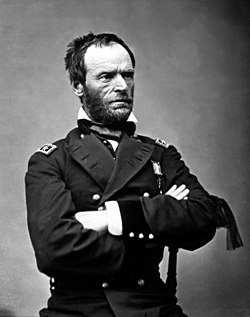

This month is the 150th anniversary of Sherman’s infamous March across Georgia to the Sea. After years of war, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman had the opportunity to strike through the heart of Confederacy. His goal was to undermine the Confederate war effort by breaking the civilians’ will to fight. As he wrote after the march to Henry Halleck, the Union’s Chief of Staff:

We are not only fighting armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies. I know that this recent movement of mine through Georgia has had a wonderful effect in this respect. Thousands who had been deceived by their lying papers into the belief that we were being whipped all the time, realized the truth, and have no appetite for a repetition of the same experience.1

Today many, especially in the south, remember Sherman as a cruel man who burnt the homes and crops of Georgians, forcing them into poverty and starvation. Debates continue to rage today whether he should be considered a war criminal, or simply as a general who knew now to end the war. In this article, we will consider the legend that has grown up around Sherman’s march, and how we can separate the myth from fact.

How Bad Was it?

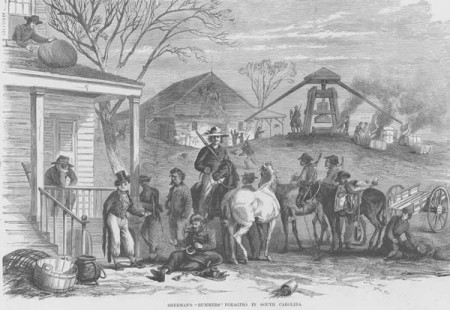

First, what did the Union troops actually do? How bad was it? Before the march began, Sherman issued Special Orders No. 120. In it he gave strict instructions for how his men were to conduct themselves on the march. They were allowed to “forage liberally” from the countryside, and were given nearly free reign to take or destroy food, horses and livestock. However, they were not to enter homes or burn any buildings without express orders from the corps commanders.2 These orders were often violated with impunity, and the Federal generals did little, if anything, to stop it. The problems began even before the army even left Atlanta. Sherman had ordered that military targets, such as the railroad depot, be destroyed. But the men disregarded regarded these orders, and about half the town was burnt. “Can’t save it,” Sherman commented to a staff officer, “Set as many guards as you please, [the men] will slip it and set fire.”3

The Federal troops, Bummers as they were called, routinely violated orders along the march and burnt many houses along the way. However, they did not destroy everything in their path in a scorched earth policy as many believe today. In the 1930s a survey found that many, if not most, houses were left standing in the wake of the Yankee march.4

This does not mean there was no suffering for the civilians involved. Sherman and his men were determined to make the southern people feel the cost of the war, to “make Georgia howl,” and they were successful. One woman’s experience was typical:

Happening to turn and look behind, as we stood there, I saw some blue-coats coming down the hill. … I hastened back to my frightened servants and told them that they had better hide, and then went back to the gate to claim protection and a guard. But like demons they rush in! My yards are full. …

To my smoke-house, my dairy, pantry, kitchen, and cellar, like famished wolves they come, breaking locks and whatever is in their way. The thousand pounds of meat in my smoke-house is gone in a twinkling, my flour, my meat, my lard, butter, eggs, pickles of various kinds – both in vinegar and brine – wine, jars, and jugs are all gone. My eighteen fat turkeys, my hens, chickens, and fowls, my young pigs, are shot down in my yard and hunted as if they were rebels themselves. Utterly powerless I ran out and appealed to the guard.

‘I cannot help you, Madam; it is orders.’ …

As night drew its sable curtains around us, the heavens from every point were lit up with flames from burning buildings. … My Heavenly Father alone saved me from the destructive fire.5

Was it Unusual?

How unusual was the March through Georgia, versus any other Civil War era army marching past? No Civil War era civilian would have wanted an army to march through his property, even if he sympathized with their side. He could still expect to have animals go missing and his fences be turned down and used for firewood. Some commanders, such as Robert E. Lee, tried to stop this. When invading Pennsylvania he reminded his troops they made, “war only upon armed men,” and exhorted them to “abstain with most scrupulous care from unnecessary or wanton injury to private property.”6 Other armies used harsher tactics were also used. Chambersburg, Pennsylvania was burned by Confederates after the townspeople failed to pay a $500,000 ransom.

What distinguished Sherman from most other armies was the intentionality of his destruction. His actual orders were not far from the ordinary, but in his correspondence made his intentions clear. Although other armies wrought similar kinds of destruction, Sherman was different. He launched a campaign for the sole purpose of making war on civilians and turning them against the war. Where other generals tried to constrained the depredations of their men, Sherman encouraged them.

Was He a War Criminal?

Some today argue that Sherman was a war criminal. He was, of course, never prosecuted for his crimes – victors rarely are. In 1863 Lincoln had signed what is called the Lieber Code – the laws of war for the United States armies in the field. This order required that private property be respected, and if military necessity required it to be seized, that the owners be given receipts so they could be indemnified.7 Sherman may have technically been in a gray area. But he said he intended to bring “the sad realities of war home to those who have been … instrumental in involving us in its attendant calamities.”8 He clearly was in violation of the spirit of the Lieber Code, the intention of which was to preserve private property whenever possible, not destroy it. If Sherman did the same thing today he could be considered a war criminal. The 1977 Geneva Conventions, which the United States has not ratified, prohibits targeting civilian food, livestock or water.9

What about Other Wars?

