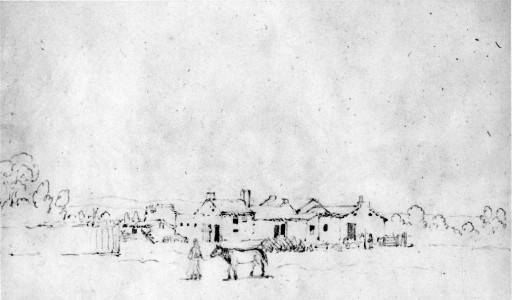

A solitary medical doctor urged his horse forward into the cold and foggy November night. Behind him lay the safety, warmth, and comfort of a fort. Ahead lay danger, mystery, and a long ride back to his isolated Presbyterian mission station called “Waiilatpu” – the place of rye grass. In the wee hours of the morning, Marcus Whitman rode into the mission compound at Waiilatpu. Ten years earlier, this had been a wilderness, inhabited only by wild beasts and wild men. Now there were cultivated fields, orchards, flocks of sheep, herds of cattle, and a gristmill. This clearing had come to represent a clash between two cultures. On one side of the clearing were the lodges of the Cayuse, where even now could be heard the muffled death wail of a bereaved Indian family. On the other side of the clearing were five covered wagons, a vivid picture of Westward expansion.

In the middle of these two cultures stood Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. Ten years ago, they had left their homes in rural New York to come into this wilderness with the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Some Cayuse had welcomed their influence, had abandoned their pagan ways, and had come to embrace Christianity. They had ceased their witchcraft, their murder, and the horrid practice of burying alive their unwanted children. These Cayuse had learned to cultivate the ground, to raise cattle, and to love their children. But some Cayuse had not appreciated the Whitmans’ sacrifice. Fear, resentment, and suspicion ran deep. In the last few weeks, muttered threats and secret pow-wows had broken out into open resentment. Indians were dying of a measles epidemic despite the best efforts of Marcus. It was a Cayuse custom to kill a “tewat” – medicine man, if his patient died. Marcus knew that the Indians also resented the growing influx of white men from the east. But Marcus could not change history. He could only do what he could to help the Indians adapt to a changing world.

Marcus dismounted at the T-shaped mission house. It was late, and Marcus was tired. But he sent his wife, Narcissa, to bed so that she could get some needed rest, her last on earth. Marcus took her place attending the sick children, white and red alike, who needed his aid through the rest of the night.

Perhaps a great flood of memories swept over Marcus that night. He recalled the day when he, as a young medical doctor sitting in a church in rural New York, first heard the missionary Samuel Parker tell of the tribes beyond the distant Rockies. He remembered the day that Narcissa Prentiss had agreed to become his wife. He remembered how, at their wedding, Narcissa had requested that the congregation sing the great missionary hymn, “Can I Leave You?” He remembered that, by the fifth verse, the song was stifled by sobs as his courageous bride sang alone this stanza:

In the deserts let me labor,

On the mountains let me tell,

How he died—the blessed Saviour

To redeem a world from hell!

Let me hasten, let me hasten,

Far in heathen lands to dwell.

They had already given so much. Narcissa, so young and eager, was already broken in health. Marcus too was worn with care and toil. And not far away, Alice Clarissa, their only child, rested in a shallow grave—drowned in the Walla Walla river at the tender age of two. The Whitmans had sacrificed wealth, home, family, friends, society, and their own health to come and labor here. But they still had one thing more they could give. The supreme test of their loyalty would come with the dawn of a new day.

On November 29, 1847, a band of hostile Cayuse came to the main mission house, demanding medicine. Marcus had dealt with angry men before, and he hoped for the best. He could not deny their request and reached for his bag. One of the Cayuse warriors stepped behind Doctor Whitman, drew a concealed tomahawk from his belt, and slammed the blade into the base of the doctor’s skull. A shot was fired, and instantly all was confusion. Narcissa must have known what the gunshot meant. But she did not panic. Her first thought was not for herself, but for the little orphan girls of the Sager family who depended upon her. Bolting the door to her room, she gathered the children about her as a general massacre began outside. The fury of the murderers would not be restrained even by the sight of women and children. A gun was thrust into the window, and a bullet tore through Narcissa’s shoulder, wounding her severely.

Several of the immigrants from the east were slain in the yard. A ministerial student named Andrew Rogers, a descendant of Scottish Covenanters, could have escaped, but instead he ran toward the compound to defend the women and children and was mortally wounded in the process. With his life’s blood ebbing away, Andrew Rogers fought on. Getting Narcissa and the orphan girls upstairs into a loft, he kept the murderers at bay for over an hour with the broken end of a gun barrel. At last, the wounded Narcissa was lured out of the house by promises of safety. On the way out, she passed her husband lying in a pool of blood. Amazingly, he was yet alive. Their conversation was brief, but he assured her of his love for her and his confidence in God’s eternal purposes. As Narcissa came trustingly outside, a volley rang out and she was instantly pierced by several balls. She had given her all for the Cayuse. She had nursed the Indian children, taught them to read the Bible, taught them to pray, and to sing the name of Jesus. She had been faithful unto death, and now was to receive the crown of life.

The massacre did not end with the killing of the Whitmans. All the able-bodied men the Indians were able to find were massacred. Helpless women and children were savagely abused and held ransom for almost a month. Finally, the women and children were saved after a thrilling rescue. After a search that took several years, justice was eventually served upon all of the murderers. Some of the murderers were tracked into the Blue Mountains by a Christian Nez Perce chief, and some of the guilty Cayuse were slain in battle. Five of the murderers, including the two men who personally slew Marcus and Narcissa, were brought to trial and convicted of capital murder by a jury that included converted Indians.

What became of the martyrdom of Doctor and Mrs. Whitman? Was their sacrifice in vain? Did a young doctor and his bride waste their potential when they went “far in heathen lands to dwell”?

The obscure mission station called Waiilatpu was obscure no more. Newspapers in the east were soon ablaze with the stirring account. In those days of slow mail, the newspaper was the way that relatives in New York first learned of the martyrdom. Judge Prentiss, as he read the headlines handed him by his grieving wife, must have remembered the image of his daughter, an eager young bride, singing:

In the deserts let me labor,

On the mountains let me tell,

How he died—the blessed Saviour

To redeem a world from hell!

A great wave of interest in missions swept across the United States in the coming years. Boys and girls, inspired by the courage of the Whitmans, took up the banner of Christ. Henry Spalding, a steadfast friend of the Whitmans who labored at Lapwai, a mission station east of Waiilatpu, returned to the field after the tragedy, reaping a great harvest that had been sown among the Cayuse and Nez Perce. A converted chief named Timothy became an earnest and dedicated Christian. Spalding’s church in Idaho still exists to this day as a testimony to the martyred missionaries.

In the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. stands a statue of Marcus Whitman, clad in buckskins. He holds a Bible in one hand, and saddlebags full of medical supplies in the other. His life and influence have not been in vain for Marcus and Narcissa served a God who has promised, “My word shall not return unto me void, but it shall accomplish that which I please, and it shall prosper in the thing whereto I sent it.” (Isaiah 55:11)

Drawn from Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and the Opening of Old Oregon by Clifford Drury