A French warship drifted slowly along the coast of Scotland, ominously symbolizing the bondage of the Scottish people. It was a cold icy day, and fog hung closely around the ship so that the shoreline was barely visible through the mist. A prisoner was on board, a thin man who was already past the prime of life. His body was worn down from many months as a galley slave. His health was broken. His back was sore, and he had recently been very sick. It had been many months since he had seen his native land. But as the fog began to lift, a few of his fellow-prisoners lifted their companion up so that he could peer toward the shore. They asked him what he saw. The sunken eyes of the sick man looked up through the fog, squinting to make out the skyline of the coastal town of St. Andrews, with its frowning castle and massive cathedral spires, the stronghold of Roman Papal power in Scotland. Suddenly, his eyes gleamed with life. He sat erect at his oar, trembling with hope and triumph. “Yes,” said the prisoner, “I know it well. For I see the steeple of that place where God first in public opened my mouth for His glory, and I am fully persuaded, how weak that ever I now appear, that I shall not depart this life till that my tongue shall glorify His goodly name in that same place.”

It seemed merely the vain and delirious hope of a dying man. At this time, Scotland was in the complete grip of a foreign power. A French woman named Mary of Guise was Queen Regent of Scotland, and she sat on the throne in behalf of the princess, Mary Stuart, who was being reared across the channel in the opulent court of France, drinking deeply of French customs, French religion, and French morals as well. The French fleet had been called in to enforce French power, and it seemed that Scotland would never be free from darkness, tyranny, and oppression in church and state. The powerful bishops held complete sway in the land, and simony, adultery, nepotism, and various other sins were notorious among the clergy. St. Andrews was the stronghold of their power.

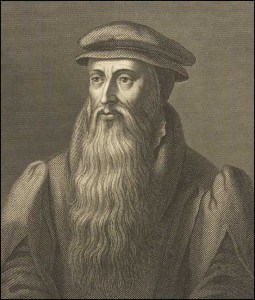

The few bold Reformers who had dared preach the truth, men like Patrick Hamilton and George Wishart, had been burned to death at the stake. On that cold and foggy day, it seemed that light and truth were gone forever from Scotland. But the light of truth burned brightly in the heart of one man. If all despaired, he would not despair. Let Queen, Regent, Pope, and council rage as they will, Jesus Christ still sat on the Throne. Although he was weak, John Knox prayed with firm resolve, “Lord, give me Scotland, ere I die.”

The God of heaven can work a mighty change in a brief period of time. Sometimes, our Lord changes a culture, a nation, a civilization slowly over the course of many centuries. But the God who brought Israel out of Egypt with a mighty hand and stretched out arm can still work a mighty revolution in a few short years. So it was in Scotland. In only ten years, Scotland would be changed forever. Far away in London, a young king named Edward VI took the throne of England. He had a burning zeal for God’s truth. By his intervention, the galley slaves were released from French vessels.

In 1549, John Knox became a free man. God was answering Knox’s prayer. All across Scotland, the hearts of noblemen, farmers, merchants, seamen, fishermen, and soldiers were being opened. English Bibles from the south found their way into homes. In 1551, Knox was invited to London to become the chaplain for Edward VI. After Edward died, Mary Tudor took the throne and Knox was forced to flee to the continent. Again, it seemed his hopes were vain and empty. In 1553, John Knox became pastor of an English-speaking church in Geneva. Away from loved ones, hopes, plans, and ambitions, Knox prayed on: “Lord, give me Scotland, ere I die.” In 1555, Knox secretly returned to Scotland. He sought to urge the nobles of Scotland to do their duty, and throw off the yoke of idolatry. He preached and taught wherever he had a hearing, right under the noses of his enemies. While in Scotland, John Knox married Marjory Bowes and took his young wife to the safety of Geneva.

