were likely the first mass produced military vehicle in history. They were generally plated with iron, with wheels and panels designed to interlock when placed end to end to create a solid wall. There was a high wall on one side of the wagon, and sometimes a roof, to protect the defenders. A ramp came down to allow easy entrance and exit. There was also a container of stones handily for ballast, and to use as missiles if the enemy got too close.

As part of Zizka’s organization, the crew of the wagon was very systematized. It consisted of 20 men, each with a specific role. Two were drivers who were also armed for defense. Two were handgunners, who manned a small gun or cannon which was usually mounted on a swivel in the wagon. Six more were crossbowmen, who could fire and reload in the shelter of the wagon. Four were flailmen, whose improvised weapons worked best against enemies with anything else other than plate armor. Four were halberdiers, who carried halberds, pike-like weapons that were designed to throw fully armored knights to the ground and then finish them off with a quick blow. Two were pavisiers, who carried large shields to provide cover for those carrying flails, halberds, or crossbows, when not in cover behind a wagon.

These wagons were organized into sections of ten. An army would have a total of fifty to a hundred wagons. 50 to 100 total wagons. This provided a way to very quickly build a fort that provided a refuge that heavily knightly cavalry could not easily overcome. The “tabor,” as the wagon forts were called, could even be mobile, as long as the horses survived. Once enemy knights were worn down by attacking the tabor, they would be vulnerable when the Hussites sallied out from the wagons to counterattack.

The Hussites armies were some of the first forces of common men who were able to defeat knights through discipline and good training. They could be called the first step in the downfall of the knights. As technological changes lessened the knights’ supremacy, and other factors changed European society, crowds of pikemen and musketeers replaced the cadre of knights that had ruled the battlefield.