It would be easy to condemn Sherman’s actions against the southern people, but it is important to remember how they fit into the future actions of the US Military. The March to the Sea is considered to be one of the first instances of modern warfare, where a scorched earth policy is used and the enemy civilians are a valid and legal military target. Sherman’s actions were child’s play compared to the United State’s policy during World War II, where the enemy countryside was freely bombed. The attacks on Germany and Japan were not, like Sherman’s, on only the supplies and infrastructure of the country. The attacks, culminating in the atomic bombings were intended to kill as many noncombatants as possible. It is ridiculous to even think of comparing Sherman’s march, where the civilians had a few years of hardship while recovering from the destruction, to the bombing of Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima or Nagasaki, where hundreds of thousands of men, women and children were killed. Rejecting what Sherman did requires the rethinking most of the United State’s wars in the 20th century.

1. Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, series I, vol. XLIV, part 1, p. 798.

2. Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, by William T. Sherman (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1875), p. 174-176.

3. Marching with Sherman by Henry Hitchcock (University of Nebraska Press, 1995) p. 53.

4. Rethinking Sherman’s March by W. Todd Groce, (New York Times)

5. A Woman’s Wartime Journal by Dolly Sumner Lunt (New York: The Century Co., 1918) p. 21-23, 30-31.

6. Official Records, vol. XXVII, part 3, p. 943.

7. Instruction for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field by Francis Lieber section, 2, paragraph 38.

8. Official Records, vol. XLIV, p. 13.

9. Geneva Conventions, Protocol I, Article 54.

As an ancestor of a Yankee soldier, I agree that Sherman was a war criminal. We can try to rationalize his behavior and actions, but in the end we can only judge what happened. He did not follow the law of the time and he sought out to hurt women and children. You cannot compare actions of WWII with his actions as you are comparing apples to oranges. Different time, different means, an existing law, and not American against American. Shame on Lincoln for supporting him.

Lisa, You are a descendant, not an ancestor. You have a right to your opinion, but while he certainly was no more perfect than any other human, he was right in one essential thing. The only way to stop a war is to make those both fighting and supporting it want to do that. He would have done better by history if he had made efforts to recruit Atlanta’s business community to take charge of the city, prevented actions such as Ebenezer creek and if Pres Andrew Johnson had not nullified his 40 acres and a mule field order. But could he personally constrain an Army that had endured the depredations of three years of hell ? I think not, even if he had wanted to (which is debatable), it was a battle no General could have won. As told in this piece, most of the homes along the route of march, from Atlanta to Savannah, were not burnt or destroyed. The prisoners of war, both at Andersonville (which I recommend be visited) and the northern prison camps bore the worst of the suffering. In the case of most southerners, as a result of supporting the minority (white plantation owners) and fighting their war for them, while many were exempted from service based on the numbers of slaves owned. This war was not about slavery, some say, I say read the record and judge them for their acts, both during the war and for the next 100+ years.

The stories of how Sherman’s soldiers raped women is not even mentioned in this article.

“A few years of hardship” is not what a woman lives with after her home has been burned, her food stolen and her very soul has been torn from her through rape.

Not starting the war in the first place would have ended it much sooner, i.e. before it began. Fighting for the aggressor* affords Sherman no room to complain about how long the conflict had lasted or how brutal it had been.

This isn’t even up for debate. 3 States (Virginia, New York, and Rhode Island) only ratified the Constitution explicitly on the condition that they could secede, secession was not among the constitution’s restrictions on the states, the constitution grants the federal government no power to stop secession, and the power to dissolve their membership is naturally among those reserved to the states by the tenth amendment. Whatever their reason for exercising their right is completely immaterial. They could have seceded because they didn’t like the new drapes in the capitol building and the federal government would have been equally unauthorized to do anything.

Well put Jacob. I am generally blown away by the intellectual gymnastics which are deployed by those who argue against the constitutionality of secession. What Lincoln was doing was a redefining of the relationship between the federal government and the states, and he was doing so with the barrel of a gun.

Slavery was a deplorable institution and had to go, but the war actually had much less to do with the specifics of slavery than most people think. The war absolutely was a war of northern aggression in so far that Lincoln and his cadre were spoiling for it and eventually got what they were after.

My Dad explained Lincoln’s objective by focusing on the word “UNITED”. Prior to the Civil War we were the united States of America with the word UNITED being an adjective. It describes the relationship of the States with each other. Similar to the word Southern when applied to the States in that region. After the Civil War we changed to the United States of America with the word United now taking the role of a Noun describing the joint states with a proper name.

My Dad is long since dead, and I miss those talks, but this shift from lower case u to upper case U pretty well sums up what happened. It was not like the Constitution changed, just a redefinition of what the terms meant.

TFilsom, sophistry aside, your reply to Lisa is essentially a justification for Sherman’s actions, which were criminal in their day and certainly so by today’s international legal corpus which governs how armies and their commanders should conduct themselves. To be fair, you are merely elaborating upon the sophistry which forms the basis for Mr Horns argument found throughout this article.

If the question really is “Was Sherman a war criminal?”, then the answer is clearly in the affirmative. Period. Full stop. But both you and Mr. Horn seem more interested in providing justifications for Sherman’s actions.

Yes, Sherman was and remains a war criminal. And more Americans would follow in his footsteps. Heck, it is too bad that there was no CIA in the 1870s, perhaps Sherman would have made a great director, much like that much more recent immoral criminal, Gina Haspel.

Hi Raymond,

I think you may have missed the point of the article. While I did try to lay the facts out in such a way that someone can come to their own conclusion, I actually agree with you. I think Sherman’s actions were immoral and were war crimes, as were far too many actions perpetrated by representatives of the US government, military and civilian, throughout our history.

God Bless you Lisa!

This coward then turned this “tactic” upon the Lakota Tribes. Using his Total War to reduce the Buffalo Herds from 60 million to just under 2 thousand to commit genocide on the Plains Indians.

He should be dug up, stripped of all rank and honors, and buried in a unmarked grave not with real military men.

Sherman is not buried in a military cemetery, so you don’t need to worry about that. But if we are going to start digging up every general who ordered and allowed immoral activities in our country’s wars, what about the soldiers who participated in them? How many graves would be left?

