It was spring of 1817. Two young missionaries stood on the deck of a ship, peering into the distance toward the new and strange land where they would spend their lives. A long line of white sand greeted their eyes, a refreshing break from the brilliant blue skies and water they had seen for weeks. John Williams and his wife, Mary, had left behind the comforts and pleasures of home to come and give their lives to the service of the Master in the islands of the South Seas. These islands had only recently come to the attention of Western Europe. Psalm 97:1 says, “The LORD reigneth; let the earth rejoice; let the multitude of isles be glad thereof.” Until the voyages of Captain James Cook in the 1770s, the islands of the South Pacific were bound in darkness.

The 30,000 islands of the Pacific present a daunting task to the missionary. Over a third of the world’s known languages exists in these islands. Fifteen million people live across a vast expanse of ocean that stretches over twenty million square miles of water. The tropical beauty of the surroundings contrast sharply with the ugliness of sin. Infanticide was a common practice. Cannibalistic feasts were part of the superstitious religion of these islands. People worshiped everything from demons to birds to ancestors to stone idols, and religion, customs, and language vary widely from island to island.

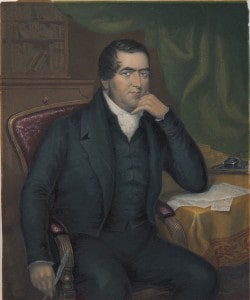

These islands captured the heart of Welsh missionary John Williams, later to be known to history as the “Martyr of Polynesia.” More than any other man, John Williams would be the instrument of God to open the islands of the South Pacific to mission work. The first island upon which the Williams labored was the beautiful island of Tahiti, in what is now French Polynesia. It was there that a small mission work had already been founded, and Williams and his wife learned how to operate a mission station among cannibals.

The first island where Williams began a pioneer work was the island of Raiatea in the Society island group. There, John and Mary Williams were welcomed cordially by King Tamatoa, a monarch who had been looking for someone to come and give them the message of salvation. The Williams served on Raiatea for about five years. In this short period of time, they saw remarkable results they could not have imagined. Their congregation was regularly in excess of 2,000 people. Hundreds were baptized and began to live as consistent Christians. Naked cannibals learned to put on clothing. All the wooden idols on the island were collected and burned. Stone idols were sunk into the sea. Houses were built. Farms were cultivated. Animals like goats, horses, and cattle were brought from Australia. The natives were astonished by these animals. Goats they called “birds with great teeth in their heads.” Horses were known as “great pigs that carry men.” Soon these animals were put to productive labor. King Tamatoa prospered as he ruled in the fear of God, using the law code given on Mount Sinai. John Williams reduced the native language to writing and translated the Bible into Raiatean. Soon, the work was ready to be entrusted to native workers. Williams wrote back to his parents in Wales, “I am engaged in the best of services, for the best of masters, and upon the best of terms.”

John Williams next turned his attention to an island in the Cook group, the island of Raratonga. Here he experienced similar success. It should be noted, however, that the mission work was not without its troubles. Several times, there were violent plots upon his life. Malaria and other tropical diseases took their toll on the Williams family. Mary Williams lost several babies, and they were buried in neat graves of rock and coral, monuments to the sacrifice of a missionary family. After Raratonga was thoroughly evangelized and the triumph of the Gospel was assured, John Williams turned his attention again eastward, toward the Samoan group. It was during these years that he planned the evangelization of the South Pacific. He knew that white men alone could not do the work. Native teachers who understood the culture, knew the languages, and were familiar with the seas were an important part of a missionary endeavor.

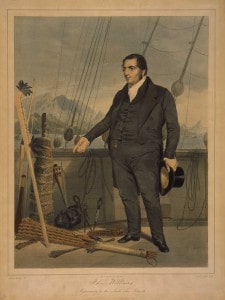

Williams took his example from the Lord Jesus who sent out his disciples two by two to preach and teach in the rural villages of Galilee. The Apostle Paul also used native workers like Aristarchus and Tychicus to evangelize the villages with the Gospel. Following this pattern, Williams commissioned a ship to be built that would serve as a mobile base of operations. The ship was called The Messenger of Peace. As the missionary team sailed, Williams would stop on various islands and meet with the chiefs. If the chiefs were willing, Williams would leave native teachers from Tahiti, from Raiatea, or from Raratonga to serve in the pioneer stations. Islands like Aitutaki, Upolu, Apia, Savai’i, Futuna, and many other smaller islands were reached in this way over a period of about ten years. Native workers multiplied the efforts of Williams, and the work prospered. Like the Apostle Paul, Williams would return in The Messenger of Peace and “visit the churches to see how they do” (Acts 13:36). It was this Biblical policy that brought the islands of the Pacific under the triumphant reign of Christ. Williams set a pattern that other missionaries like John G. Paton would later follow in the New Hebrides.