In 1558, from Geneva, Knox wrote a series of three blazing letters. The first he titled “First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women.” In this treatise, he proclaimed that the rule of female monarchs was a judgment upon Scotland for her idolatry. At the same time, Knox also wrote his “Appellation to the Scottish Nobility,” in which he pleaded with the noblemen to abhor idolatry, renounce the authority of the Pope, bow to the supremacy of the Law of God, and purge the land of oppression in church and in state. The third letter was a “Letter to the Commonalty of Scotland,” urging upon fishermen, shepherds, and farmers their duty before God.

These three treatises had a remarkable effect upon the realm of Scotland. Psalm 110:3 declares, “Thy people shall be willing in the day of Thy power.” The Lord always makes his people willing to act when the day of His power comes. Soon after these letters were sent, several noblemen, soon to be called “the Lords of the Congregation,” wrote to Knox, asking him to return to Scotland and lead them in the work of Reform.

In 1559, John Knox returned in triumph to his native land. Only ten years before, he had been a galley slave on a French ship, peering through the fog at the Cathedral of St. Andrews. Now, he was back. It was a dramatic showdown of power. St. Andrews was the stronghold of Papal power in Scotland. The Queen Regent hated Knox for his “Blast of the Trumpet” and for his defiance of her tyranny and idolatry. Knox had been publicly burned in effigy, and he knew the enemy sought his life. Knowing of Knox’s intention to come to St. Andrews, the Bishop sent a message to the Lords of the Congregation, threatening to have 100 spearmen outside the church to prevent Knox from entering that pulpit.

Knox was not a man to quail before such threats. He said, “My life is in the hands of Him whose glory I seek, and therefore I fear not their threats.” The Lords of the Congregation backed Knox with their own men-at-arms, and Knox entered the pulpit of St. Andrews and boldly preached against the Queen and the Bishop, asserting that Jesus Christ is supreme in church and state. To the astonishment of all, the civil magistrates of St. Andrews agreed to rid the town of all monuments of idolatry. Altars of mass were overthrown, images were toppled, carvings were chiseled out of niches, artwork was removed from walls, candles were snuffed out, and the pulpit became the simple and central focus of public worship. Immediately, the Queen Regent launched her troops against the Reformers. The Lords of the Congregation would not back down, but banded together to defend with the sword of civil power the Gospel that Knox preached.

In 1560, the Queen Regent died, and the young Mary Queen of Scots came to rule the realm in her own right. John Knox became pastor of the Church of St. Giles in Edinborough where he preached the truth right down the street from the palace of the new Queen. Mary Queen of Scots was young, beautiful, and persuasive, but Knox could not be moved by tears, smiles, threats, or false promises. During one interview, Mary Queen of Scots said that her conscience was assured that the Roman religion was correct. Knox replied respectfully but boldly, “Conscience, Madam, requireth knowledge; and I fear that right knowledge ye have none.” He also told her, “If princes exceed their bounds, Madam, no doubt they may be resisted, even by power.”

On another occasion, when Mary wept bitterly over Knox’s rebuke of her immorality, he answered “I never delighted in the weeping of any of God’s creatures, but seeing I have spoken the truth as my vocation craves of me, I must sustain your Majesty’s tears rather than betray my Commonwealth through my silence.” Eventually, the young queen’s bad morals and secret plots became so outrageous that Mary was deposed and convicted of treason, adultery, and idolatry.

By the time of Knox’s death in 1572, Scotland was thoroughly Reformed. The pulpits were aflame with truth. The Lords of the Congregation were triumphant. Idolatry was outlawed throughout the land. The Scottish nobility had boldly united in covenant to uphold the Law of God throughout the realm. When Knox was dying, he asked his wife to read from John 17, the passage instrumental in his conversion many years earlier, saying, “there I cast my first anchor.” One of the Scottish earls said of Knox, “There lies one who in his life never feared the face of man.”

In our current crisis, we need the confident hope of Knox. America cannot be made great by a political party or a conservative candidate. A nation will only prosper when it will unite in covenant to acknowledge Christ as King and His Word as Law.

Bibliography

The Reformation in Scotland by John Knox

John Knox: A Biography by Peter Brown

Knox and the Reformation Times in Scotland by Jean L. Watson

The Scots Worthies by John Howie