Editor’s Note: This post on Tales of Mighty Men comes to us from Stephen Huffman

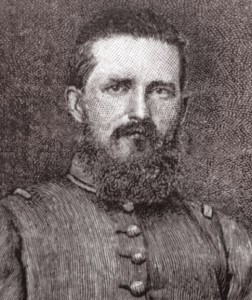

In many ways, Elisha F. Paxton exemplified the Confederacy whose uniform he wore. He had a typical Southern background. His family was Scots-Irish, and had fought the Stuart monarchs in the 17th century. After immigrating to the American colonies, his ancestors had settled on the Virginia frontier and espoused the Patriot cause in the War for Independence. His domestic life was typical of the Southern gentleman farmer. Although he had aspired to military service, poor eyesight prevented him from attending West Point. Instead, he studied law, but when he became completely blind in one eye, he took up farming.

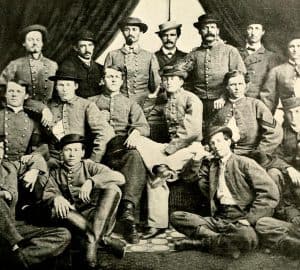

Paxton had strongly Southern political views. Devoted to constitutional liberty, he advocated secession long before most Virginia moderates were willing to take that step. After the war began, he had a successful military career. He was noted for gallantry at First Manassas and had gained the trust of Stonewall Jackson, who appointed him his Chief of Staff. Later, Jackson promoted him directly from the rank of Major to Brigadier General (bypassing all the colonels) and placed him in command of the Stonewall Brigade.

At home and on the battlefield, Paxton exemplified Southern chivalry. Although he was a fierce fighter on the battlefield, he was very tender to his three small children and to his wife, to whom he wrote every week. Moreover, he had a great respect for Christianity. When at home in Lexington, Virginia, he attended the same Presbyterian church that Jackson attended, and he was very courteous to the chaplains in his brigade. But at the time he took command of the Stonewall Brigade, he had made no profession of faith, although admiring “religion” in others.

Perhaps it was in this that he most resembled the Confederacy. Throughout the formation of the Confederacy, Southern politicians made frequent appeals to God, and many were the assertions that the new Confederacy was to be a Christian republic. But the Confederacy failed to recognize the full ramifications of what it means to be “Christian.”

In 1861, when the Confederate Constitution was being drafted, James H. Thornwell proposed the following provision: “We, the people of these Confederate States, distinctly acknowledge our responsibility to God and the supremacy of Jesus Christ as King of Kings and Lord of Lords; and hereby ordain that no law shall be passed by the Congress of these Confederate States inconsistent with the will of God, as revealed in the Holy Scriptures.” Tragically, the churches of the South refused to support Thornwell’s proposal, and it never made it into the Constitution.

Thus, in spite of its many virtues, the Confederacy was destined for ultimate failure—not because it was wrong to resist federal tyranny, or because of inept military leadership in the west, or the lack of foreign recognition, or the industrial might of the North. Rather, the South’s defeat was due to its refusal to seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness.

Throughout the struggle, the South’s great theme was defending the liberty granted to them by their fathers. God had given liberty to the American people as a reward for the early intention of men such as William Bradford and John Winthrop to establish a godly society based solely on the law of God. Because they made God’s law their first priority, God granted them liberty from the tyranny of the Stuart monarchs, economic prosperity, relative security from the persecutions and wars of Europe. These blessings were not their aim, but because they sought first the kingdom of God, these things were added to them.

But the South ignored the requirement in pursuit of the reward. Instead of adopting Thornwell’s proposed preamble, the Confederacy adopted a preamble similar to that of the United States, listing as their purposes “justice,” “common defense,” “domestic tranquility,” and the “blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” The Confederate preamble did invoke “the favor and blessing of Almighty God,” but without any mention of the law of God, this was mere lip-service. “Southern rights” took priority over Christ’s kingly right to have his law enforced by his ministers in civil office. In a lecture on Stonewall Jackson, Robert L. Dabney commented:

How righteousness exalteth a people! Shall this judgment and righteousness be the stability of thy times, O Confederate, and strength of thy salvation? And these mighty deliverances, . . . were they not manifest overtures to us to have the God of Jackson and Lee for our God, and be saved? “Here is the path; walk ye in it.” And what said our people? Many honestly answered, “Yea, Lord, we will;” of whom the larger part walked whither Jackson did, and now lie with him in glory. But another part answered, “Nay,” and they live, on such terms as we see, even such as they elected. . . . But they would not be free on such terms. Nay; they preferred rather to walk after their own vanities. Verily they have their reward!

Until late 1862, Paxton, like most Southerners, was content to fight for freedom on his own terms. But shortly thereafter, he became a recipient of God’s saving grace. His conversion was not dramatic, but genuine, and it was soon evident that the commander of the famous Stonewall Brigade was thoroughly changed. Some have traced much of the fruit of the subsequent revivals in the Army of Northern Virginia to the example of General Paxton’s conversion.

But for Paxton, conversion did not only mean a home in heaven. It meant a change in everything he did, including the way he fought battles—and why. An extended quotation from his last letter home sums up his new views of life and of the Confederate cause.

Our destiny is in the hands of God, infinite in his justice, goodness, and mercy; and I feel that in such time as he may appoint he will give us the blessings of independence and peace. We are a wicked people, and the chastisement which we have suffered has not humbled and improved us as it ought. We have a just cause, but we do not deserve success if those who are here spend this time in blasphemy and wickedness, and those who are at home devote their energies to avarice and ambition. Fasting and prayer by such people is blasphemy, and, if answered at all, will be by an infliction of God’s wrath, not a dispensation of his mercy.

Whenever God wills it that [my life] pass from me, I feel that I can say, ‘Into thy hands I commend my spirit.’ In this feeling I am prepared to go forward in the discharge of my duty, striving to make every act and thought of my life conform to his law, and trusting with implicit faith in the salvation promised through Christ. How I wish that . . . every thought, act, and feeling of tomorrow would have its motive in love for God and its object in his glory!

On the morning of May 3, 1863, Paxton led his brigade into action at Chancellorsville. He was not involved in Jackson’s night attack on the Union right flank. Rather, he had been detailed to guard the Orange Plank Road. But during the night, his fresh brigade was summoned to spearhead the morning assault on the reinforced Union position at Fairview. When the order to attack came, Paxton put his Bible in his pocket and led forward his brigade. Moments later, he fell, pierced through the heart by a Yankee minié-ball.

Jackson, who himself lay mortally wounded, wept when he heard of Paxton’s fall, for perhaps, more than any other man, Paxton shared Jackson’s whole-hearted devotion to Christ’s kingdom.

As Dabney said, those who sought first God’s kingdom and righteousness died as heroes. The South at large was condemned to reap the fruits of disobedience. The difference between Paxton and his Confederacy was in “striving to make every act and thought” conform to God’s law.