That’s not an accurate analysis in any way. Sherman freed tens of thousands of slaves, from hellish lives of forced labor, rape, and sale far away from their families. Perhaps more than any other General, he is respoinsble for saving as many as perhaps 75,000 people. And, you copletely ignore the fact that the orders for the march were to bring destruction to plantations which had enslaved those people, so I have no sympathy whatsovever for them. Finally the CSA army tried to stop him through what I would describe as scrimishes, but they lost because Johnston’s army had been drastically reduced by desertion, to a level of many 20% left. The deserted because they realized that preserve slavery was not worth their lives, and because the war was nearly over. Read Mary Chestnut’s Civil War diariers. She was based in Charleston, and was incredibly grate ful that Sherman did not burn the town or kill the plantation owners who felt free to enslave thousands.

Finally 3100 casculaties were incurrred in total, 2100 of those were USA soldiers. Very few civilians died – so we’re only talking about property damage. If destruction of property were a war crime (now or then) , the CSA army should have been charged for burning down Chambersburg in 1864, where no USA army was anywhere near to defend them, just because they could not raise the money the CSA army demanded. During the Gettysburg campaign, Confederate troops restrained themselves from destroying non-government property. By the Rebels’ next raid into the North, however, the policy had changed.

On July 30, 1864, Brigadier General John McCausland and 2,800 Confederate cavalrymen entered Chambersburg and demanded $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in greenbacks. The residents of Chambersburg failed to raise the ransom, and McCausland ordered his men to burn the town. Flames destroyed more than 500 structures leaving more than 2,000 homeless. One resident died of smoke inhalation. Damage was estimated at more than $1.6 million. To make matters worse, many inebriated Confederate soldiers looted homes and abused civilians. Mobs of angry townspeople looking for retribution killed several Rebels.

Good Samaritans in the Rebel ranks helped citizens escape and save their valuables; a Confederate captain even ordered his company to douse the flames. One officer, Colonel William Peters, staunchly refused to take part in the burning. McCausland had him placed under arrest.

Chambersburg was the only Northern town the Confederates destroyed. The attack inspired a national aid campaign and spurred the Union Army to the aggressive approach that finally won the war.

So, Sherman may not have been a saint, but he was certainly no war criminal. He learned a lesson from the CSA, that bringing war to innocent civilians could bring the Civil War to an earlier end. In that way, he saved untold lives.

The Confederate staes made a serious mistake in seceding. They made a worse mistake in starting the war. If there is ultimate blame to be assessed, it is the plantation owners/politicians like Jefferson Davis and Alexander Stephens who should have been tried for treason.

But, after sudden and total slave release, what happened to those slaves? Many had nowhere to go and nothing to do. At least before the war they had work, food and shelter. Your jutifucation of Sherman is very “ends justify the means” which is a pretty poor argument to keep Sherman up on.

Yours, Caleb.

If the south “made a mistake” in seceding, what about the North and their tariffs that punished the south before the war ? Did not you hero “Ape Linchrome” order 75,000 Federals to INVADE the south. Lastly as per another poster, seceding was actually CONSTITUTIONAL or allow by it. You need to read more or post less

if you think he was a war criminal you’re no yank

Yup, I ain’t a Yank.

Thank you for your moral compass, which can be unconditionally supported by the word of God which came to a prophet Shemaiah, who single-handedly told Solomon’s heir that he dare not go up to fight against his brothers, the sons of Israel in the northern kingdom. One man stood and said, Go home, Rehoboam, you and your army. “So the Judahites obeyed the word of Yahweh and went home again, as Yahweh had ordered” (1 Ki 12:24). This incident does not say much for American religious culture, backed by pompous fools and clerics who found a way to justify Lincoln’s barbarous means to justify their ideals, untempered by wisdom. I would not want to stand in their shoes on judgment day. I am from PA; my ancestors refused to join Lincoln’s forces, along with the rest of the Anabaptists and Amish, and were blessed for their civil disobedience.

Right. And then there is the tragedy of the Roswell Mill workers, who were sent North by him — women, some pregnant, with their little children. They were taken against their will to Louisville, KY, or across the Ohio River to Indiana, where they were released to fend for themselves with no food, no shelter, and defenseless. Such brutality is a stain on the reputation of the United States. Sherman is a war criminal.

Sherman was a hero. He brought the war to the rebs, and showed them the cost.

Amen brother

Why don’t the Yankees quit retiring south to make us pay the same as their union cities they turned into an expensive poop hole they couldn’t wait to leave. You love the north, stay and keep your communist democrat ideas.

Americans can move wherever in the country they want to. It’s all the same country, idiot. That was the conclusion of the Civil War after all. It’s been 156 years, give it up.

Shame on you. Sherman was NO hero. For example, his troops burned down mills near Roswell, GA. The young, naive and illiterate women who worked at the mills were sent 12 miles away to Marietta, GA. There the 400 young women were put on railcars and sent to Kentucky and Indiana. Then, they were abandoned. Many were unable to find jobs, return home and some had to give up their children as they could not care for them. READ the book “The women will Howl” (Mary Deborah Petite) which documents this kidnapping. The comment “The women will Howl” was a cruel and insensitive remark made by Sherman. His troops also burned down hundreds of homes, churches, businesses, schools, and stole silver, jewelry and anything of value. They destroyed crops and stole livestock. They threw dead animals into wells, so as to cause death or illness to others who drank the water. I’m sure Sherman is playing scrabble with Lucifer.

He freed tens of thousand of slaved people from their horrible lives in the south from labor, rape, and or being sold away from their family’s. If that’s not a hero I don’t know what is

Just look at his photo he looked like a terrible hateful man today he would be a war criminal Grant was no different for what he and Andrew Jackson did to the Indians.

Jackson? Hero. Lee? Hero. They fought tyrrany. Meclellan? Coward. Pope? Braggart. Sheridan? Marauder. Sherman? Marauder. They fought to keep the south under yankee control, not to promote freedom and justice.

Way to go!

