On his return to England, Shackleton was in high demand and the first of the explorers to come home. He assisted the Admiralty in the preparations of a relief ship for Scott, and was offered the command. Surprisingly, he turned down the offer. Although the chance to return to Scott as his rescuer, instead of an invalid must have been tempting, he had other things on his mind.

On April 9, 1904 he married Emily Dorman, who he had known for years. They would have three children. Ernest Shackleton would prove to be a bad husband. His lack of patience, a character fault throughout his life, would demonstrate itself here. He had many affairs, and preferred to travel the world rather than stay at home to be a husband and father.

Shackleton failed to gain lasting fame from the Discovery expedition, so he turned to other ways of gaining fame and fortune. He was impetuous and lacked patience. He wanted to get rich quick, without having to devote himself to a profession. He was, however, very persuasive and charismatic and could often pull people into his schemes. He was very similar to his brother Frank Shackleton. Frank, like Ernest, was very persuasive, and had a drive to rise in society. He was a homosexual, and strove to live by his wits in high society. But, like his brother, he was bad with money. He tried many schemes, which all proved to be failures. On July 6, 1907 it was found that the Irish Crown Jewels were missing. Frank Shackleton was a prime suspect. Although enough evidence was never found to convict Frank, he later went bankrupt, was charged with several crimes, and died in poverty under an assumed name. Ernest was a similar man in many ways, and he may have turned out the same if he had not devoted himself to Antarctica.

Ernest Shackleton went through many jobs in a short time, working at a newspaper, being elected the Secretary to the Royal Geographic Society, and forming a company to transport troops to Russia. He was found to be a good public speaker, and ran for Parliament in the election of 1906, only to be defeated with the rest of his party. Unsuccessful in his business dealings and with his finances in disarray, Shackleton decided to go back to Antarctica. As one of his friends at the Geographic Society said, “He cannot settle to sedentary work but is splendid at bustling around!”1

Nimrod Expedition

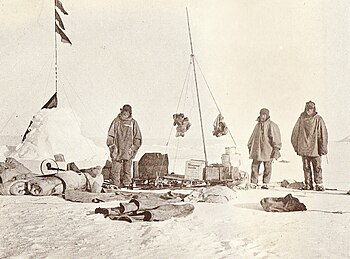

Shackleton worked hard to raise money from his wealthy friends and was eventually successful – but just barely. He set off in the small ship, the Nimrod, leaving New Zealand on January 1, 1908. Shackleton’s original plan had been to use the old Discovery quarters in McMurdo Sound, but had been persuaded to promise to find another, as Scott was thinking of making another expedition and claimed a right to his old quarters. However, when Shackleton reached the inlet in the great Barrier where he planned to make his camp, he found that that section of the ice had collapsed, and had been replaced by a huge bay. He decided it was too dangerous to camp on the ice, and with the season drawing to a close and the looming prospect of being frozen in, he decided to break his promise and camp near the Discovery quarters.

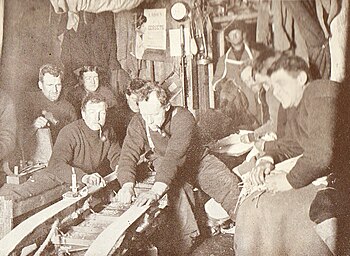

After landing supplies, a party of men, not including Shackleton, made the first ascent of the nearby volcano Mount Erebus. Throughout the long, discouraging winter, Shackleton was successful in maintaining his men’s high spirits. He was what Scott was not, a natural leader. Most of the men loved him and would follow him to the end of the world.

Great Southern Journey

On October 19, 1908 Shackleton set off on the Great Southern Journey toward the South Pole, accompanied by Frank Wild, Eric Marshall and Jameson Adams. Although he had fixed some of the mistakes that Scott had made, such keeping the men at the hut supplied with fresh meat to prevent scurvy, he still repeated some of the same mistakes. He brought ponies instead of dogs, because of the experience of the Discovery expedition. If he had talked to other explorers, like the Norwegians, he could have learned how well dogs could perform under the right drivers.

The four men encountered great hardships on their journey. The ponies were a failure. They were not suited as dogs were to the cold temperatures and icy surface. However, on November 26 the men passed Scott’s Furthest South, having covered the same distance in a much shorter time. The Barrier surface became more broken, and they encountered a range of high mountains rising out of the ice. They discovered and named Beardmore Glacier, and with a difficult climb, made it up the glacier onto the Polar Plateau. There were tensions between the explorers, with Frank Wild thinking that Marshall and Adams did no work at all, but Shackleton was at his best in a crisis. He remained calm, patient and cheerful. They came very close, within 97 miles of the Pole. But Shackleton knew he had to turn back. The way had been cleared for the next explorer. Doubtless Shackleton could have made it, but they would have died on the return journey, as Scott did on his next expedition. It took more courage of Shackleton to turn back nearly within sight of the pole, what had been his goal for so long. But as Shackleton told his wife, “a live donkey is better than a dead lion.”2

Although they had turned back in time, the return journey was still very difficult. The ponies long dead, they were man-hauling the sleds on half rations. They barely made the supply depots without starving. Shackleton was very sick, but as Adams said, “the worse he felt, the harder he pulled.”3 On January 31, Shackleton gave his morning biscuit to Wild, a gesture which meant much while nearly starving in such conditions. Wild wrote, “BY GOD I shall never forget. Thousands of pounds would not have bought that one biscuit.” Arriving back on the Barrier they made good time, helped along by a sail attached to the sled. However, 38 miles from their camp, they encountered a blizzard which confined them to the tent. Shackleton knew he had to hurry, because the ship was set to leave Antarctica on March 1, so setting off with only Wild, they marched as fast as they could. Desperate to attract the attention of the ship before it left, they even set fire to a wooden hut to make sure they reached the ship in time. When they finally arrived and set eyes on the Nimrod, Wild recorded “no happier sight ever met the eyes of man.” Soon Marshall and Adams were rescued, and the expedition set off north on their return journey to England.

Although he had not been successful in reaching the pole, Shackleton was heralded as a hero on his arrival to England. Roald Amundsen, a great explorer himself, said, “Sir Ernest Shackleton’s name will always be written in the annals of Antarctic exploration in letters of fire.” He was knighted by the king, and given a medal by the Royal Geographic Society. He was a celebrity in high demand, and had a constant round of dinners, speaking engagements and parties to attend. He did not, however, receive large financial benefits. His finances were in disarray, as usual, and he still owed much money for the Nimrod expedition. He was saved for the time by a 20,000 pound grant from the government, but still neglected to pay the salaries of many of the crew. He again tried many schemes to gain quick riches, but they all failed, and he went on rounds of lecture tours to pay his family’s expenses.