| Libby Prison |

Although most of the prisoners avoided “Rat Hell,” three of the Union officers saw it as an opportunity to escape. They found a way to secretly access it by climbing down a chimney in the wall. This alone took fifteen days to accomplish, as they only had pocketknives to remove the bricks. With their plans in place, the prisoners started digging. But before long they hit a snag. They found that the building was built on large timbers. After a tremendous amount of work they were able to saw through those with their pocketknives, but then the tunnel began to fill with water and it had to be abandoned. They tried at another spot to hit a sewer through which they could climb to safety. But when they caused a furnace to collapse they halted that attempt to avoid being detected. It was then decided to go out through the sewer that led out of the kitchen, but days of work were necessary to widen that passage so men could fit through. All was believed to be ready for an escape on the night of January 26th, but the last bit of work took longer than expected, and the tunnel began to fill with water.

|

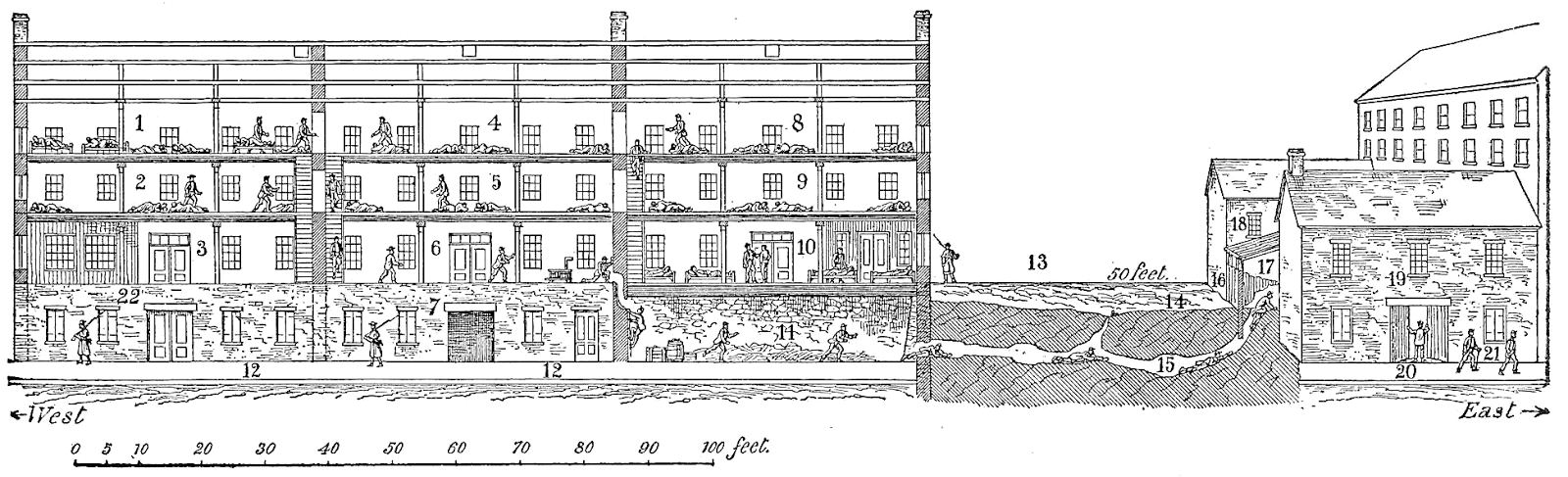

| Map of the prison and tunnel |

With this third failure, another group took over the project and began work on a new tunnel starting from the cellar. The first day of work, when they had to break through the brick wall with an old ax, happened to be the same day the Confederates were installing grates on the windows. This, combined with plenty of stomping by the other prisoners, covered the sound of the work. They then began working on digging the tunnel with a pen knife. The work was done in shifts. Two men went down at night and dug, hiding there during the day until they were relieved the next night. The dirt was packed and hid under a pile of straw in the cellar. The longer the tunnel grew, the more workers were needed, until there were fourteen men handing the dirt out to the opening, using a spittoon with a rope attached. The working conditions were very bad. As one of the diggers wrote:

[I]t was impossible to breathe the air of the tunnel for many minutes together; the miner, however, would dig as long as his strength would allow, or till his candle was extinguished by the foul air; he would then make his way out, and another would take his place – a place narrow, dark and damp, and more like a grave than any place can be short of a man’s last home.

The work would have never been done in normal circumstances, but they were driven on by the hope of escaping from Libby Prison. Another prisoner wrote, “No tongue can tell…how the poor fellow[s] passed among the squealing rats,—enduring the sickening air, the deathly chill, the horrible interminable darkness.”

They work had to stop after several prisoners were able to slip pass the guards. Security was heightened, and the guards began to do roll call. At one rollcall when the prisoners were collected, two were missing, as they were down in the cellar. They were able to talk their way out by saying they had just been missed by the officers doing rollcall. But another time one officer was again in the tunnel during rollcall. The guards decided that he escaped, and the prisoners decided he would have to remain in hiding in the cellar to avoid giving away the plan.

|

| Diagram of the tunnel |

After 17 days of digging, it was decided that the tunnel was long enough to reach a tobacco shed, about 50 feet away. But when they broke into the air that night, it was found that they had missed the shed and were within sight of the sentries. Thankfully they did not see the hole before it was closed up. The tunnel was extended to its final length of 57 feet, right beneath the shed. The escape was made on February 9th, 150 years ago today.

The escape was very successful. 109 prisoners made their way out of the tunnel and walked out of the prison gates without attracting the attention of the sentries. The guards believed that escape was nearly impossible, so they were not particularly careful in keeping watch. When morning came the tunnel was closed and the remaining prisoners tried to hide the large number of missing men. Inevitably the escape was discovered, and pursuit was made. Many of the officers had fought in the area before being captured, so they were familiar with the terrain. 59 of the escapees were able to reach the Union lines, 48 were caught by the Confederates, and two drowned in the James River.

More of this fascinating story can be found in Four Months in Libby, and the Campaign Against Atlanta by Captain L. N. Johnston.

This post originally appeared on the Civil War 150th Blog.