You should probably remove that profile picture then, nearly every Serbian American of the 1860s fought for those “rebs” you so shamelessly insult.

Sherman was a War Criminal and should have been hung. My grandmother told me stories, passed down by her mother, about having to eat rats, boiled roots, acorns and hickory nuts. She said not a squirrel or anything remained after Sherman’s men came thru. There were also stragglers that came thru, raping and robbing, afterward that were even more dangerous than the main army. Take a ride thru Georgia some day and try to find an old plantation house,, there’s a few, but most were burned.

I do believe, when Lee was in the north, he gave strict orders not to harm anything that was not a military target

The winners write the history books.

Sherman came through parts of Bryan County…farms were only the women, children and elderly stayed. Their homes and any form of shelter burned, all food destroyed or taken and anything of any value for that matter. Sherman even sent scouts out to throw the killed livestock down every water well. Old timers still speak of haunted roads were weaker people by the thousands fled and died upon in search of food and shelter. Criminal to say the least.

Frank, I called Bryan County for 21 years, so it is not unknown to me. there were some 4000+ total residents, including those away in the CSA, during those years, according to the 1860 census. I am not an authority on the census, but since the number of southern congressmen depended partly on the 2/3 of a man rule, I would say that includes slaves. There are a number of homes, still standing in Bryan County, from those days, the Mansion at Hardwick being the most impressive, how many were destroyed when much of Bryan, including the county seat at Clyde, became Camp / FT Stewart, I am not sure. It does seem to me you are expressing myth, rather than fact. Peace be with You and all of us.

War as grant said is hell, but sherman went above and beyond to make it worse than hell. Today sherman would be tryed for war crimes and rightfully so.

Sherman fought the war the way it needed to be fought.By making war so terrible it would help Southerners think twice before turning to it again as a tool of political expediency. The story of one southern woman’s experience in Georgia that was said to be typical, in losing all her fated turkeys, pigs, chickens and thousand pounds of meat in her smoke-house showed her and fellow southern citizens just how horrible war actually is.

If that’s how to fight a war, Sherman did it well, and the Nazis did it better.

Yours, Caleb.

We condem him for his actions, but he helped bring a quicker end to a war that the Confederacy started. The only rule in war is winning. Putting rules on it is like trying to put in a new ten commandements. People do what the have to do to win. And if it is demoralizing the civilian population so bed. Notice please that I said demoralize and not murder. But the USA has done eay worse since then.

The only rule in war is winning?

You, sir, are a cad, as well as a coward.

War by Sherman, if Really studied, was an outright war on civilians, whom most had no part in the war. They had no slaves. The government of the US would have you believe that Lincoln was freeing the slaves. Poppycock.

The US government sold us up the river to communist China, where most products are made by forced adult and CHILD labor.

Do your homework before opening your piehole.

really now, I’m in China but I see 0 child labor and paid labor, you idiot. know your facts before you type online, and truly open your eyes as well, they are deceived by biased news, which, all news is biased, you cannot trust anyone but yourself. so next time, don’t rely on your pathetic daily news to your sources, **** use your own brain.

Joe, if what you say were true, how is it there were so many (almost all) of those civilians, who survived his march to the see. You are correct though, in saying most had no slaves, so why were they fighting for the slave-owners, who were doing their best to avoid the carnage ? Read the debate in the GS statehouse, prior to the vote for secession. Lastly, I’ve never known anyone who was persuaded by insult. Maybe 150+ years later, it is time to end the debate and wish that the Words of the US Declaration of Independence (celebrated wonderfully in Georgia, by the way) had been meant, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created EQUAL, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain Unalienable Rights, that among these are LIFE, LIBERTY, and the PURSUIT of Happiness…” Peace to us all.

Your jutifucation of Sherman is very “ends justify the means” which is a pretty poor argument to keep Sherman up on.

Yours, Caleb.

If you’re going to view the Civil War through a modern era lens and classify Sherman as a war criminal for waging war in a manner that made the South “feel the cost of war” in order to hasten the South’s surrender, you might as well classify President Truman as a war criminal, as well, because hastening WWII’s Pacific theater war’s end and saving American lives were a couple of major motivations for his decision to drop the bomb. Just saying.

It has been argued that Truman did not use not one, but two, atomic bombs against the Japanese to save American/Allied troops’ lives, but to show the Soviet Union what the United States had in its arsenal.

The United States actions to end the war in Japan RAPIDLY were a great benefit to Japan as well as the USA. Have you ever wondered why there is a North and South Korea? The Soviets waited until the bomb was dropped to attack down the peninsula.

If they had done this with Japan you would have had at least 2 countries instead of one. Come to think of it they did take 2 relatively small islands for over 60 years. Look at the 2 Koreas, and ask which one you would rather live in. Then consider if the Soviets took 40% or so of Japan and wonder which country you would want to live in.

Even with the double bombing the Emperor’s own palace guard tried to stage a coup to keep the war going. Would this have succeeded if only Hiroshima had been bombed? Another consideration was Japan’s own Nuclear program which was hampered by getting enough fissionable U235. But there are alternatives to the explosion bomb including one that tries to poison the target via dirty radiation. Japan’s team claimed to be making great strides in 1945, and a year or so extension into the future may have made their bombs a reality, complete with the huge submarines they had produced as a delivery means.

Finally, I am very happy that my Dad did not need to join McArthur’s proposed landings. I I don’t care if the figure was 1,000,000 dead or even just 10,000 dead. You see, I was born after WW II and kind of needed him to live. Call me selfish if you want, but I am sticking to my relief.

Oh, by the way I had 2 Aunts and 5 JapaneseAmerican cousins from woman 2 Uncles courted and married after the war.

Truman *was* a war criminal.

Sure, Truman killed thousands of innocent civilians, so he’s a war criminall, too.

Yours, Caleb.