In 1833, John and Mary Williams revisited England for the first and only time. Mr. Williams was surprised to find himself a hero. Vast crowds thronged into the churches to hear him preach and tell eager-eyed boys and girls about the needy cannibals of the South Pacific. Purses were opened to the cause. Young men and women resolved that, by God’s grace, they would become pioneer missionaries also. Williams wrote a short description of the South Sea islands, and 38,000 copies sold within five short years. While in England, John and Mary Williams celebrated their 20th anniversary—and almost their last. He wrote this note for her to find on that anniversary morning,

My Dearest Mary, Twenty eventful years have rolled away since we were united in the closest and dearest earthly bond, during which time we have circumnavigated the globe . . . I sincerely pray that, if we are spared twenty years longer, the retrospect will afford equal or even greater cause for grateful satisfaction.

On April 11, 1838, John and Mary Williams set sail from London, bound for the other side of the world. The wharves, docks, and bridges were lined with people who came to see them off. Mortality was so high in the South Pacific that they made the difficult decision to leave their six-year-old son in England. As the ship pulled away, a kind relative lifted Samuel high into the air so his parents could see him in the crowd. The eyes of the little boy streamed with tears, but he was old enough to know that his Mommy and Daddy were going back to his dark-skinned friends to give them the Gospel. That morning, his loving father had written a note in Samuel’s journal, giving him a warm goodbye and a fatherly exhortation to live for Christ if perchance they never met again in this life.

The Lord bless thee, my dear boy, and keep thee; The Lord make his face to shine upon thee and be gracious unto thee; The Lord lift up his countenance upon thee and give thee peace.

Only one year later, soon after he had arrived back in the South Pacific, John Williams set his sights upon the New Hebrides islands. It was known that the inhabitants of these islands were among the fiercest cannibals in the Pacific. Leaving his wife at the mission station on Upolu, Williams sailed toward the New Hebrides.

In the morning of November 20, 1839, John Williams prepared to land on the island of Erromango. In his Bible was later found a small scrap of paper upon which he had written this text from the lips of the Lord Jesus, “I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail not.” This petition was gloriously answered on that bloody day, and the faith of John Williams did not fail. He was brutally beaten with a war club, and his corpse was dragged into the dense vegetation to be cooked and eaten. The grief-stricken native workers, the faithful fellow-laborers of John Williams, watched the entire ordeal from the boat. They were the ones who had to tell Mrs. Williams the sad news. She took it with grace and Christian fortitude. Her eldest son, John, continued his father’s work in Samoa. Samuel, the little boy left in England, also became a messenger of the Prince of Peace. He carried the middle name, Tamatoa, the name of the Island King who first welcomed his father to Raiatea.

John G. Paton, the son of a Scottish stocking-maker would follow the noble example of John Williams twenty years later. John G. Paton and his wife determined to labor in the New Hebrides islands to finish the work that John Williams had so nobly begun. By God’s grace, their effort was grandly successful. The islands of the New Hebrides, now called Vanuatu, fulfilled the glorious promises of Psalm 97, and the tongues of former cannibals and their descendants still sing the praises of the Redeemer.

Bibliography

John Williams, The Martyr Missionary of Polynesia by James Ellis

The Autobiography of John G. Paton

He is in heaven.. You ?

yes

This article sounds pretty biased against native Pacific Islanders. The use of the term “savage” is pretty connotative (if you ask me) and the missionaries are made out to be heroes who accomplished clothing the naked. I’m sure they’ve done some good, but I wouldn’t write an article like this that makes out these white, European missionaries to be heroes and saviors to the people of the Pacific. Because they weren’t.

@ LOUISA

There is only one savior, and anyone who believes in him, knows he is the only way and would not pretend otherwise. Jesus commands us to take the gospel throughout the world…the great commission. I don’t think the article claims these missionaries to be heroes, but it does show how much they were willing to SACRIFICE to follow Jesus’ commands. What some of these missionaries did would hardly be conceivable for so many of us today. I did not detect any malicious intent in the article to depict the islanders in any other fashion than what was directly written. “Savages”? I did not see that particular word used in the article. I did see the word “cannibals”. However, I would say that if a particular person, or people group, made it a habit to kill humans for the purpose of eating, then dare I say they deserve the label as a savage?

No malicious intent came from my fingers when they typed the words above. For I am wretch, a sinner, saved by grace and I have no right to condemn.

Blind worship in anything is pure mind poison, be it organized religion, stone gods, rituals and so on.

While a great tale, there is a strong aftertaste of whitewash after reading it.

Great article! What a life given Wholly to Jesus Christ. I admire this man. Thank you for reminding us of John William’s great love and sacrifice for the people of the Pacific Islands.

Reading from Mombasa, Kenya 🖐🏿

It was not John Williams son who brought Christianity to Samoa. It was John Williams in 1830 before He was killed by the Erramangos. His cartilages are buried in Samoa.God Bless….

Reading from Samoa🙏