As a southern born American,taught in southern schools. Sherman has been recused a criminal in all southern teachings. Upon my own research, Sherman was ahead of his time by causing the Concederacy to want an end to war. But on the same hand he did nothing to control his men in the field from destroying targets without due orders from ranking officers. Or those officers freely and knowingly disobeying Sherman’s own directive. Turning a blind eye made him a war criminal in his own time.Truman had his own demons and should be judged by rules at that time. We should forget about justifying causes by today’s standards. Hindsight is NOT 20/20, it is written by the victor.

Britain’s “Bomber” Harris and US General Curtis LeMay…and Truman…war criminals? Dresden, Hamburg, Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki. War criminals.

As we have read so many times, history is written by the victor.

If you’re going to contemplate whether Sherman is guilty of war crimes, it should also be pointed out that he – as Commanding General of the Army – used those same methods against Plains Indians in the years following the Civil War.

Buffalo were slaughtered wholesale in order to force starving Indians onto reservations, the government violated countless treaties when mines, railroads, or settlers desired the land, and Native Americans were coerced into abandoning their language, religion, and semi-nomadic ways – all at the point of a gun.

Despite being a southerner, I have very little sympathy for the Confederacy and I think that using such tactics against the indigenous inhabitants of this land was a far worse crime than anything Sherman did during the Civil War.

Many of these posts reflect a great ignorance of history and a moral inconsistency in life. Most Americans would probably agree that “victory at all costs” is a legitimate philosophy in combat. As a former colonel and combat veteran, I can assure you that this is not how the American military fights wars. We protect civilians, despite the added risk. This philosophy is not new, but has always been part of Judeo-Christian armies from the earliest days of Western Civilization. The application of these principles depends on leadership, as Lincoln aptly demonstrated. The most destructive, brutal, and vicious generals were the ones Lincoln most quickly promoted, time and time again. (These facts are easy to research yourself.) Sherman was no exception. The plain fact is that the destruction of the South cannot be wrapped in “punishment” language, “quickly finish the war” language, or “teach a lesson” language. The Ends never justify the Means in combat, politics, or life. Any person or army that takes the war to civilians is immoral, shameful, and deserving of judicial trial and punishment for war crimes. In short, there is no moral justification for warfare against civilians… Period.

Great points. Thank you for your comment!

“I can assure you that this is not how the American military fights wars. ”

Yes it is. The civilians of Dresden, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki wave hello from the grave.

The March to the Sea involved fewer than 3000 casualties. Rebel-supporting farms burning to a crisp is not exactly something we should be shedding tears over. The South could have ended the war at any time, but they didn’t.

War is Hell.

Ends don’t justify the means!!!

To save time and space let me say that I basically agree with Rich. Comparison with the intense retaliatory bombing raids of WWII is senseless and unfair to the allied commanders. As for the Civil War, most posters seem to believe historical myths rather than historical fact. The real war criminal here was Abraham Lincoln who started an illegal and immoral war, pursued it in spite of the terrible human cost…and did indeed always support the most ruthless, brutal and destructive generals as well as abuse the U.S. Constitution at every turn. In 1864 you could have asked presidential candidate George McClellan! For Rich, though: are you aware that the incredibly criminal war against Yugoslavia waged in 1999 by “Bomber Bill” Clinton and NATO also attacked principally civilian targets? U.S. forces violated, at least for this writer, every respectable norm of human conduct. One last point. During the Civil War the distinction between civilian and soldier were clear. Today our military faces “civilians” armed to the teeth with automatic weapons and explosives, “civilians” who cut the throats of their neighbours for differences in religious beliefs. To judge conduct one must be aware of all the facts of the particular conflict under study…and not compare apples and oranges as Lisa correctly states.

I had to comment because there isn’t a “LIKE” button. You nailed it, Dave.

The NATO bombing of Serbia was certainly a war crime, and involved the USA bombing Serbia, a traditional ally of the USA. The only reason for the bombing was retribution for Srebernica.

Yup, Lincon got what he deserved in Ford’s theatre.

What Sherman did, is nothing if we compare it with what the Habsburgs did in the middle of the 19th century during the 1848-49 revolutions against the Hungarians.

They “hired” Romanian and Serbian irregulary troops, which pilleaged, murdered in the most barbaric way tens of thousands of civilians, regardless to their gender, starting with the babies and finishing with the elderly people.

For example when the Serian troops entered in the city of Zenta, they killed 3000 people, cut their heads, and put them in the center of the town in piramids.

The Romanians did even more horrible things then this, because they killed people in very barbarical and sadistic ways, trying to make the sufferance of the people they had killed to be as long as possible, causing also inimaginable horror in those who survived.

Examples:

– killed men, and put the women from the house to cook their fleash and eat from them.

– bind people on stakes, and cut their limbs, genitalias, breasts one by one, untill they died.

– put people infront of plows, and ploughed the earth until they died

– they threw the sister of the great Hungarian writer Imre Madách, and her 13 years old son, infront of faminguished pigs, which eat them alive.

– they burned tens of cities and villages to the ground (Nagyenyed, Marosújvár, Abrudbánya, Zalatna, Négyfalú, Magyarigen, etc.), massacring the Hungarian population from them.

All these cruelties were made with the knowledge of the Austrians generals and state, who ordered these massacres in order to put terror in the hearths of the Hungarians, to convince them to stop the resistance against the Habsburg empire. And this was not one mans policy but the empires state policy.

Similar cruelties were made with the order of the Habsburgs in Transylvania in 1783-84 by the Romanians against the Hungarians, or in 1846 by the Ukrainian peasants against the Polish revolutionaries in Galicia.

I have no sympathy for the rebel households that Sherman looted, burned, or pillaged. The civilian population supported the cause of the traitors.

And the notion that “modern warfare” invented the damage to civilians is simply the stupidest and most ignorant thing that I have read re the Civil War. Since time immemorial, war has been visited upon the civilian population. A sack of a town during the pre-modern era would result in the deaths of all the men, the rape of all women between the ages of 10 and 70, and the enslavement of able-bodied adults. Children would be killed.

In every age, in every war, in every country, civilians were involved, killed, and raped. The modern war notion of “civilized” warfare is new since 1945. It’s mostly not observed, and USA troops are just as likely to commit atrocities as those of other countries.

There’s nothing “new” about what Sherman did. For reference, look into what the English routinely did during the 100 years war. The exact same things Sherman did (for the same reasons) were called the “chevauchee”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chevauch%C3%A9e

Thanks for posting, that is useful context.

The preamble of the Declaration of Independence written July 2, 1776. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that ALL MEN ARE CREATED EQUAL, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness”. The three-fifths clause (Article I, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution of 1787) in fact declared that for purposes of representation in Congress, enslaved blacks in a state would be counted as three-fifths of the number of white inhabitants of that state. The most notable other clauses prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territories and ended U.S. participation in the international slave trade in 1807. These compromises reflected Virginia Constitutional Convention delegate and future U.S. President James Madison’s observation that “…the States were divided into different interests, not by their…size…but principally from their having or not having slaves.

So the issue of ownership of another human being was a root cause of the Southern state’s succession from the Union.

Abraham Lincoln explained his objections to the Kansas-Nebraska Act 1854. In the speech, Lincoln criticized popular sovereignty. Questioned how popular sovereignty( this could allow slavery above the Missouri Compromise line) as it could supersede the Northwest Ordinance and the Missouri Compromise. Lincoln dismissed arguments that climate and geography would keep slavery out of Kansas and Nebraska. Most importantly, Lincoln attacked the morality of slavery itself. Lincoln argued that the slaves were people, not animals, and consequently possessed certain natural rights.

Lincoln’s Letter to Horace Greeley NY Tribune wrote “I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause 1862

In the Gettysburg address he said Four score and seven years ago,” referring to the signing of the Declaration of Independence 87 years earlier, Lincoln described the US as a nation “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” and represented the Civil War as a test that would determine whether such a nation, the Union sundered by the secession crisis, could endure 1863

Seven southern states seceded from the Union rather than continue to negotiate and compromise over the issue of slavery, which had been the norm for so many decades. The first state to secede was South Carolina on December 20, 1860. By February 1861, six more states had joined the new Confederate States of America.

Abraham Lincoln becomes the 16th president of the United States on March 4, 1861. In his inauguration speech, Lincoln extended an olive branch to the South, but also made it clear that he intended to enforce federal laws in the states that seceded

Convinced that their way of life, based on slavery, was irretrievably threatened by the election of Pres. Abraham Lincoln (November 1860), the seven states of the Deep South (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas) seceded from the Union during the following months. When the war began with the firing on Fort Sumter (April 12, 1861), they were joined by four states of the upper South (Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia).

On September 17, 1862, Lee planned to achieve some of his thwarted objectives from the Maryland Campaign through a cavalry raid. He asked Major General J.E.B. Stuart to lead the raid. Stuart took 1,800 men and a four-cannon light artillery battery on the raid. Stuart crossed into Maryland west of the Army of the Potomac’s encampments, raided Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania

So JEB Stuart under the orders of RE Lee raided northern cities in Pennsylvania in 1862 and burned some of them to the ground. There were other raids on northern cities.

Wm T Sherman’s march through Georgia did not happen until more than 2 years later.

Now From November 15 until December 21, 1864, Union General William T. Sherman led some 60,000 soldiers on a 285-mile march from Atlanta to Savannah, Georgia. The purpose of Sherman’s March to the Sea was to frighten Georgia’s civilian population into abandoning the Confederate cause.

By the time the war ended 750 k had died. Some would like to label Sherman as a war criminal however there were questions of atrocities on both sides and the treatment of the POW’s could fall into potential war crimes

There were plans for a prisoner exchange however the Confederate states voted not to exchange black soldiers so the number in POWs grew. They were treated less than human.

In December 1862, President Davis responded by issuing a proclamation that neither captured black soldiers nor their white officers would be subject to exchange. In January 1863 the Emancipation Proclamation became official and the United States began the active recruitment of black soldiers. The Lieber Codes, also known as General Order 100, was issued in April 1863 and stipulated that the United States government expected all prisoners to be treated equally, regardless of color. In May of 1863, the Confederate Congress passed a joint resolution that formalized Davis’ proclamation that black soldiers taken prisoner would not be exchanged. Many of these soldiers both white and black were summarily executed no trail just shot this occurred before Sherman’s march.

So Total War is not a new concept the Israles committed it against their enemies, Alexander the Great, Atilla the Hun, Vikings, Gehangis Kahan and many others have been brutal in their attack on civilian populations trying to bring a people under their control.

If a state executes an act of war against a nation who they have sworn allegiance to is that not considered treason, the first shoot of the Civil war was fired at Ft Sumter in SC. I would ask how brutal were the negro’s treated by their southern masters, I am sure their living conditions were poor at best and it was against the law for them to learn to read or write? I do not have any sympathy for any person or state who takes up arms against the United States. I also do not have sympathy for people who think or believe because of the color of their skin they are superior to them; it’s racist and it’s immoral.

John Rodgers USA Ret.- You are reading noting but revisionist history books I see, I use the term “hIstory” loosely. So many of your claims are pure specious crap my friend. The Union initiated the NO EXCHANGE policy, This for the sole reason that it further strained the South’s limited resources, We are talking about the CW & not Gengis Khan, etc, etc, My lord man, Wake up, Mass executions of prisoners…Smh! Reference?????? I could go on & on but it would make no difference in your misguided beliefs about CW history.

John Rodgers- You are on Mars, References on the execution of prisoners claim??? You need to read some HISTORY, Not Revisionist either.

Sherman was a moral coward, a genocidal maniac and, of course, a war criminal. This article fails to set Sherman’s crimes into the overall context that Lincoln’s provocation and prosecution of the war against Americans was the blackest crime and that Stanton, Seward, Grant, etc all played their role in perpetrating it.

The Southern States seceded lawfully and in accordance with the Constitution. Lincoln committed the first criminal act by refusing to respect their decision. The Founders established a confederate republic of sovereign States – not the unitary empire of Abraham Lincoln. The US was not a political “Hotel California” – where you can check out any time, but you can never leave.

“During Sherman’s stay in Columbia, South Carolina, one black woman, a servant of Episcopal minister Peter Shand, was raped by seven soldiers of the United States army. She then had her face forced down into a shallow ditch, and was held there until she drowned. William Gilmore Simms reported how “Regiments, in successive relays,” committed gang rape in Columbia on scores of slave women.”

In addition, Sherman’s men desecrated graves, plundered food and left women and children to starve, burned churches and threatened to throw the protesting pastors into the flames, tortured elderly men to try an locate family silver to steal, and scores of other outrages.

The fact that acts of cruelty had been perpetrated before in Europe is beside the point. They were also crimes. Western Christendom, since medieval times, does not sanction making war on non-combatants. What Sherman (and many other yankees) did during the WBTS was unprecedented in American history and set us down the road to greater atrocities in the 20th century. The author apparently fails to see the irony in his closing:

“Rejecting what Sherman did requires the rethinking most of the United State’s wars in the 20th century.”

The moral gymnastics required for exculpatory arguments whitewashing or minimizing Lincoln’s war in general or Sherman’s acts in particular become so convoluted that we have to send 20th century atrocities back in time in order to provide relief and context. Much of what the US did in the 20th century – particularly the bombing of civilians in WWII – was immoral and dishonorable and Sherman started the US on that path to hell.

I think you may have misunderstood my intention in the article a bit. My opinion is that both Sherman’s march and the American war attacks on civilians in the 20th and 21st centuries were morally wrong. Thanks for reading.

As a mere Brit happening upon this article in your excellent history Website, and having just re-read Gore Vidal’s impressive and provocative study of the Union’s great – but troubling – President, in the novel ‘Lincoln’, I do think that (to use an Americanism long ‘borrowed’ by us Brits) ‘the buck stops’ with Lincoln where the manner of the prosecution of the war against the Secession States is concerned.

This is the besetting sin of all power: that occasions will arise when that power will be used ruthlessly, since however reluctantly or righteously embarked upon, war and it’s paroxysmal and blind rage is the ultimate resort when civil compromise breaks down. War is that periodic collapse of civilisation ever attendant upon the moral defect that lies in mankind since the Fall. At least it can surely be said that Lincoln – as well as each of those later American Presidents faced with their own terrible dilemmas – was fully aware of and agonised by (as Vidal portrays him) the tragedy that overtook his young country and nation.

Napoleon possessed a kindred sense of his own fallibility, and the tragic tendency in great undertakings. Both were enlightenment figures, and each retained a decent degree of humanity throughout their extraordinary careers. With all their sins upon them, I do not think that the likes of such men contemplated – as savages like Hitler certainly did – the use of terror, torture and murder as the norm of their vision for humanity: Napoleon wished an end to the increasingly arbitrary horrors of the Revolutionary Terror in France, and Lincoln wished an end of the complacent inhumanity that was enriching the southern states with the systematic and unchecked degradation of enslaved human beings: Both these remarkable careers sprang from a disgust with certain moral excesses.

Hitler was of the Satanic school that cynically declared (in Milton’s words) ‘Evil, be thou my Good.’ Such a rule would mean eternal degradation for all humanity for all time. Napoleon’s political and administrative innovations still influence enlightened modern European systems of government; and, had Lincoln not been assassinated by a rogue Southerner, I believe that his conscience would have ensured that the South enjoyed that complete, generous and restorative Reconstruction which he always, with great magnanimity, intended, and which, with his premature demise, the lack of keeps open those wounds that trouble Dixie to this day. On the other hand, Hitler’s nightmare vision of a ‘Thousand Year Reich’ would have been ‘a boot stamping on a human face – forever’, as Orwell characterised dictatorship.

I believe that both Napoleon and Lincoln were very capable of tormenting their own consciences during their own lives, whereas Hitler was simply a psychotic and inhuman mass-murderer whose entire mission of irrational hatred was to create mayhem, terror and destruction, unamenable to mercy, magnanimity, amelioration or amends. By contrast, Napoleon and Lincoln were stirring examples of humanity writ large – their sins magnified, and terrible enough indeed, yet redeemed by a true greatness that was morally epic, and whose respective legacies were, above all, measured in worthwhile achievements.

Lumping such figures in with the category of monster for whom destruction is an end in itself is morally indefensible. Surely we can admit that the ordinary imperfections and fallibility of humanity must be accepted as the only soil out of which any goodness can spring? All action on the grand scale is a gamble, and will inevitably prove disastrous in some part. But only complacent and self-righteous mediocrities can see themselves as superior to such great men as Lincoln, since they have never been tested in the crucible of history.

To see such pipsqueaks sniping at a monumental figure like Lincoln reveals them to have the wretchedly mean soul of a John Wilkes Booth – a creature whom the great Confederate General Robert E. Lee utterly repudiated!

(I hope this insignificant Brit may be indulged in airing thus his opinion of such a sacred American topic as the foundation of your great country.)

Having read all the comments to date, one can recognize and validate several assumptions the readers have made. Few are based on truth. Many are based on emotions. This immediatley disqualifies them, not of being factual, but of being rational.

The civil war was not fought over slavery. It was fought over states rights, only one of which was slavery.

To some, Sherman will always be a war criminal. To some, he will be a hero that helped end the bloodiest war we have been in. A few facts can go a long way in diffusing emotional responses on both sides of the argument. Sherman did in fact out run his supply trains. I have heard many argue that this alone didn’t have a large impact. In fact, it had a giant impact on his army. Imagine a modern football stadium full of people, and you have just been told that you have to feed all of them. Not for the day, but for the month. Then you find out that you will only be able to move them about five miles a day. Then through in the account of the theft of 18 turkeys and a thousand pounds of meat. Divide by 60,000. Do the math and let me know how full you would feel. And that is only for one day.

A another overlooked fact is that it a 60,000 man army, there are probably a dozen layers of management, from squad leaders up to brigade commanders, and finally Sherman, then the President. After the Mei lay war crime during the Veit Nam war, The man that was held accountable wasn’t General Westmorland, bet a lowly commander named Lt. Calley. Is it realistic to think General Sherman was notified every time a private stole a pig? But he sure heard about every private being to weak from hunger to fight.

There has never been a pretty war. Even the holy wars had very bad things happen in them. And usually only one side thinks it is holy. If mankind could have learned from the bad things in war, you would think we could learn not to have wars.

You would think.

Jackson hanged soldiers for theft. If Sherman did that, then he wouldn’t have had such a hard time to control his men.

I would be so very interested to hear your assessment if similar tactics were being ordered by Command to be employed today by US troops, ravaging through a middle eastern country today – raping, murdering, and kidnapping unarmed women and children non-combatants and plundering and pillaging their possessions. I wonder if you would call it war crimes then?

Don’t you dare try to defend it as “the times”, as raping and murdering women and children was as immoral and criminal in 1865 as it is today. The fact that yankees stoutly defend this madness is partially why there still exists to this very day, such animosity between the citizens of the north and the South.

Yes of course I would. Furthermore, I believe war crimes have been committed by the US government and/or US troops in the Middle East in recent times.

I hope some day that William Sherman’s remains be removed from their holy grounds to a secular cemetery site.

Any sentiment how deep can never out weigh the horrific atrocities he commited.

Sherman neither invented, nor practiced, total war during the Civil War.

Sherman wasn’t mass murdering or bombing civilians in the 1860s, but military history is replete with the mass murder, torture and enslavement of civilians.

And if you really want to see some real examples of “total war,” then look at the U.S. bombing of civilians in WWII, BEFORE, during and after Hiroshima. And the massacres, bombing and napalming of civilians, including women, elderly and children of course, during the Vietnam War.

And as for the Civil War, the South admittedly explicitly and intentionally started the war to perpetuate the enslavement ( including murder, torture, rape, mutilation etc) of millions of human beings, and committed the mass murder of Union soldiers and massive destruction of property, while making refugees of American civilians.

Sherman didn’t start the war; He ended it. And he ended it quickly, saving countless lives. (As any war historian knows, more soldiers were dying from disease than bullets. And Sherman was aware of the suffering of the POWs in Andersonville.)

And Sherman had warned Southern leaders against starting the war, and very accurately predicted exactly what would happen if they did. But they stupidly started it anyway.

Those who single out Sherman to condemn are giving the entire world history of war criminals a pass, and are being willfully oblivious to all the atrocities of the Confederacy provoking the inevitable necessary Union response.

Sherman wasn’t a war criminal. Full Stop. Andersonville was a war crime. The Confederate Politicians who voted to secede are war criminals.

Sherman deserves better than you weak willed wannabe armchair generals on this sad excuse for a white supremacist site. Long Live the Union and Thank God for John Brown.

Calling us a “white supremacist site” is a pretty disgusting accusation, can you give one example of a white supremacist post on this site?

Andersonville wasn’t done as well as it could have been, but the south didn’t have the resorces to properly run a POW camp. Show me where the constitution says that you can’t secede. John Brown murdered, looted, and stirred up trouble. Do you know why he got caught? He heard about a famous sword in a nearby house. He thought that it would look good on him, and he was so vain that he decided to go get it instead of leaving Harper’s Ferry. So he got the sword, but it was too late to escape.

Yours, Caleb.

Of course Sherman was a war criminal, and so was Abraham Lincoln and those US commanders and servicemen who ordered and carried out attacks on civilians in WWII. Sherman did not need to wage a war against civilians in order to end the war. All that was needed was for the North to withdraw and recognize the independence of the CSA. Even if he did it would not be sufficient justification in targeting civilians and their property. This sort of “total war” military conduct is not in accord with Christian principles. Only Godless utilitarian calculations can justify such barbarity.

Way to go, feller!

US Troops Could be Committing war crimes But if you look at the Opposing side you would see that war crimes committed by the US army(Among Other Branches) Would Look minor as the Majority of Terrorist organizations commit war crimes (Damage to Civilian Held Land/Targeting Innocent People) While the Claim that “THE TIMES” Would not make sense as if you look at The Yugoslav Wars you would see that was Modern and that was Not “THE TIMES”. The Claim that Sherman would not know if a Private stole something is a stupid Idea that Sherman would not have Pushiments laid out. The excuse that Sherman would not have “time” or was too “hard” to Punish Soldiers that stole is stupid. The fact that Sherman would not tell lower ranking officers to punish soldiers if they do this is stupid as they are responsible for the conduct of their soldiers as they are their Officers.

Today Sherman would be a war criminal and Grant and Andrew Jackson the same for what they did to the Indians.

I don’t see ww2 as an excuse for Sherman’s crimes. Bombing civilians is wrong. Raping and arson are wrong. I was always taught that 2 wrongs don’t make a right.

One could make the argument that these actions hastened the end of conflict, and could thus be justified, but they are still immoral.

Way to go!

P.S. I like your profile image.

Good post.

in answer to the question was Sherman a war criminal, I would posit the following. During the Veit Nam war a young Lt Calley used the same tactics as Sherman, lost control of his men JUST LIKE SHERMAN, and was tried and convicted of war crimes by The United States Government. Sherman fought not one war in that manner, but two. The civil war and the Indian wars.

I think the case of Lt Calley and the My Lai Massacre is quite a bit different than that of Sherman’s Civil War campaigns. There were no incidents that I’m aware of where Sherman’s men massacred hundreds of civilians. Though a judge did reference Sherman’s “War is hell” comment in his decision ordering Calley’s release.